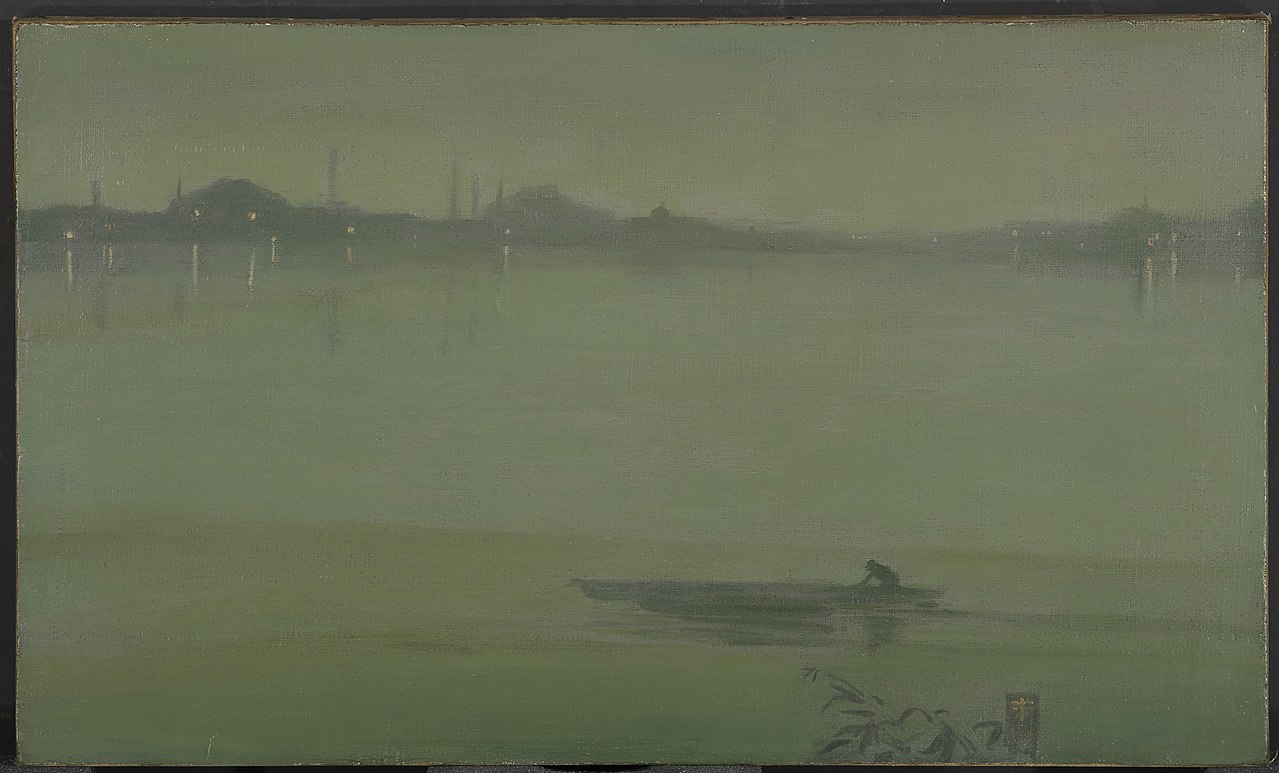

A woman told James McNeill Whistler that the view of the Thames she had just seen reminded her exactly of his series of paintings.

He told her, “Yes, madam. Nature is creeping up.”

A woman told James McNeill Whistler that the view of the Thames she had just seen reminded her exactly of his series of paintings.

He told her, “Yes, madam. Nature is creeping up.”

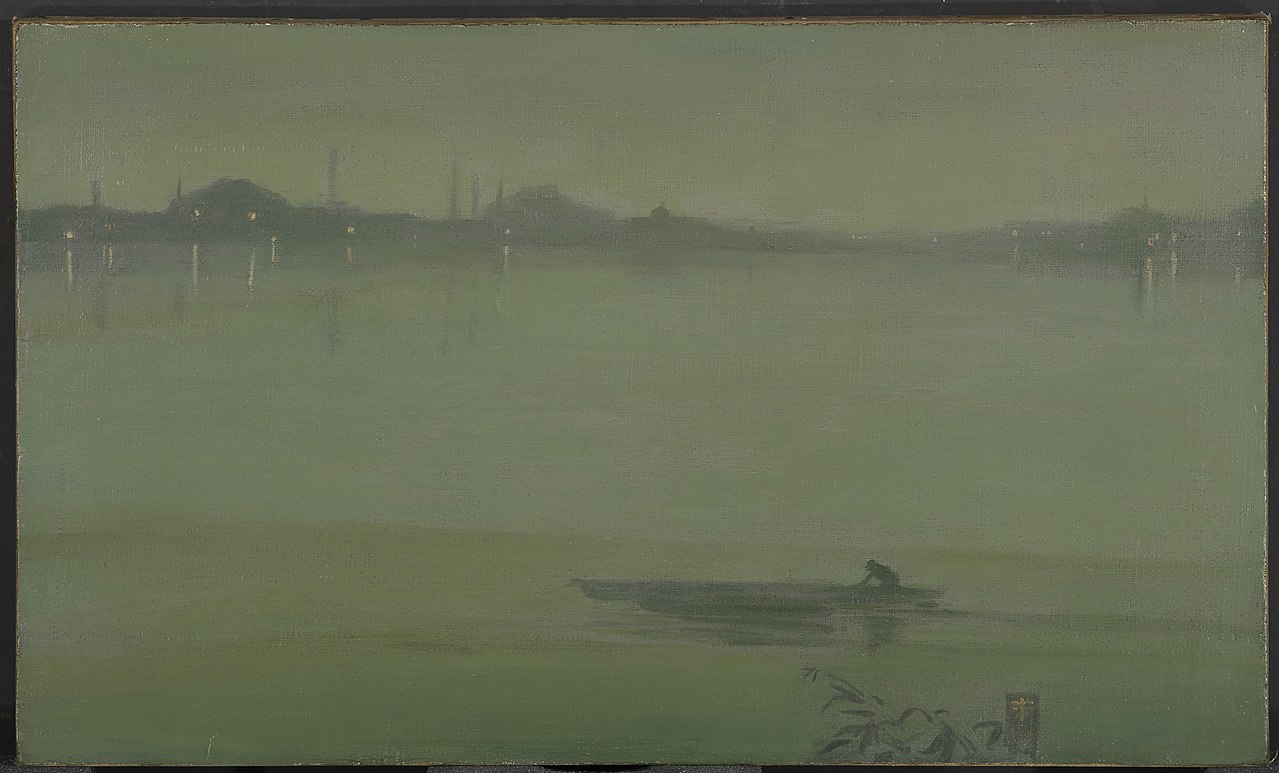

“Westminster Quarters,” the clock chime melody associated most closely with Big Ben, consists of four notes played in a characteristic permutation at each quarter of the hour:

In 1933 composer Ernst Toch fled Germany for London, where one foggy night he was crossing Westminster Bridge and heard the familiar chimes strike the full hour. He wrote:

The theme lingered in my mind for a long while and evolved into other forms, always somehow connected with the original one. It led my imagination through the vicissitudes of life, through joy, humour and sorrow, through conviviality and solitude, through the serenity of forest and grove, the din of rustic dance, and the calm of worship at a shrine; through all these images the intricate summons of the quarterly fragments meandered in some way, some disguise, some integration; until after a last radiant rise of the full hour, the dear theme, like the real chimes themselves that accompanied my lonely walk, vanished into the fog from which it had emerged.

On the boat to New York he wrote Big Ben: Variation-Fantasy on the Westminster Chimes:

(From Chris McKay, Big Ben, 2010.)

06/04/2018 The chimes also inspired Louis Vierne’s 1927 organ piece Carillon de Westminster. (Thanks, Jon.)

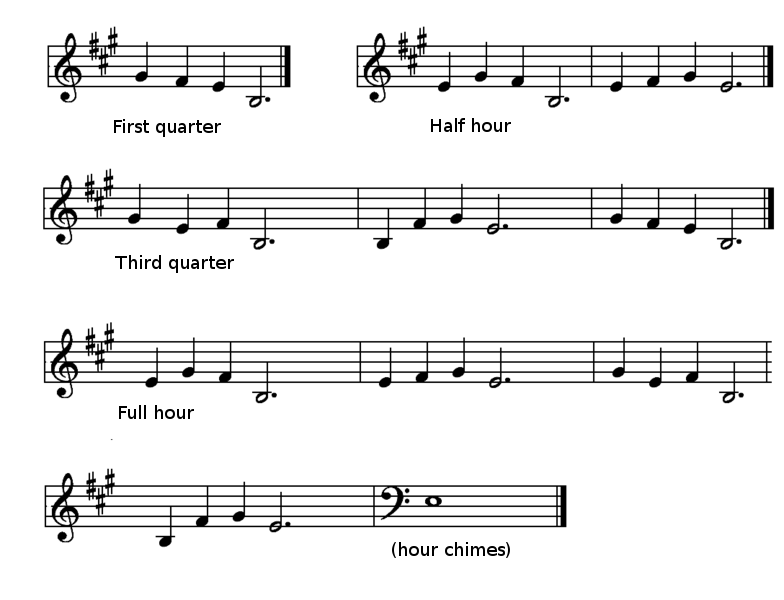

Maybe this is symbolic — the U.S. Capitol contains a pair of “doors to nowhere” that serve no purpose.

In 1901 sculptor Louis Amateis designed a set of bronze doors to grace the reconstructed façade of the building’s West Front. But when the doors were cast in 1910, legislation for the improvement still had not been authorized, so they couldn’t be installed.

The “Amateis Doors” were displayed in various museums until 1967 and then placed in storage. They were finally hung in the Capitol in 1972, just downstairs from the Rotunda … where they seem to promise great things but ultimately lead nowhere.

In 1948 the Italian composer Giacinto Scelsi entered a sanatorium in the Swiss Alps, where he began to pass the time by repeatedly striking a single piano key and listening intently to its sound. He said later:

Reiterating a note for a long time, it grows large, so large that you even hear harmony growing inside it. … When you enter into a sound, the sound envelops you and you become part of the sound. Gradually, you are consumed by it and you need no other sound. … All possible sounds are contained in it.

The result, eventually, was his 1959 composition Quattro pezzi (ciascuno su una nota sola) (“Four Pieces, Each on a Single Note”) for chamber orchestra, in which each movement concentrates on a single pitch, with varying timbre and dynamics.

He wrote, “I will say only that in general, western classical music has devoted practically all of its attention to the musical framework, which it calls the musical form. It has neglected to study the laws of sonorous energy, to think of music in terms of energy, which is life. … The inner space is empty.”

While we’re at it: Here’s how Rick Astley’s “Never Gonna Give You Up” would sound if all the notes were C:

(Gregory N. Reish, “Una Nota Sola: Giacinto Scelsi and the Genesis of Music on a Single Note,” Journal of Musicological Research 25 [2006] 149–189.)

In 1990, two thieves dressed as policemen walked into Boston’s Gardner museum and walked out with 13 artworks worth half a billion dollars. After 28 years the lost masterpieces have never been recovered. In this week’s episode of the Futility Closet podcast we’ll describe the largest art theft in history and the ongoing search for its solution.

We’ll also discover the benefits of mustard gas and puzzle over a surprisingly effective fighter pilot.

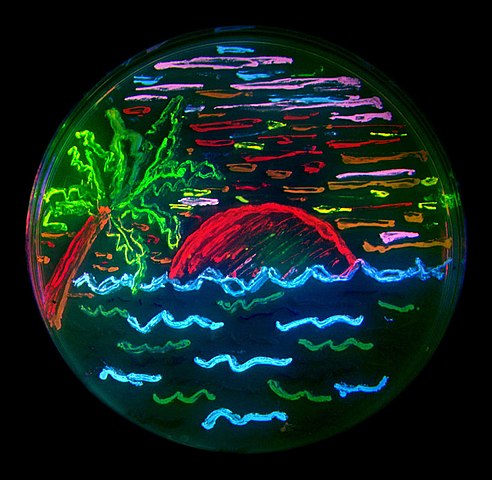

Biochemist Roger Tsien won the 2008 Nobel prize in chemistry for his contributions to knowledge of green fluorescent protein, a complex of amino acid residues that glow vividly when exposed to ultraviolet light.

Inspired, Nathan Shaner, a researcher in Tsien’s lab, painted this San Diego beach scene using an eight-color palette of bacterial colonies expressing fluorescent proteins.

Alexander Fleming was drawing “germ paintings” in the 1930s.

stridulous

adj. emitting a particularly harsh or shrill sound

tumultuary

adj. restless; agitated; unquiet

emportment

n. a fit of passion; anger, fury

bangstry

n. masterful violence

Of the numerous war scenes in operas of all ages, it is worth noting one in particular for its extraordinary tempo marking. The opera Sofonisba (1762) by Tommaso Traetta (or Trajetta) opens with a battle scene in which two oboes, two horns (pitched in C and D respectively), and a string band are instructed to play ‘Allegrissimo e strepitosissimo,’ literally, ‘very joyfully and with much animation and gaiety and extremely noisily and boisterously.’

— Robert Dearling, The Guinness Book of Music Facts & Feats, 1976

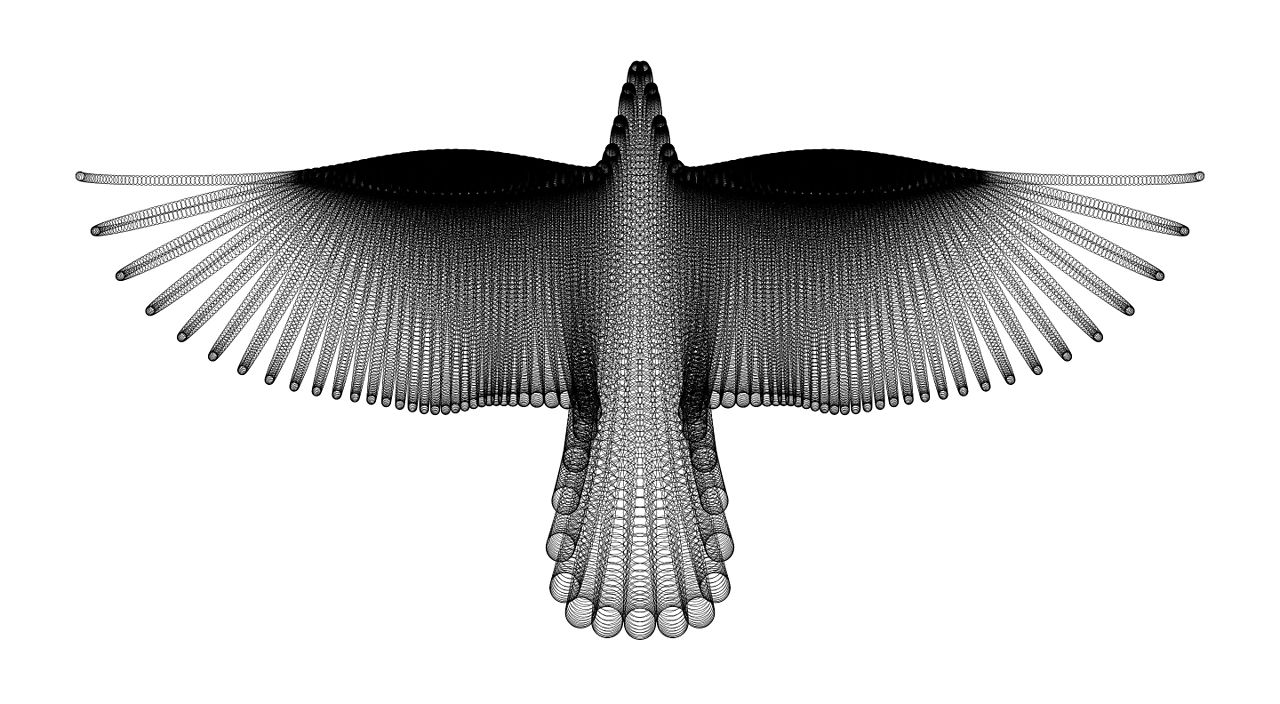

Iranian artist Hamid Naderi Yeganeh makes art from math. The image above shows all circles of the form , for k = -10000, -9999, … , 9999, 10000, where

In 1927, Ukrainian conductor Nikolai Malko played Vincent Youmans’ song “Tea for Two” for Dmitri Shostakovich and bet 100 roubles that the composer couldn’t reorchestrate it from memory in less than an hour.

Shostakovich did it in 45 minutes.

He later incorporated the arrangement into Tahiti Trot and used it as an entr’acte in his 1930 ballet The Golden Age.

(Thanks, Allen.)