Venice-based graffiti artist Manuel Di Rita, known as Peeta, created this eye-fooling mural in Mannheim in 2019.

Venice-based graffiti artist Manuel Di Rita, known as Peeta, created this eye-fooling mural in Mannheim in 2019.

philobiblist

n. a lover of books

Created by Slovakian artist Matej Kren, the Idiom Installation in Prague’s municipal library seems to present an infinite tower of books, thanks to some conveniently placed mirrors.

It debuted at the São Paulo International Biennial in 1995 and moved permanently Prague in 1998.

Before the 19th century, containers did not come in standard sizes, and students in the 1400s were taught to “gauge” their capacity as part of their standard mathematical education:

There is a barrel, each of its ends being 2 bracci in diameter; the diameter at its bung is 2 1/4 bracci and halfway between bung and end it is 2 2/9 bracci. The barrel is 2 bracci long. What is its cubic measure?

This is like a pair of truncated cones. Square the diameter at the ends: 2 × 2 = 4. Then square the median diameter 2 2/9 × 2 2/9 = 4 76/81. Add them together: 8 76/81. Multiply 2 × 2 2/9 = 4 4/9. Add this to 8 76/81 = 13 31/81. Divide by 3 = 4 112/243 … Now square 2 1/4 = 2 1/4 × 2 1/4 = 5 1/16. Add it to the square of the median diameter: 5 5/16 + 4 76/81 = 10 1/129. Multiply 2 2/9 × 2 1/4 = 5. Add this to the previous sum: 15 1/129. Divide by 3: 5 1/3888. Add it to the first result: 4 112/243 + 5 1/3888 = 9 1792/3888. Multiply this by 11 and then divide by 14 [i.e. multiply by π/4]: the final result is 7 23600/54432. This is the cubic measure of the barrel.

Interestingly, this practice informed the art of the time — this exercise is from a mathematical handbook for merchants by Piero della Francesca, the Renaissance painter. Because many artists had attended the same lay schools as business people, they could invoke the same mathematical training in their work, and visual references that recalled these skills became a way to appeal to an educated audience. “The literate public had these same geometrical skills to look at pictures with,” writes art historian Michael Baxandall. “It was a medium in which they were equipped to make discriminations, and the painters knew this.”

(Michael Baxandall, Painting and Experience in Fifteenth Century Italy, 1988.)

04/10/2021 UPDATE: A reader suggests that there’s a typo in the original reference here. If 9 1792/3888 is changed to 9 1793/3888, the final result is 7 23611/54432, which is exactly the result obtained by integration using the approximation π = 22/7. (Thanks, Mariano.)

Thomas Heatherwick designed this “rolling bridge” in 2002 as part of a redevelopment of London’s Paddington Basin. When not in use it curls into an octagon half the width of the waterway, and when extended the eight sections form a 12-meter footbridge.

It won the 2005 British Structural Steel Design Award in 2005.

Only one castrato made solo recordings — Alessandro Moreschi performed for the Gramophone & Typewriter Company in 1902 and 1904, when he was in his mid-40s. For 30 years he had sung as first soprano in the Sistine Chapel Choir, but in 1903 Pius X ordered that the remaining castrati be replaced by boys. He died in 1922 and lies in Rome.

The scores of George Crumb’s Makrokosmos piano suite take unusual forms: a circle, a cross, a spiral, a peace sign.

Each is handwritten.

In 1924 architect Frederick Kiesler proposed a house fashioned as a continuous shell rather than an assembly of columns and beams:

The house is not a dome, but an enclosure which rises along the floor uninterrupted into walls and ceilings. Thus the safety of the house does not depend on underground footings but on a strict coordination of all enclosures of the house into one structural unit. Even the window areas are not standardized in size or shape, but are, rather, large and varied in their transparency and translucency, and form part of the continuous flow of the shell.

Storage space is provided between double shells in the walls, radiant heating is built into the floor, and there are no separate bathrooms, as bathing is done in the individual living quarters.

“While the concept of the house does not advocate a ‘return to nature’, it certainly does encourage a more natural way of living, and a greater independence from our constantly increasing automative way of life.”

(Via Ulrich Conrads, The Architecture of Fantasy: Utopian Building and Planning in Modern Times, 1962.)

The Blackbird is a full-size playable stone violin crafted by Swedish sculptor Lars Widenfalk. The instrument incorporates diabase from his grandfather’s tombstone, with a backplate of porphyritic diabase, both materials more than a billion years old. The design is based on drawings by Stradivarius, but Widenfalk made some modifications to allow it to be played.

The fingerboard, pegs, tailpiece, and chinrest are of black ebony, and the bridge is of mammoth ivory. “What drove me on was the desire to discover the limits to which this stone can be pushed as an artistic material,” Widenfalk said. “At two kilos it is heavier than wooden violins, but it gives you the feel that you are carrying Mother Earth.”

In 1776, draftsman Filippo Morghen produced a set of 10 etchings with a startling title: The Suite of the Most Notable Things Seen by Cavaliere Wild Scull, and by Signore de la Hire on Their Famous Voyage From the Earth to the Moon.

Philippe de La Hire was a real French astronomer; nothing is known of Scull, and in the second printing Morghen replaced him with natural philosopher Bishop John Wilkins as a putative source of his fantastic images.

As to life on the moon, it’s pretty wild — among other things, the lunar inhabitants live in pumpkins to protect themselves from wild beasts. You can see the whole series at Public Domain Review.

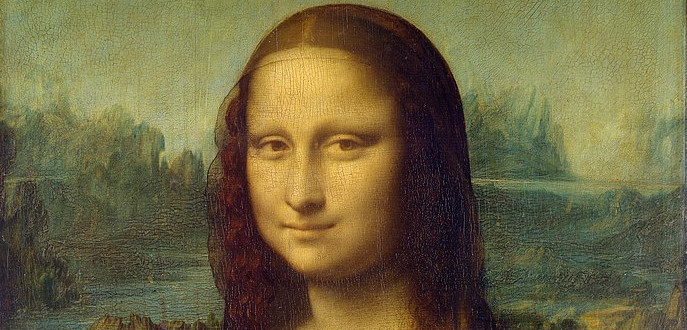

“In a lecture on ‘Beauty and Morality,’ at the University of London, one Kane S. Smith called the ‘Mona Lisa’ of Leonardo da Vinci ‘one of the most actively evil pictures ever painted, the embodiment of all evil the painter could imagine put into the most attractive form he could devise.'”

Literary Digest, Jan. 3, 1914:

“The lecturer admitted that it was an exquisite piece of painting, but said, ‘if you look at it long enough to get into its atmosphere, I think you will be glad to escape from its influence. It has an atmosphere of indefinable evil.'”

“The audience is stated to have applauded enthusiastically, but it is probable they would have applauded equally as heartily if the lecturer had found the influences of the picture good.”