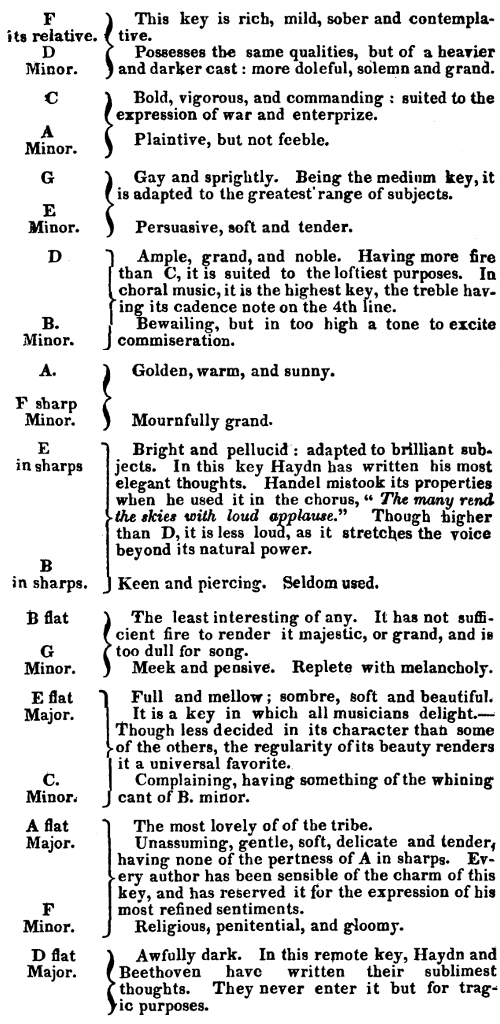

In his Musical Biography of 1824, John R. Parker attempts to characterize musical keys in words:

“It is sufficient to have hinted at these effects,” he writes. “To account for them, is difficult; but every musician is sensible of their existence.”

In his Musical Biography of 1824, John R. Parker attempts to characterize musical keys in words:

“It is sufficient to have hinted at these effects,” he writes. “To account for them, is difficult; but every musician is sensible of their existence.”

Painted on the east side of the Lani Nalu Plaza building in Honolulu, trompe-l’oeil artist John Pugh’s mural Mana Nalu (Power of the Wave) depicts Liliuokalani, the last monarch of the Hawaiian Islands, and surfing pioneer Duke Kahanamoku.

Pugh took a year and a half to create the image, working with 14 other artists. The whole scene is painted, including the wave, the skylight, the balcony, the urns, the children, and the staircase.

“After the mural was near completion,” Pugh writes, “a fire truck with crew stopped in the middle of traffic and jumped out to rescue the children in the mural. They got about 15 feet away and then doubled over laughing that they were fooled into an emergency response mode. I don’t think that there were any liability issues for a false report.”

More of Pugh’s work here and on his website.

(Thanks, Ron.)

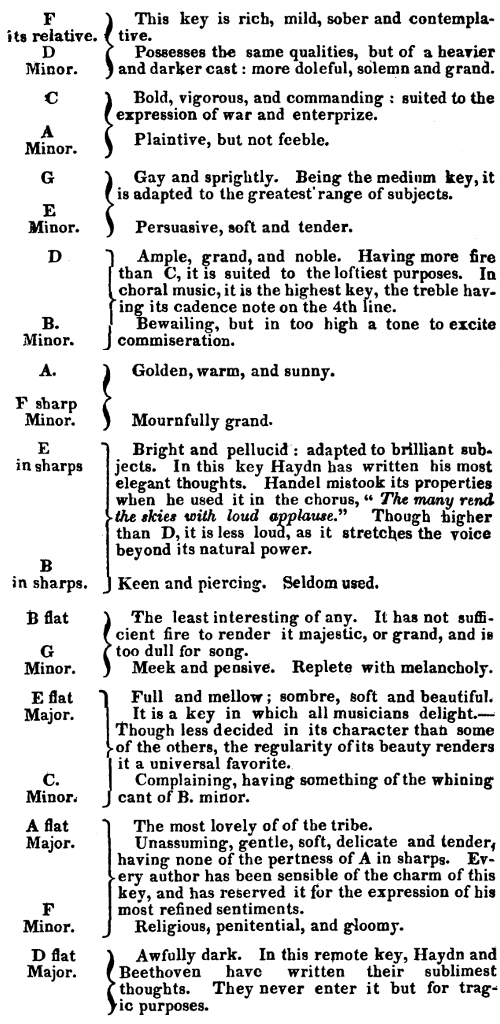

The minuet in Haydn’s Piano Sonata in A Major (Landon 41) is a palindrome. So is the trio that follows it.

The composer was so proud of his feat that he labeled the minuet Menuetto al Rovescio (“Minuet in Reverse”) and used it again in his Sonata No. 4 for Piano and Violin and his Symphony No. 47 in G major, “The Palindrome.”

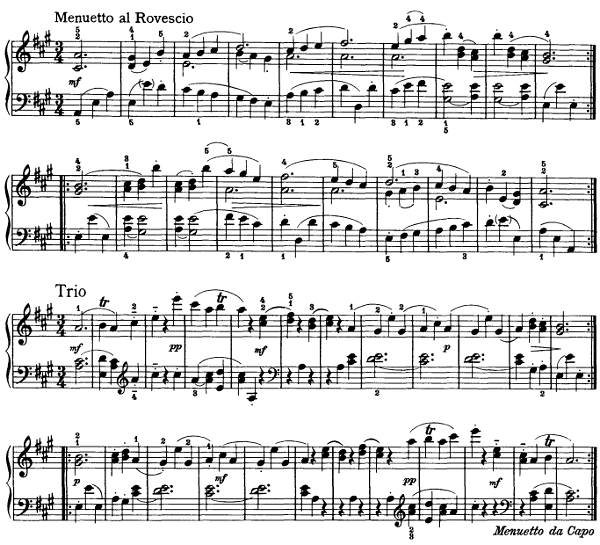

The Viking 1 orbiter brought some surprised attention to the Cydonia region of Mars in 1976 when its cameras discovered what appeared to be an enigmatic face staring up into the heavens.

The “face on Mars” has since been explained as an optical illusion, but it recalls a project conceived 30 years earlier by the American artist Isamu Noguchi. Sculpture to Be Seen From Mars, below, was proposed as a massive earthwork to be constructed in “some unwanted area,” perhaps a desert, at an enormous scale, so that the nose would be 1 mile long. When seen from space, the face would show that a civilized life form had once existed on Earth. Noguchi had been embittered by his experiences as a Japanese-American during World War II and the development of atomic weapons; he had originally called the piece Memorial to Man.

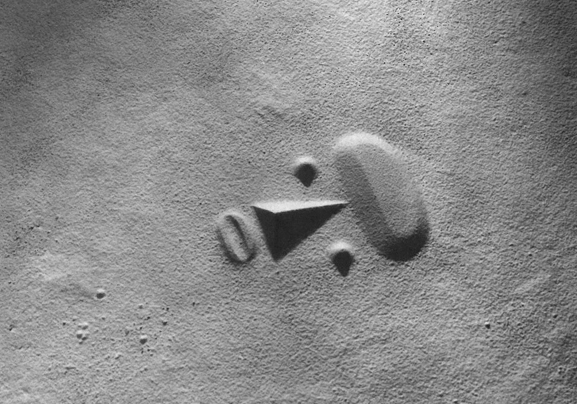

If those two don’t have enough to talk about, there’s a newcomer to join them: In 2013, face recognition software discovered the image below in a photo of the moon’s south pole taken by NASA’s Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter. Who’s next?

When M.R. James’ Ghost Stories of an Antiquary appeared in 1904, readers were puzzled to find that it contained only four illustrations, an odd number for a book of eight stories. In the preface, James explained that he’d assembled the collection at the suggestion of a friend who had offered to illustrate it but was “taken away” unexpectedly after completing only four pictures.

The friend was James McBryde, a student whom James had met in 1893 at King’s College, Cambridge, where James was dean. The two quickly became close, and McBryde was one of the select few to whom James would read a new ghost story each Christmas by the light of a single candle. They remained close after McBryde left Cambridge, traveling together each year to Denmark and Sweden, and eventually they appointed to work together to publish the ghost stories, which now numbered enough for a collection.

In May 1904 McBryde wrote, “I don’t think I have ever done anything I liked better than illustrating your stories. To begin with I sat down and learned advanced perspective and the laws of shadows …” Regarding the collection’s crowning horror, “Oh, Whistle, and I’ll Come to You, My Lad,” he wrote, “I have finished the Whistle ghost … I covered yards of paper to put in the moon shadows correctly and it is certainly the best thing I have ever drawn.”

Alas, McBryde died only a month later of complications following an appendix operation. James was adamant that no replacement be found, and Ghost Stories of an Antiquary was published with only four illustrations as a tribute to his friend. “Those who knew the artist will understand how much I wished to give a permanent form even to a fragment of his work,” he wrote. “Others will appreciate the fact that here a remembrance is made of one in whom many friendships centred.”

Of the true depth of their friendship, the full story will never be known. James picked roses, lilac, and honeysuckle from the Fellows Garden at King’s College and carried them with him on the train to McBryde’s funeral in Lancashire, where he dropped them into the grave after the other mourners had left. He remained friends with McBryde’s wife and legal guardian of his daughter, and he arranged for the posthumous publication of McBryde’s children’s book The Story of a Troll Hunt. In the introduction he wrote, “The intercourse of eleven years, — of late, minutely recalled, — has left no single act or word of his which I could choose to forget.”

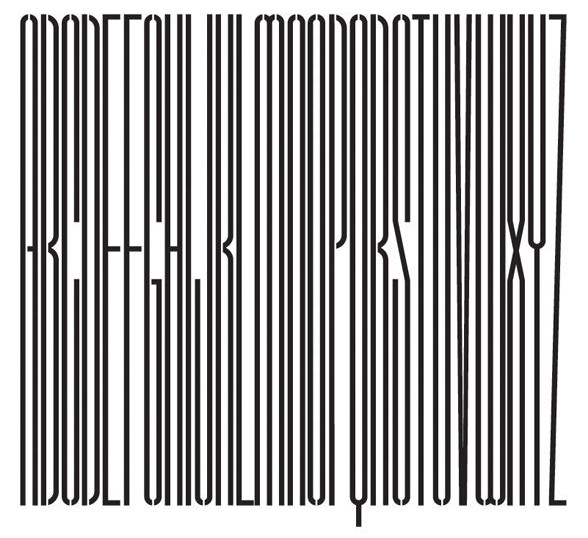

These metal gates, installed at designer Alan Fletcher’s West London studio in 1990, invite a double-take: The railings are formed from the letters of the alphabet, adapted from a condensed wood typeface of the late 19th century. The letters are mounted on two pairs of extended hinges, with the base of the Q forming the gate stop.

Reportedly local police used the gates as a landmark in orienting new recruits to the area.

You never laugh at anything nice. A comedy that ends with a laugh is a comedy that ends not with a solution but with a fresh disaster. At the end of Gogol’s The Government Inspector the real government inspector arrives; the trouble is just beginning. At the end of George F. Kaufman and Moss Hart’s Broadway comedy The Man Who Came to Dinner, the eccentric Sheridan Whiteside, who has wrought havoc in the lives of the Middle American family in whose home he is stranded by a broken ankle, walks out the door to universal relief, slips on the front step, and breaks his ankle again. According to Arthur Koestler, laughter does not truly release tension because it does not solve the problem; it fritters away energy in purposeless physical reflexes that make action impossible. Laughter is not a solution, it is a sign of the problem. As a number of writers have observed, there is a built-in contradiction between comedy’s two purposes, laughter and the happy ending. In its normal operation [the reaching of a happy ending] the function of comedy is to make the audience stop laughing.

— Alexander Leggatt, English Stage Comedy 1490-1990, 2002

Invertible Head as Basket of Fruit, c. 1590, by the Italian painter Giuseppe Arcimboldo.

He also personified the elements and the seasons.

In 1933, violinist Jelly d’Aranyi declared that the spirit of Robert Schumann was urging her to find a concerto that he’d written shortly before his death in 1856. In this episode of the Futility Closet podcast we’ll describe the discovery of Schumann’s lost violin concerto, as well as a similar case in which a London widow claimed to receive new compositions from 12 dead composers.

We’ll also puzzle over how a man earns $250,000 for going on two cruises.

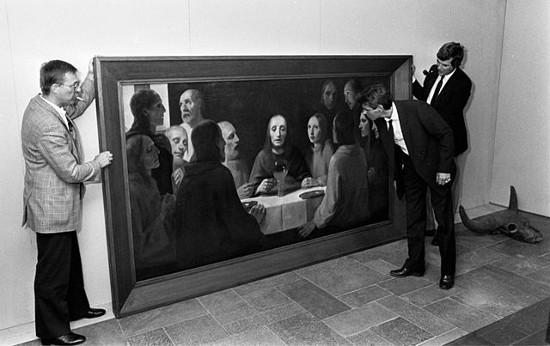

What’s the difference between forgery and plagiarism?

“This has been answered clearly by Monroe C. Beardsley: In the case of plagiarism one concerns oneself in ‘passing off another’s work as one’s own’; in the case of forgery, in ‘passing off one’s own work as another’s.'”

— Sándor Radnóti, The Fake: Forgery and Its Place in Art, 1999