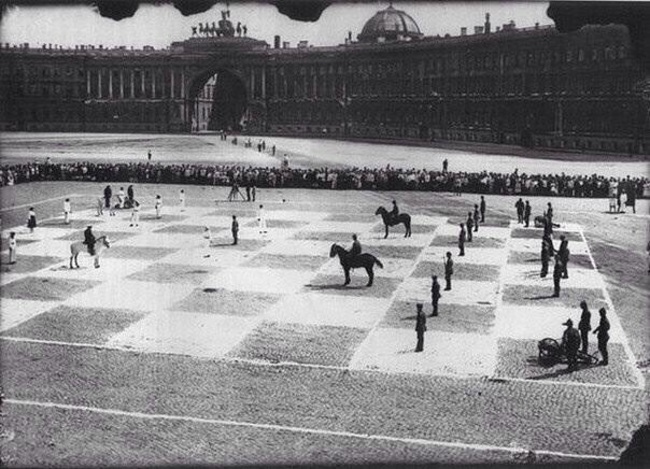

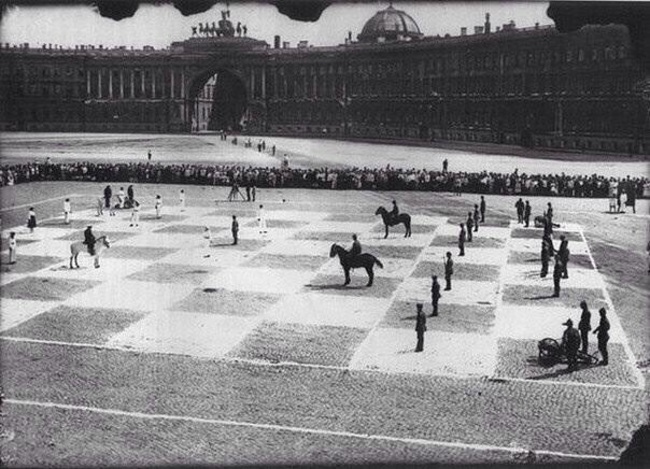

Human-scale chess has been played for centuries — the Italian town of Marostica has staged a game every two years since 1923, and the photo above shows actual soldiers (and cannon!) in a game in St. Petersburg in 1924.

In 2003 Sharilyn Neidhardt organized a game on a board represented by 64 city blocks on the Lower East Side of New York. Two expert players played the game on an ordinary board at the ABC No Rio gallery, in the middle of the street grid. Each time one of them made a move, the corresponding piece received a call or a text message (“go to f7”) and had to travel to the corresponding square, on foot or by bike or roller skate. If you were captured you became an ordinary person again.

Players were recruited online; each had to have a working cell phone, “be excruciatingly on time,” and be willing to spend about three hours awaiting orders. Neidhardt warned newcomers: center pawns can expect to be captured early, bishops and knights will cover a lot of territory, and kings will have a low-key opening and a busy endgame.

As of 2014, eight games had been played, in New York, San Francisco, Vancouver, and Austin. Here’s a knight’s diary of the New York game.

(From Karen O’Rourke, Walking and Mapping, 2013.)