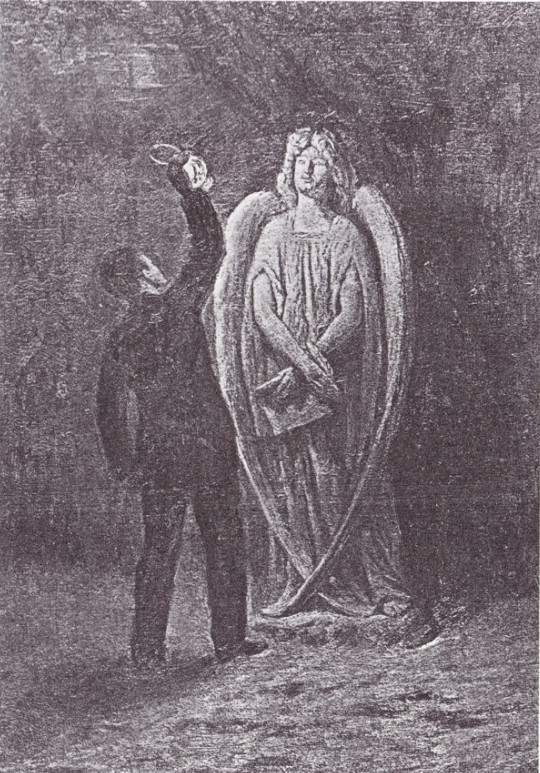

The residents of Brattleboro, Vt., awoke to a surprise on New Year’s Day 1856: An angel of snow stood at the corner of Linden and North Main streets, holding a pen and notebook as if ready to record the events of the new year.

The artist turned out to be 21-year-old Larkin Goldsmith Mead Jr., the son of a local lawyer. He had worked through the night to fashion the eight-foot figure by lantern light, shaping it by hand from snow brought to him by two friends. He sculpted some parts separately in order to mold them more easily, attaching them later with wet snow, and he poured water over the finished creation to give it a smooth finish. The Vermont Phoenix marveled:

The inhabitants of the village discovered ‘The Snow Angel,’ in the prismatic glow of the morning sun’s reflection. The early risers and pedestrians about town were amazed, when they drew near, to see what appeared at a distance like a school-boy’s work turned to a statue of such exquisite contour and grace of form. … The passing school-boy was awed for once, as he viewed the result of adept handling of the elements with which he was so roughly familiar, and the thought of snowballing so beautiful an object could never have dwelt in his mind. It is related that the village simpleton was frightened and ran away, and one eccentric citizen, who rarely deigned to bow to his fellow men, or women either, lifted his hat in respect after he had gazed a moment upon Mead’s work.

The angel was featured in newspapers in Boston and New York, and it brought Mead commissions for more lasting works, including a statue of Ethan Allen and a wooden figure symbolizing agriculture for the Montpelier statehouse. His later projects include Lincoln’s tomb in Springfield, Illinois.

In 1886 he reproduced the angel in marble — it stands in the public library in Brattleboro. Across the street, commemorating the site of the original angel, stands a drinking fountain designed by his brother, architect William Mead — who immortalized the family name in his own way.