Expression markings used by Australian composer Percy Grainger:

- “Louden lots”

- “Soften bit by bit”

- “Lower notes of woggle well to the fore”

- “Glassily”

- “Sipplingly”

- “Bumpingly”

- “Hammeringly”

- “Bundling”

- “Clatteringly”

- “Like a shriek”

- “Very rhythmic and jimp”

- “Rollikingly”

- “Hold until blown”

- “Jogtrottingly”

- “Easygoingly but very clingingly”

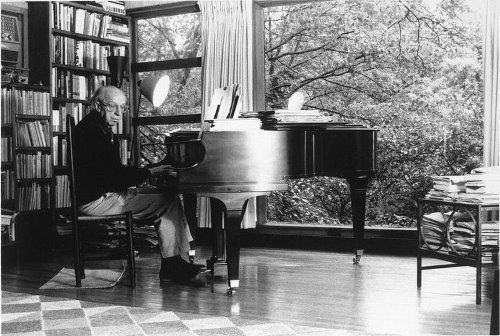

Musical directions in Erik Satie’s piano works:

- “Wonder about yourself”

- “Provide yourself with shrewdness”

- “Alone, for one moment”

- “Open the head”

- “Superstitiously”

- “In a very particular way”

- “Light as an egg”

- “Like a nightingale with a toothache”

- “Moderately, I insist”

- “A little bit warm”

- “Very Turkish”

One of Satie’s directions — “Very lost” — might have been unnecessary.