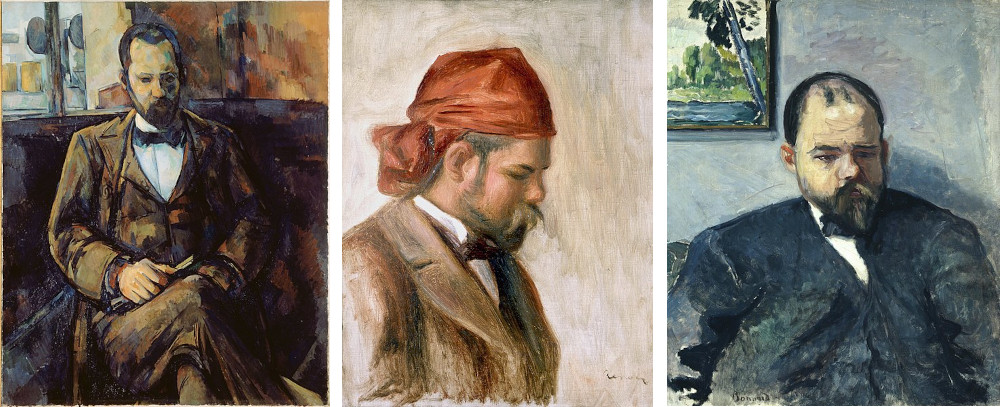

Art dealer Ambroise Vollard was acquainted with many of the foremost artists of the early 20th century, and as a result he appears often in their work. Above are portraits by Cézanne, Renoir, and Bonnard, and he sat also for Rouault, Forain, Vallotton, Bernard, and Picasso.

Picasso wrote, “The most beautiful woman who ever lived never had her portrait painted, drawn, or engraved any oftener than Vollard.”