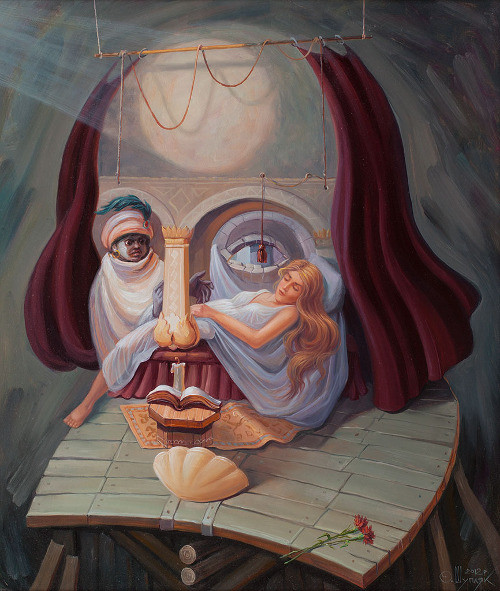

In the early 20th century, inspired by the scientific hope that the mind could evolve to ever-higher levels of consciousness, Russian poets tried to paint this higher reality with paradoxical statements that defied common sense. This movement reached its apotheosis in 1913 when Aleksei Kruchenykh wrote “Dyr bul shchyl,” an untranslatable arrangement of letters on a page. Kruchenykh added the legend “3 poems written in my own language different from others: its words do not have a definite meaning.” Kruchenykh named this new language zaum, Russian for transrational, because it transcends common sense and logic.

“For whom was Kruchenykh writing these poems?” asks Lynn Gamwell in Mathematics + Art. “He wrote for other avant-garde poets — he was a poet’s poet — and, according to his late-nineteenth-century biological worldview, the poets in his audience possessed expanded (more highly evolved) minds. Kruchenykh did not communicate in the ordinary sense — he deliberately chose obfuscation, made-up words. He composed his poems to reach a small, elite art audience whose brains, to his way of thinking, had evolved enough to perceive an actual infinity — the Absolute. In other words, the subject matter of his verse was neither nonsense nor an occult realm but rather an alleged higher ‘transrational’ level of reasoning.”