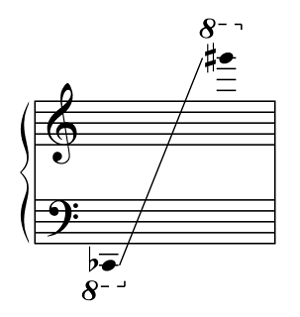

In The Book of the Harp (2005), John Marson mentions a musical oddity — in 1932, a committee devoted to equal temperament was so incensed at the Royal Schools of Music that it hauled them before London’s Central Criminal Court for obtaining money under false pretenses. From The Music Lover magazine, April 30, 1932:

There is a touch of knight errantry about the action of Lennox Atkins F.R.C.O., hon. sec. of the Equal Temperament Committee, in applying at Bow Street for process against the Associated Board of Examiners in Music on the grounds that they were not qualified to know whether the music was being played in tune or not, and that therefore their diplomas were valueless. It certainly savours of the ‘ingenious gentleman’ of La Mancha who tilted at windmills. The temperament question seems to have upon those who take it up an effect similar to that which temperament produces in a prima donna. They become, to say the least, unreasonable. Happily Mr Fry, the magistrate, decided that this was not a matter for a criminal court, so that Sir John B. McEwan and Sir Hugh Allen are not to be shot at dawn, as was at first feared.

McEwan headed the Royal Academy of Music and Allen the Royal College of Music at the time. I find a bit more in the Musical Times, June 1, 1932:

Candidates were allowed to pass off the tuner’s scale as their own, and to obtain certificates to which, the E.T.C. claimed, they were not in equity entitled. Every sound produced was the tuner’s and not the candidate’s. Famous examiners, such as the late Sir Frederick Bridge, had wrongly passed thousands of candidates in keyed instrument examinations. From the point of view of the E.T.C., the candidates were not really examined at all.

The magistrate added that if it was thought that the examiners’ knowledge was insufficient then civil proceedings might be undertaken.

“We have only once before heard of the Equal Temperament Committee — a long while ago — and we were, and are still, vague as to its aims,” noted the Musical Times. “We had imagined it to be a learned Society that met from time to time to exchange light and airy chat about ratios, partials, mesotonics, and other temperamental details. But it seems that it is a body with a Mission, though we are not clear what that Mission is. Judging from the Bow Street evidence, the Committee’s aim is to make ‘Every Musician His Own Tuner’ — which seems rather rough on real tuners.”