Susan Cahill performs a self-referential piece by Tom Johnson at the 2014 Festival Mozaic.

(Via MetaFilter.)

Susan Cahill performs a self-referential piece by Tom Johnson at the 2014 Festival Mozaic.

(Via MetaFilter.)

Japanese artist Tatsuo Horiuchi creates digital art in Microsoft Excel. As he neared retirement he decided to take up painting, but he wanted to save the cost of brushes and pencils, so he used a tool he already owned, Microsoft’s popular spreadsheet program.

“I never used Excel at work but I saw other people making pretty graphs and thought, ‘I could probably draw with that,'” he told My Modern Met. “Graphics software is expensive, but Excel comes pre-installed in most computers … And it has more functions and is easier to use than Paint.”

He began painting in Excel in the year 2000. “I set a goal,” he says, “in 10 years, I wanted to paint something decent that I could show to people.” After only six years he took first prize at the Excel Autoshape Art Contest, and he’s been at it now for more than 15 years.

He sells the digital paintings as limited-edition prints that you can see and purchase here.

University of Minnesota percussionist Gene Koshinski’s composition “As One” has two performers (here, Koshinski and Tim Broscious) complementing each other on identical setups, splitting one complex piece into two complex halves.

More about Koshinski at his website.

In his letters, Tchaikovsky comes to two contrary impressions of Venice in the space of three years:

April 17, 1874: “Now I will tell you about Venice. It is a place in which — had I to remain for long — I should hang myself on the fifth day from sheer despair. The entire life of the place centres in the Piazza San Marco. To venture further in any direction is to find yourself in a labyrinth of stinking corridors which end in some cul-de-sac, so that you have no idea where you are, or where to go, unless you are in a gondola. A trip through the Canale Grande is well worth making, for one passes marble palaces, each one more beautiful and more dilapidated than the last. In fact, you might suppose yourself to be gazing upon the ruined scenery in the first act of Lucrezia. But the Doge’s Palace is beauty and elegance itself; and then the romantic atmosphere of the Council of Ten, the Inquisition, the torture chambers, and other fascinating things. I have thoroughly ‘done’ this palace within and without, and dutifully visited two others, and also three churches, in which were many pictures by Titian and Tintoretto, statues by Canova, and other treasures. Venice, however — I repeat it — is very gloomy, and like a dead city. There are no horses here, and I have not even come across a dog.”

November 16, 1877: “Venice is a fascinating city. Every day I discover some fresh beauty. Yesterday we went to the Church of the Frati, in which, among other art treasures, is the tomb of Canova. It is a marvel of beauty! But what delights me most is the absolute quiet and absence of all street noises. To sit at the open window in the moonlight and gaze upon S. Maria della Salute, or over to the Lagoons on the left, is simply glorious! It is very pleasant also to sit in the Piazza di San Marco (near the Café) in the afternoon and watch the stream of people go by. The little corridor-like streets please me, too, especially in the evening when the windows are lit up. In short, Venice has bewitched me … To-morrow I will look for a furnished apartment.”

(Thanks, Charlie.)

Giuseppe Sanmartino’s 1753 sculpture Veiled Christ is so convincing that for 200 years a legend circulated that an alchemist had transformed a real shroud into marble.

In fact a close examination shows that Sanmartino carved the whole work, shroud and all, from a single block of stone. Antonio Canova said he would give up 10 years of his own life to produce such a masterpiece.

When Croatian artists Olinka Vištica and Dražen Grubišic ended their four-year relationship in 2003, they joked about creating a museum to house all their leftover personal items. “We were thinking of how to preserve the beautiful moments we had together and not destroy everything,” Vištica said. Three years later, Grubišic suggested that they do this in earnest, and they created the Museum of Broken Relationships, displaying items left over from breakups around the world.

After ending an 18-month relationship with an abusive lover, a Toronto woman sent in a necklace and earrings he had given her. “The necklace was given as an apology after one night of abuse. He used it as leverage that I should do as he said. I finally broke it off. I keep the necklace as a reminder of what to look out for.”

A Berlin women donated the ax she’d used to chop up her partner’s furniture after she left her for another woman. “Every day I axed one piece of her furniture. I kept the remains there, as an expression of my inner condition. The more her room filled with chopped furniture acquiring the look of my soul, the better I felt. Two weeks after she left, she came back for the furniture. It was neatly arranged into small heaps and fragments of wood. She took that trash and left my apartment for good. The axe was promoted to a therapy instrument.”

Between 2006 and 2010, the collection toured the world and was seen by 200,000 people. It’s now found a permanent home in Zagreb, and in 2016 it opened another location in Los Angeles, next to the theater that hosts the Oscars. “I think in periods of suffering people become creative, and I think this is a catharsis,” Vištica told The Star. “I think that relationships, especially love relationships, influence us so much and they make us the people we are.”

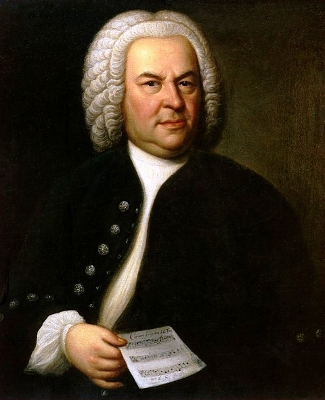

All of Johann Sebastian Bach’s surviving brothers were named Johann: Johann Rudolf, Johann Christoph, Johann Balthasar, Johannes Jonas, and Johann Jacob. His father was Johann Ambrosius Bach, and his sister was Johanna Juditha.

By contrast, his other sister, Marie Salome, “stuck out like a sore thumb,” writes Jeremy Siepmann in Bach: Life and Works. “And they all had grandparents and uncles and cousins whose names were also Johann, something. Johann Sebastian’s own children included Johann Gottfried, Johann Christoph, Johann August, Johann Christian, and Johanna Carolina.”

(Thanks, Charlie.)

Like his Celui qui tombe of 2014, acrobat Yoann Bourgeois’s La mécanique de l’Histoire is entirely abstract and yet freighted with meaning.

He presented it at the Panthéon in Paris last year — the site of Léon Foucault’s original rotation-demonstrating pendulum.

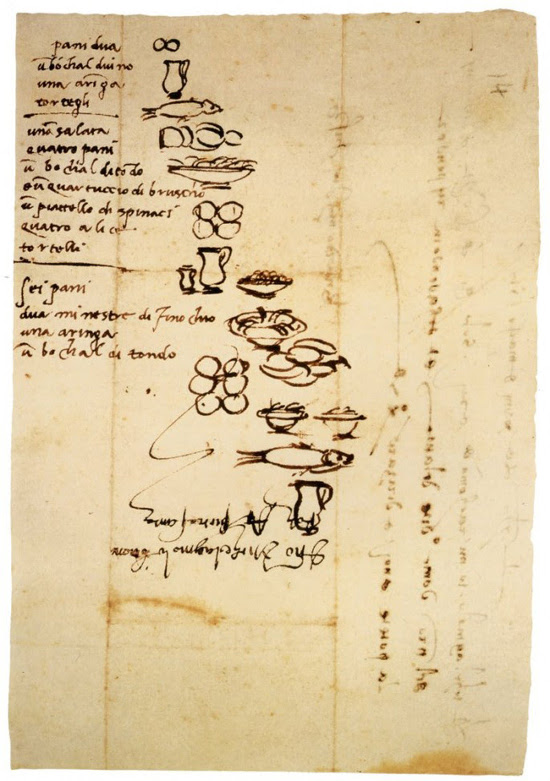

When the Seattle Art Museum presented an exhibition of Michelangelo’s early drawings in 2009, it included three menus that the sculptor had scrawled on the back of an envelope in 1518 — grocery lists for a servant.

Oregonian reviewer Steve Duin explained, “Because the servant he was sending to market was illiterate, Michelangelo illustrated the shopping lists — a herring, tortelli, two fennel soups, four anchovies and ‘a small quarter of a rough wine’ — with rushed (and all the more exquisite for it) caricatures in pen and ink.”

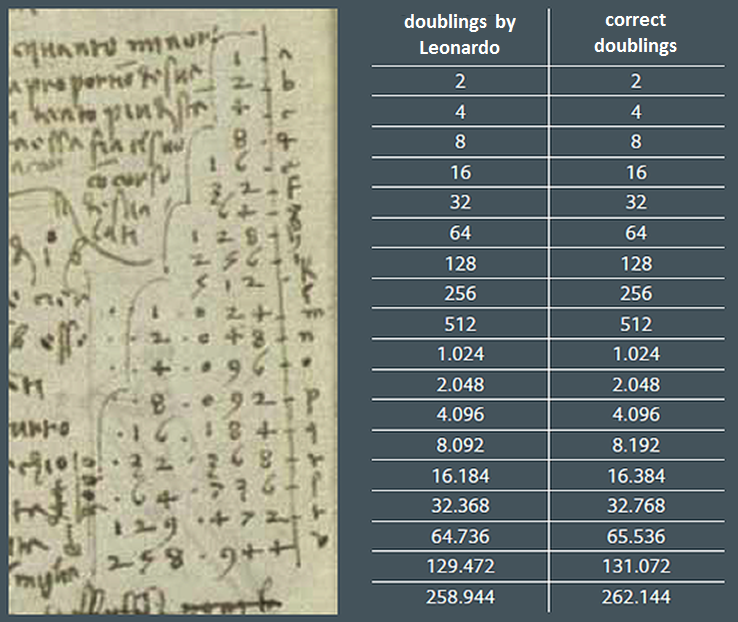

Related: In the 1490 manuscript below, Leonardo da Vinci tries to list successive doublings of 2 but mistakenly calculates 213 as 8092:

“Unmistakable this is a miscalculation of Leonardo and not of some sloppy copyists, as it was found in the original (mirrored) manuscript of da Vinci himself,” notes Ghent University computer scientist Peter Dawyndt. “That it was only discovered right now, five hundred years after da Vinci’s death, is probably due to the late discovery of the manuscript, barely fifty years ago.”

(Thanks, Peter.)

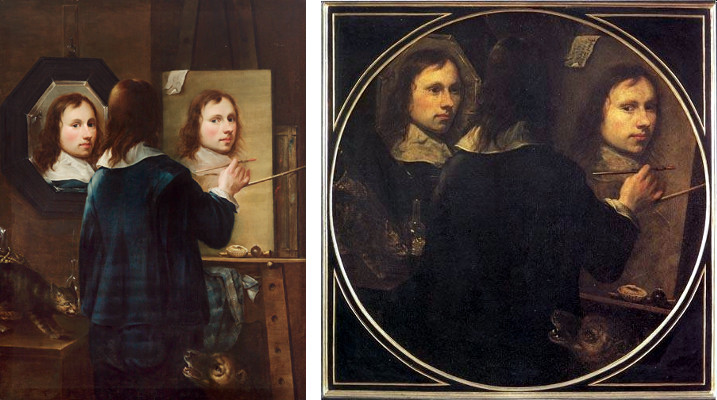

The Austrian painter Johannes Gumpp is remembered for only two works.

Both are self-portraits in which his back is turned to the viewer.