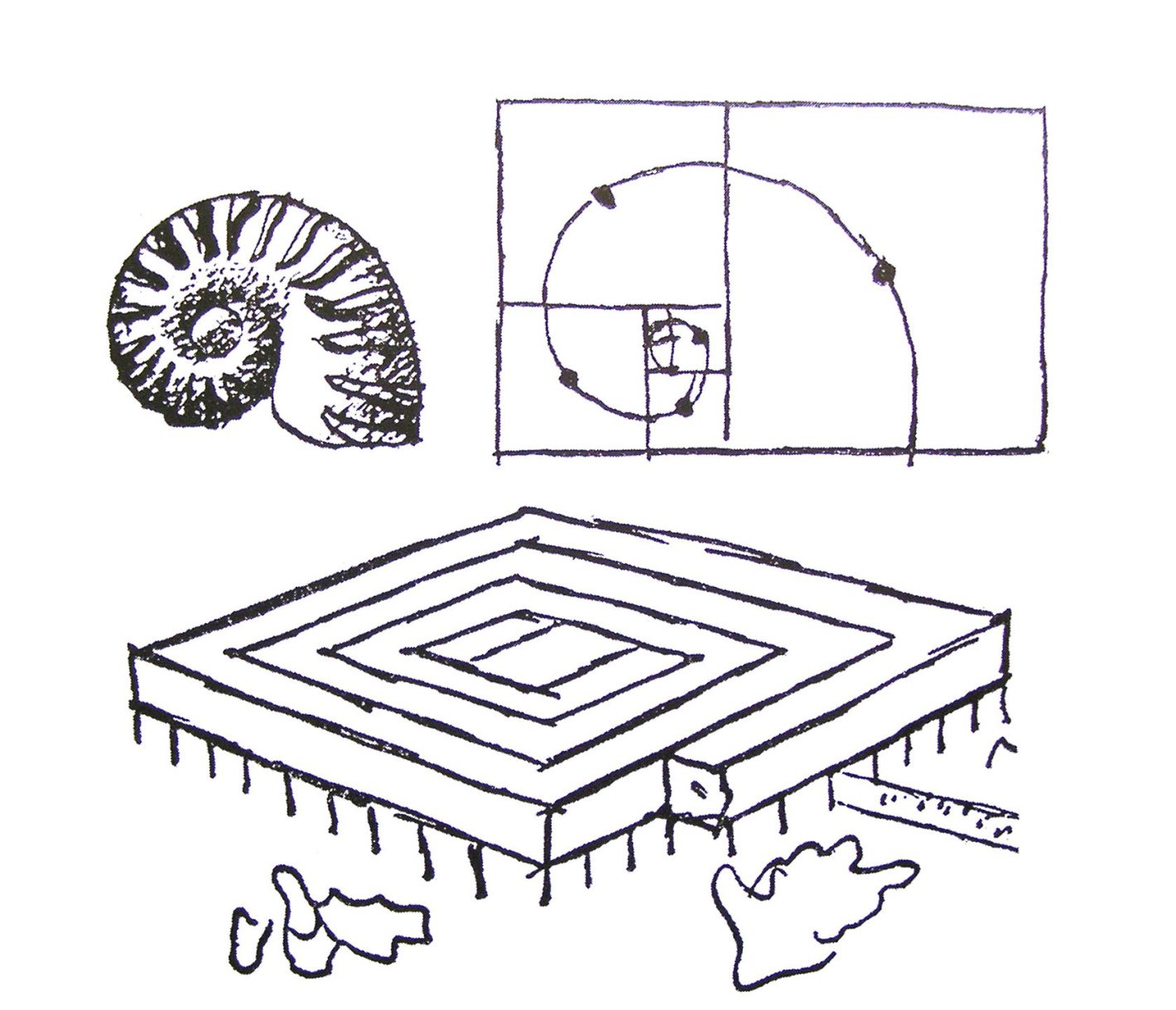

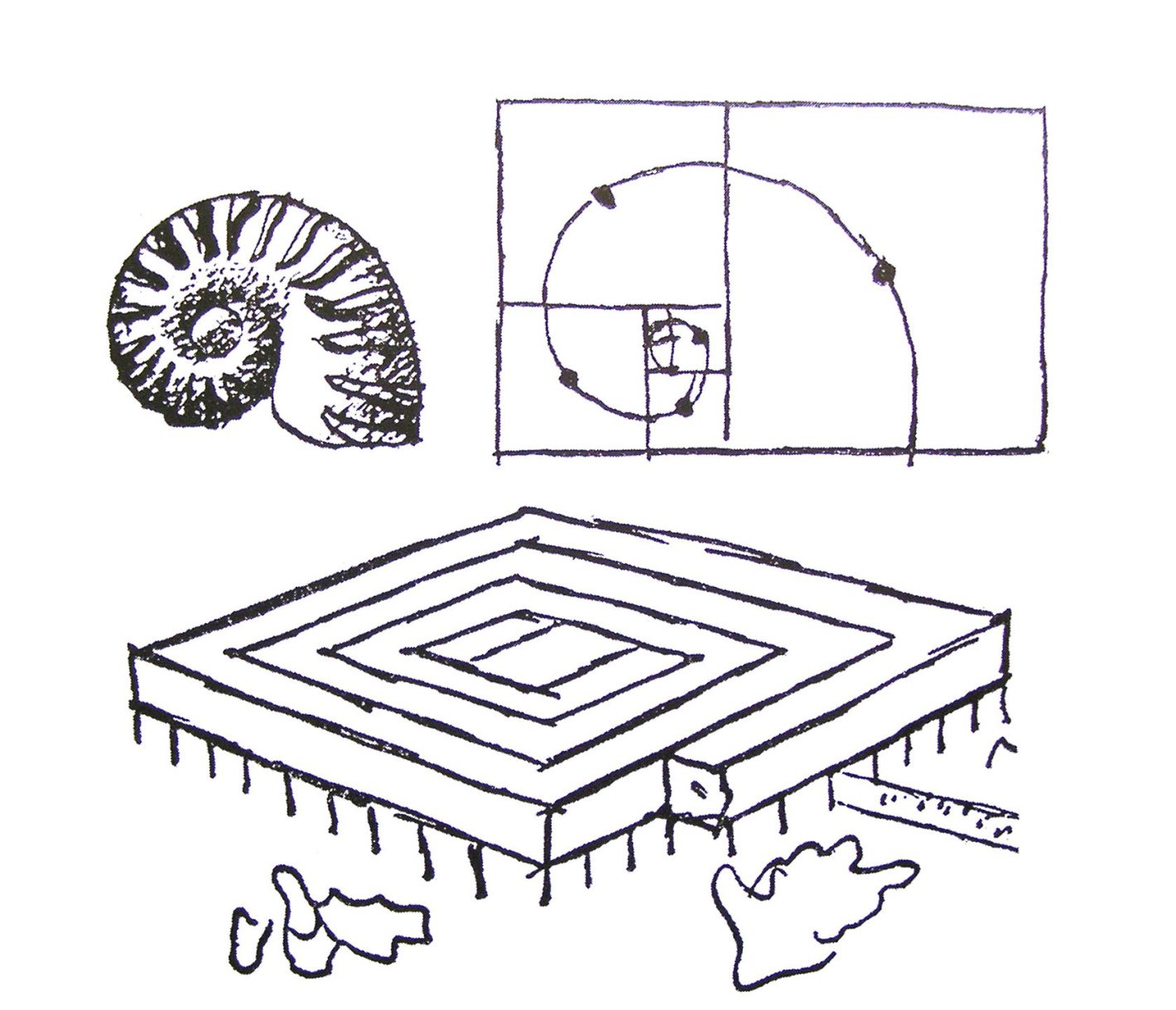

How can an art gallery accommodate a growing collection? In 1931 Le Corbusier proposed a Musée à croissance illimitée that would grow like a snail’s shell, coiling in a rectangular spiral as needs required and as funds became available.

“The means of orienting one’s self in the museum is provided by the rooms at half-height which form a ‘swastika,'” he explained. “Every time a visitor, in the course of his wanderings, finds himself under a lowered ceiling he will see, on one side, an exit to the garden, and on the opposite side, the way to the central hall. The Museum can be developed to a considerable length without the square spiral becoming a labyrinth.”

He presented the idea as a museum for Philippeville in North Africa in 1939, in a town planning project for Saint-Dié in 1945, and in a competition design to reconstruct the center of Berlin in 1958, but it was never realized.

(From Ulrich Conrads and Hans G. Sperlich, The Architecture of Fantasy, 1962.)