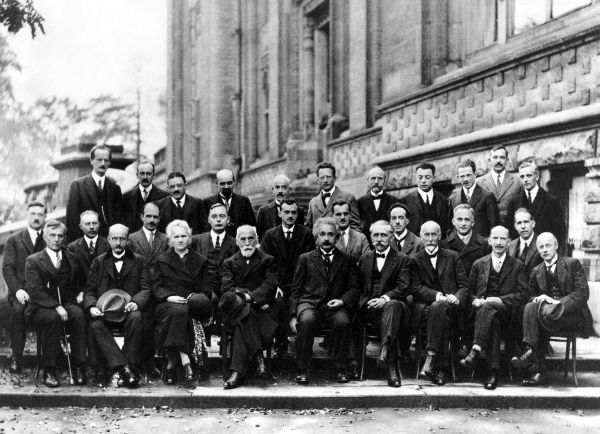

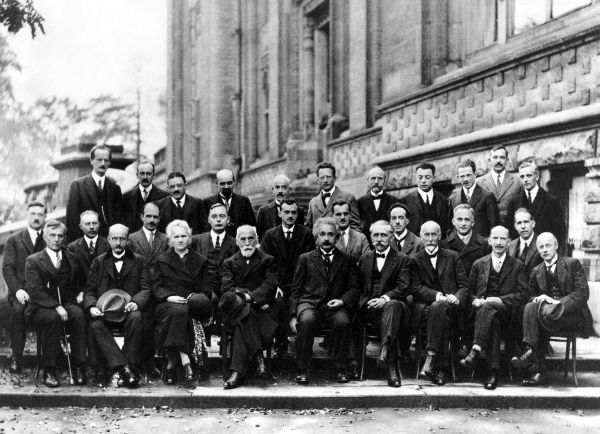

At the Fifth Solvay International Conference, held in Brussels in October 1927, 29 physicists gathered for a group photograph. Back row: Auguste Piccard, Émile Henriot, Paul Ehrenfest, Édouard Herzen, Théophile de Donder, Erwin Schrödinger, Jules-Émile Verschaffelt, Wolfgang Pauli, Werner Heisenberg, Ralph Howard Fowler, Léon Brillouin. Middle: Peter Debye, Martin Knudsen, William Lawrence Bragg, Hendrik Anthony Kramers, Paul Dirac, Arthur Compton, Louis de Broglie, Max Born, Niels Bohr. Front: Irving Langmuir, Max Planck, Marie Sklodowska Curie, Hendrik Lorentz, Albert Einstein, Paul Langevin, Charles-Eugène Guye, Charles Thomson Rees Wilson, Owen Willans Richardson.

Seventeen of the 29 were or became Nobel Prize winners. Marie Curie, the only woman, is also the only person who has won the prize in two scientific disciplines.

Below: On Aug. 12, 1958, 57 notable jazz musicians assembled for a group portrait at 17 East 126th Street in Harlem. They included Red Allen, Buster Bailey, Count Basie, Emmett Berry, Art Blakey, Lawrence Brown, Scoville Browne, Buck Clayton, Bill Crump, Vic Dickenson, Roy Eldridge, Art Farmer, Bud Freeman, Dizzy Gillespie, Tyree Glenn, Benny Golson, Sonny Greer, Johnny Griffin, Gigi Gryce, Coleman Hawkins, J.C. Heard, Jay C. Higginbotham, Milt Hinton, Chubby Jackson, Hilton Jefferson, Osie Johnson, Hank Jones, Jo Jones, Jimmy Jones, Taft Jordan, Max Kaminsky, Gene Krupa, Eddie Locke, Marian McPartland, Charles Mingus, Miff Mole, Thelonious Monk, Gerry Mulligan, Oscar Pettiford, Rudy Powell, Luckey Roberts, Sonny Rollins, Jimmy Rushing, Pee Wee Russell, Sahib Shihab, Horace Silver, Zutty Singleton, Stuff Smith, Rex Stewart, Maxine Sullivan, Joe Thomas, Wilbur Ware, Dickie Wells, George Wettling, Ernie Wilkins, Mary Lou Williams, and Lester Young. Photographer Art Kane called it “the greatest picture of that era of musicians ever taken.”