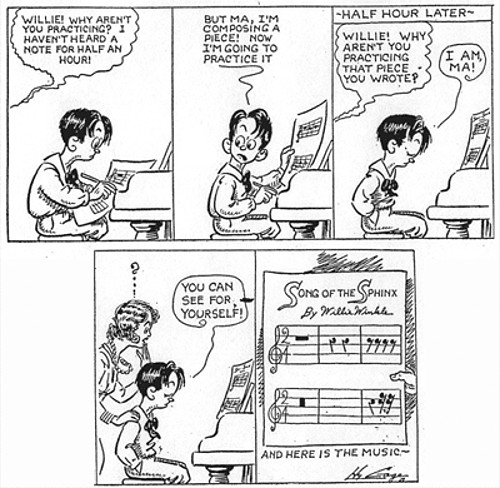

In John Cage’s 1952 composition 4’33”, the performer is instructed not to play his instrument.

American music critic Kyle Gann discovered this 1932 cartoon in The Etude, a magazine for pianists.

The cartoonist’s name, remarkably, is Hy Cage.

In John Cage’s 1952 composition 4’33”, the performer is instructed not to play his instrument.

American music critic Kyle Gann discovered this 1932 cartoon in The Etude, a magazine for pianists.

The cartoonist’s name, remarkably, is Hy Cage.

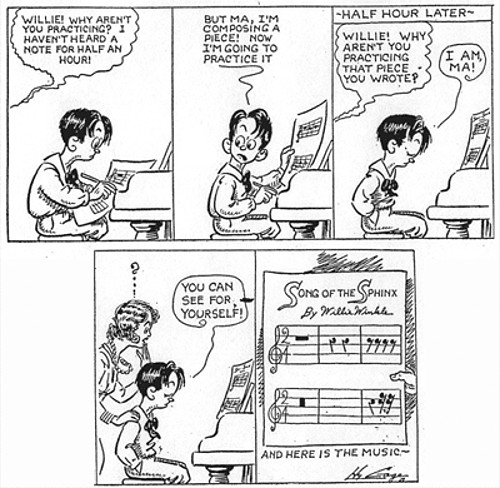

The transept of the Cathedral of Milan features a 1562 statue of the flayed Christian martyr Saint Bartholomew wearing his own skin as a robe.

It’s inscribed I was made not by Praxiteles but by Marco d’Agrate.

Michael Snow’s 1967 experimental film Wavelength consists essentially of an extraordinarily slow 45-minute zoom on a photograph on the wall of a room. William C. Wees of McGill University points out that this raises a philosophical question: What visual event does this zoom create? In a tracking shot, the camera moves physically forward, and its viewpoint changes as a person’s would as she advanced toward the photo. In Wavelength (or any zoom) the camera doesn’t move, and yet something is taking place, something with no analogue in ordinary experience.

“If I actually walk toward a photograph pinned on a wall, I find that the photograph does, indeed, get larger in my visual field, and that things around it slip out of view at the peripheries of my vision. The zoom produces equivalent effects, hence the tendency to describe it as ‘moving forward.’ But I am really imitating a tracking shot, not a zoom. … I think it is safe to say that no perceptual experience in the every-day world can prepare us for the kind of vision produced by the zoom.”

“What, in a word, happens during a viewing of that forty-five minute zoom? And what does it mean?”

(From Nick Hall, The Zoom: Drama at the Touch of a Lever, 2018.)

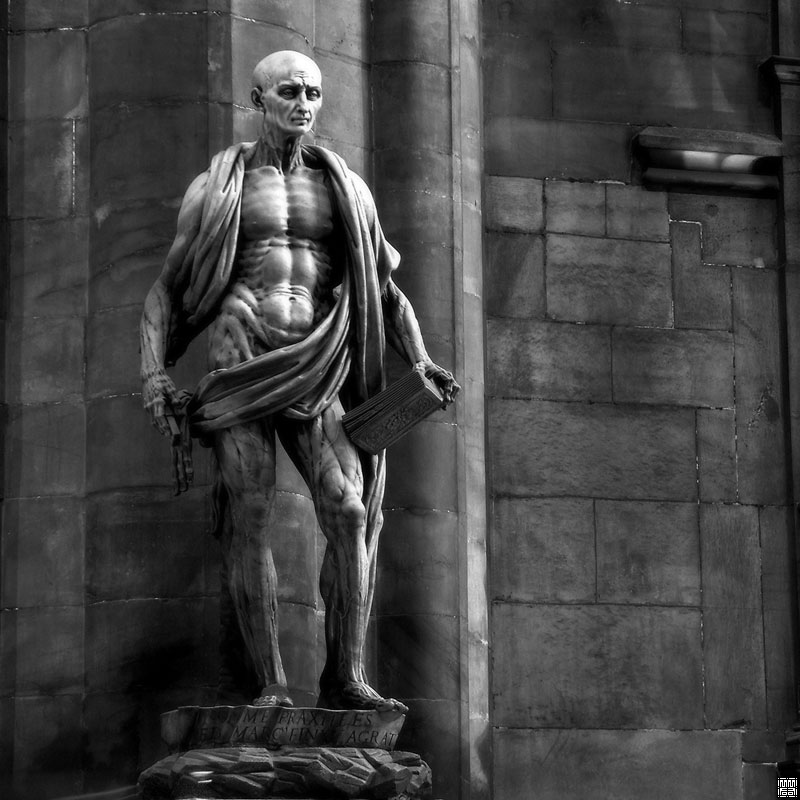

In 1930 French architect Emilio Terry offered a model of a spiral house that he called en colimaçon (“snail-style”), illustrating his view that architecture expressed a “dream to be realized.”

It looks odd, but the interior is relatively conventional. “Although the snail shape has been imposed on the exterior,” writes Ulrich Conrads in The Architecture of Fantasy, “no advantage is derived from it, either regarding the total volume or the interrelationship of the spatial sections.”

In 1920, after Lenin delivered a speech in Petrograd to troops departing to fight in the Soviet-Polish war, Russian artist El Lissitzky challenged his architecture students to design a speaker’s platform on a public square. The result was the Lenin Tribune, a rostrum that can bear its speaker aloft to address a crowd of any size. In a letter to the art historian and critic Adolf Behne, Lissitzky wrote:

I have now received some sketches of former works and have reconstructed the design. Therefore I do not sign it as my personal work, but as a workshop production. The diagonally-standing structure of iron latticework supports the movable and collapsible balconies: the upper one for the speaker, the lower one for guests. An elevator takes care of transportation. On top there is a panel intended for slogans during the day and as a projection screen at night. The gesture of the entire speaker’s platform is supposed to enhance the motions of the speaker. (The figure is Lenin.)

Here the message reads PROLETARIAT. Lissitzky later said he regretted not publishing the design when Vladimir Tatlin’s Monument to the Third International was attracting attention, so that the two might have competed against one another.

Moscow programmer Ani Abakumova makes portraits by spanning circular hoops with lengths of colored thread.

A computer dictates the placement of the threads, but she produces each portrait by hand.

More at her Instagram page.

Keep the Faith, an ambigram by typographer John Langdon. It reads the same upside down.

There’s much more at his site.

South Korean artist Dain Yoon uses her face as a canvas for endlessly inventive illusions.

More on her Instagram page.

In 1924 the eccentric Lord Berners composed a “Funeral March for a Rich Aunt”:

The musical direction is Allegro giocoso — “fast and cheerful.”