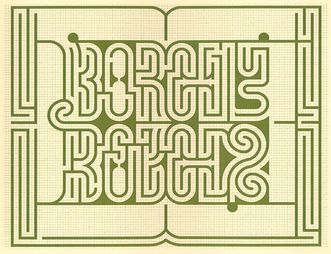

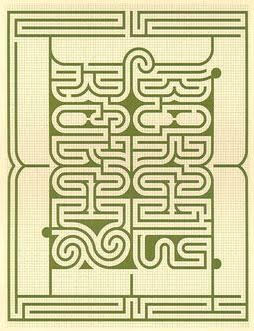

Japanese artist Motoi Yamamoto makes labyrinths out of salt. Working alone, he refines his initial sketches on computer and then builds them meticulously by hand, forming large, intricate mazes that fill entire rooms.

The final effect resembles the surface of the brain. Yamamoto lost his sister in 1994 to brain cancer, and he chose salt, a funeral material in Japan, “to heal my grief.” His first labyrinth had a single path from the exterior to the center; later works have offered multiple paths and often multiple entrances and exits.

After a work has been exhibited, he invites the public to help him destroy it and toss it back into the sea. “Drawing a labyrinth with salt is like following a trace of my memory,” he says. “Memories seem to change and vanish as time goes by; however, what I seek is to capture a frozen moment that cannot be attained through pictures or writings. What I look for at the end of the act of drawing could be a feeling of touching a precious memory.”