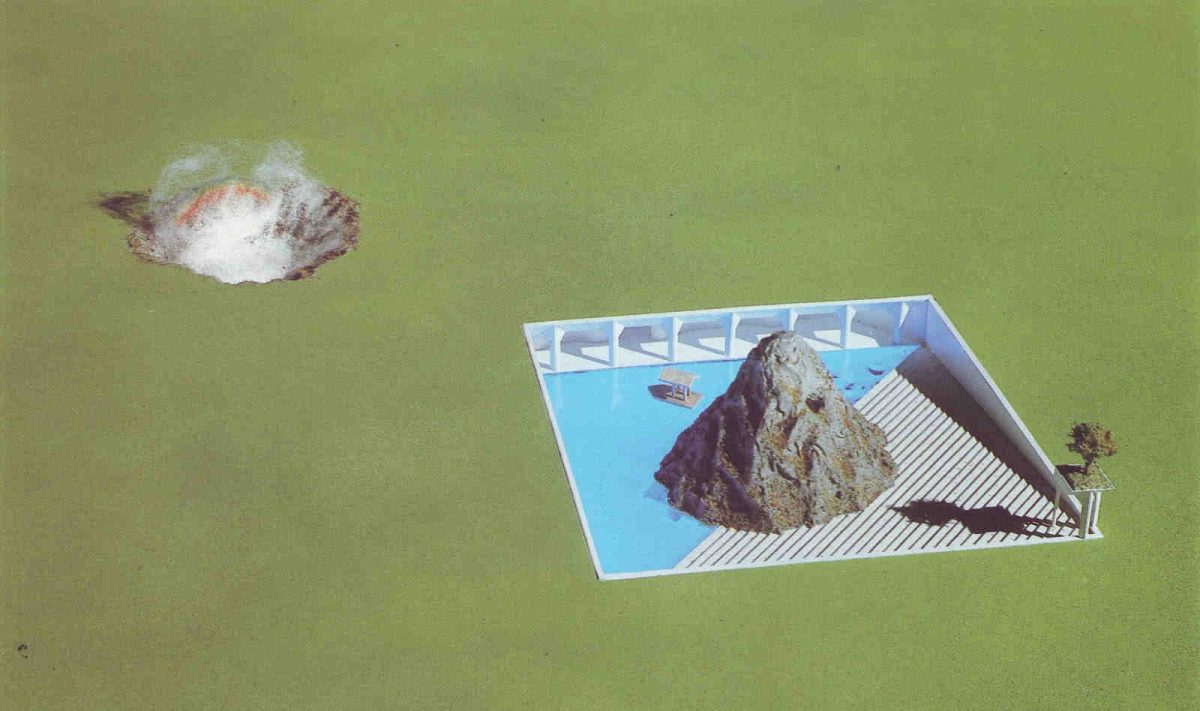

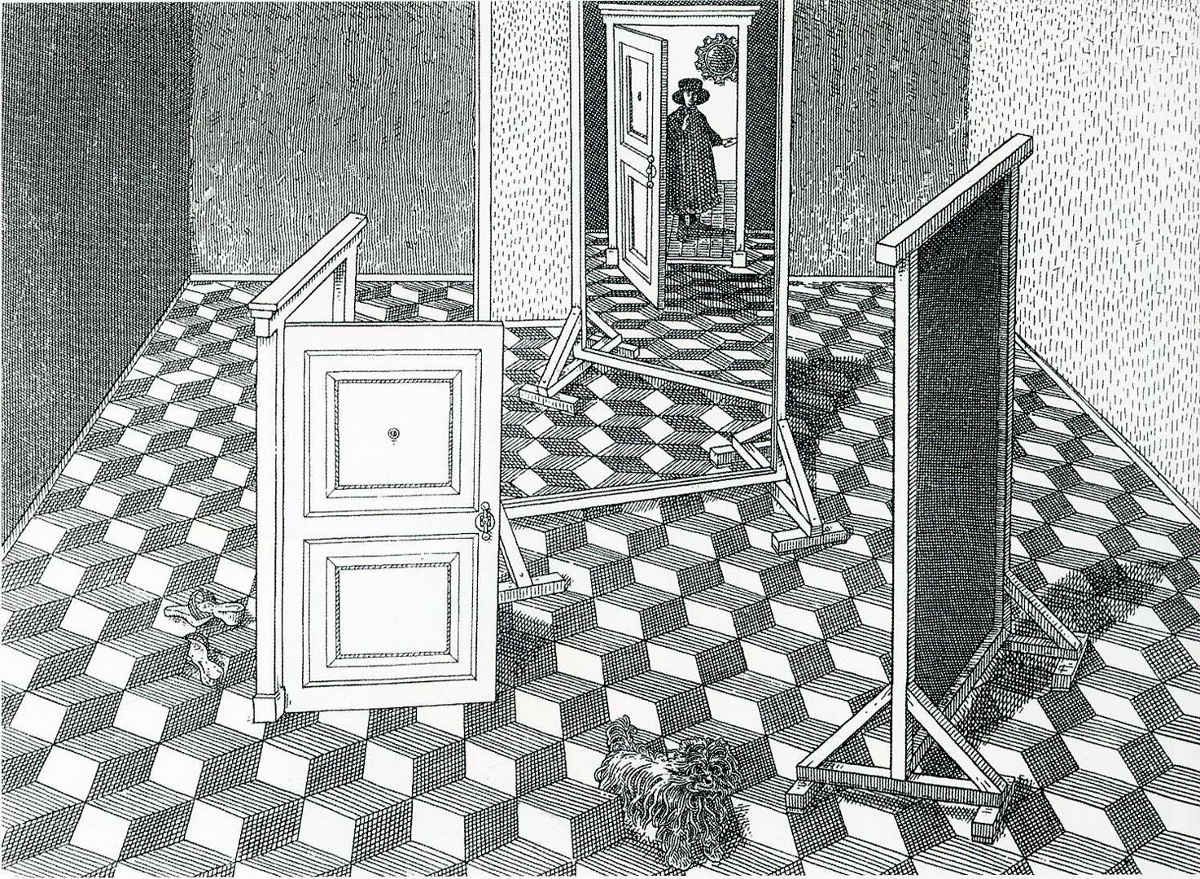

Here’s something odd: a painting of a young lady riding Aristotle like a pony.

In fact what’s surprising is how thoroughly we’ve forgotten this image, which was once one of the most common artistic motifs of the Northern Renaissance, figuring in scores of paintings, sculptures, and engravings.

The woman is Phyllis, the consort of Alexander the Great, who was a pupil of Aristotle. According to a 13th-century manuscript:

Once upon a time, Aristotle taught Alexander that he should restrain himself from frequently approaching his wife, who was very beautiful, lest he should impede his spirit from seeking the general good. Alexander acquiesced to him. The queen, when she perceived this and was upset, began to draw Aristotle to love her. Many times she crossed paths with him alone, with bare feet and disheveled hair, so that she might entice him.

At last, being enticed, he began to solicit her carnally.

‘This I will certainly not do, unless I see a sign of love, lest you be testing me. Therefore, come to my chamber crawling on hand and foot, in order to carry me like a horse. Then I’ll know that you aren’t deluding me.’

When he had consented to that condition, she secretly told the matter to Alexander, who lying in wait apprehended him carrying the queen. When Alexander wished to kill Aristotle, in order to excuse himself, Aristotle says,

‘If thus it happened to me, an old man most wise, that I was deceived by a woman, you can see that I taught you well, that it could happen to you, a young man.’

Hearing that, the king spared him, and made progress in Aristotle’s teachings.

This is an exemplum, a sort of parable designed to warn the reader away from a bad practice — in this case, allowing passion to overcome reason. But it’s nice to see the lesson taught to Aristotle, who once declared that the capacity for practical reason was undeveloped in children, absent in slaves, and “without authority” in women.

(Thanks, Dan.)