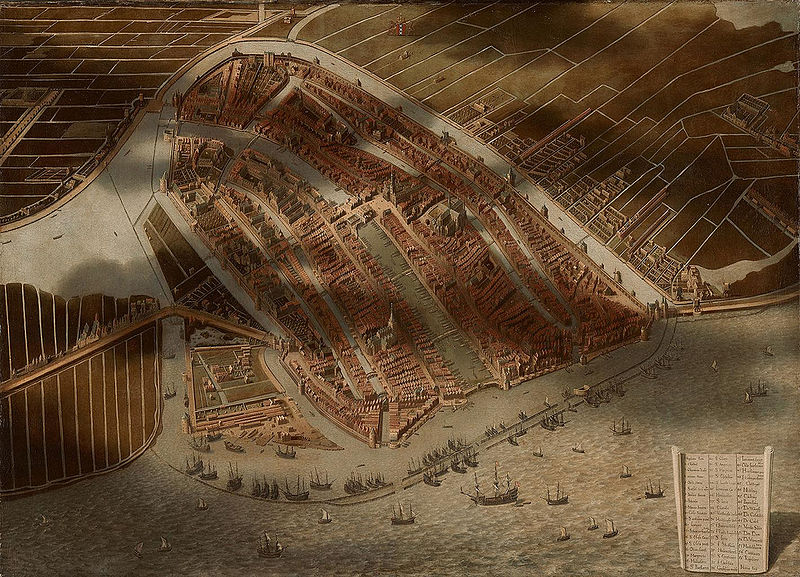

This bird’s-eye view of Amsterdam, painted in 1652 by Dutch artist Jan Micker, depicts even the shadows of clouds.

It presents the city as it appeared in 1538 … because it was inspired by an even earlier painting, by Cornelis Anthonisz (below).

This bird’s-eye view of Amsterdam, painted in 1652 by Dutch artist Jan Micker, depicts even the shadows of clouds.

It presents the city as it appeared in 1538 … because it was inspired by an even earlier painting, by Cornelis Anthonisz (below).

habitacle

n. a dwelling-place or habitation

crispation

n. the state of being curled

affabrous

adj. ingeniously made or finished

rhathymia

n. light-heartedness

British artist Alex Chinneck designed this unzipped building facade for Milan Design Week in 2019. The theme is continued inside, where giant zippers create openings in walls and the floor. More at Dezeen.

Founded in 1957, catalog showroom Best Products distinguished itself with highly unorthodox facades, designed by architect James Wines for nine retail facilities across the United States. This one, the “Indeterminate Facade” in Houston, Texas, was said to have appeared in more books on 20th-century architecture than photographs of any other modern structure. The company eventually went bankrupt, and most of the buildings have been redesigned or demolished, but one in Richmond, Va., with a forest in its entryway, is now home to a Presbyterian church.

See more at Archilaces.

In the Kinkerbuurt, Amsterdam, the streets are named after Dutch poets and writers of the 18th and 19th centuries. Correspondingly, Yugoslavian artist Sanja Medic transformed the façade of a local building into a case holding 250 ceramic “books” by these authors.

It’s a substantial library — each volume weighs more than 25 kg, so the frontage had to be reinforced to support them.

Dutch designer Wouter Scheublin created this walking table in 2006, inspired by a walking mechanism proposed by Russian mathematician Pafnuty Chebyshev in the 19th century:

Scheublin’s table walks using a system of cranks and rods, “perplexing our perception of the ordinarily static piece of furniture.”

His countryman Theo Jansen sets wind-driven mechanical creatures walking on Dutch beaches.

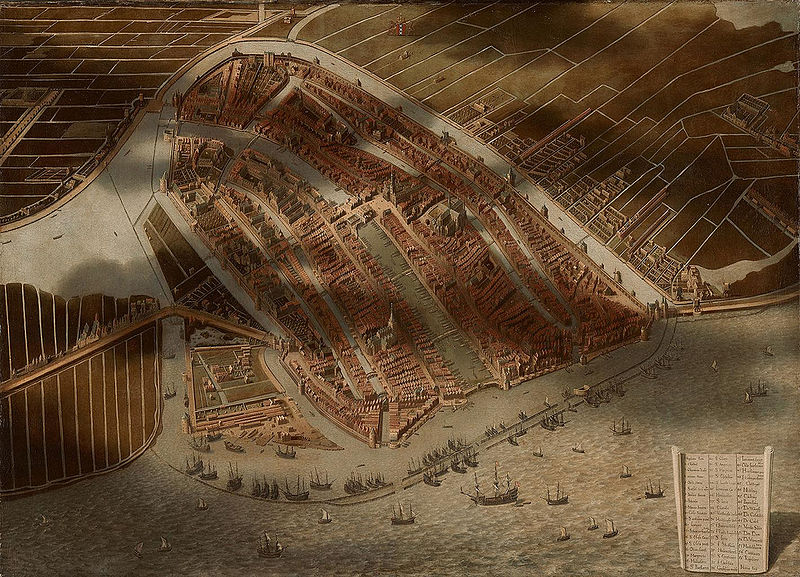

The Shrine of Remembrance in Melbourne, built to honor the men and women of Victoria who served in World War I, contains a marble stone engraved with the words Greater love hath no man (from John 15:13, “Greater love hath no man than this, that a man lay down his life for his friends”).

The shrine is constructed so that once a year, at 11 a.m. on Nov. 11, a ray of sunlight will shine through an aperture in the roof to illuminate the word love.

Arizona’s Anthem Veterans Memorial has a related design.

11/14/2020 UPDATE: An interesting addendum: The introduction of daylight saving in 1971 led designers to introduce a system of mirrors to ensure the right timing. Thanks to everyone who wrote in about this.

In 1995, Alma College mathematician John F. Putz counted the measures in Mozart’s piano sonatas, comparing the length of the exposition (a) to that of the development and recapitulation (b):

| Köchel and movement | a | b | a + b |

| 279, I | 38 | 62 | 100 |

| 279, II | 28 | 46 | 74 |

| 279, III | 56 | 102 | 158 |

| 280, I | 56 | 88 | 144 |

| 280, II | 56 | 88 | 144 |

| 280, II | 24 | 36 | 60 |

| 280, III | 77 | 113 | 190 |

| 281, I | 40 | 69 | 109 |

| 281, II | 46 | 60 | 106 |

| 282, I | 15 | 18 | 33 |

| 282, III | 39 | 63 | 102 |

| 283, I | 53 | 67 | 120 |

| 283, II | 14 | 23 | 37 |

| 283, III | 102 | 171 | 273 |

| 284, I | 51 | 76 | 127 |

| 309, I | 58 | 97 | 155 |

| 311, I | 39 | 73 | 112 |

| 310, I | 49 | 84 | 133 |

| 330, I | 58 | 92 | 150 |

| 330, III | 68 | 103 | 171 |

| 332, I | 93 | 136 | 229 |

| 332, III | 90 | 155 | 245 |

| 333, I | 63 | 102 | 165 |

| 333, II | 31 | 50 | 81 |

| 457, I | 74 | 93 | 167 |

| 533, I | 102 | 137 | 239 |

| 533, II | 46 | 76 | 122 |

| 545, I | 28 | 45 | 73 |

| 547, I | 78 | 118 | 196 |

| 570, I | 79 | 130 | 209 |

He found that the ratio of b to a + b tends to match the golden ratio. For example, the first movement of the first sonata is 100 measures long, and of this the development and recapitulation make up 62. “This is a perfect division according to the golden section in the following sense: A 100-measure movement could not be divided any closer (in natural numbers) to the golden section than 38 and 62.”

Ideally there are two ratios that we could hope would hew to the golden section: The first relates the number of measures in the development and recapitulation section to the total number of measures in each movement, and the second relates the length of the exposition to that of the recapitulation and development. The first of these gives a correlation coefficient of 0.99, the second of only 0.938.

So it’s not as impressive as it might be, but it’s still striking. “Perhaps the golden section does, indeed, represent the most pleasing proportion, and perhaps Mozart, through his consummate sense of form, gravitated to it as the perfect balance between extremes,” Putz writes. “It is a romantic thought.”

(John F. Putz, “The Golden Section and the Piano Sonatas of Mozart,” Mathematics Magazine 68:4 [October 1995], 275-282.)

This image turned up in the subreddit Confusing Perspectives back in February.

One user wrote, “Someone needs to make this into real sheet music and see how it sounds. I’m curious now.”

Another version:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MT5erpy3kOA