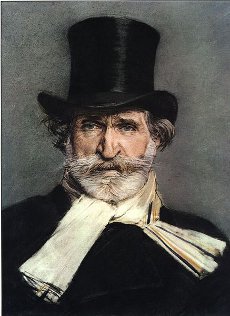

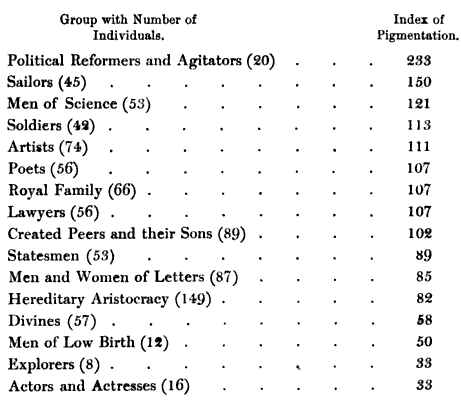

In seeking to understand how a person’s ability might vary with his complexion, Havelock Ellis chose an unusual data set: the National Portrait Gallery. Ellis spent two years examining paintings of notable Britons in various fields and established an “index of pigmentation” in each group by multiplying the number of fair people by 100 and dividing by the number of dark people. Results:

An index greater than 100 means that fair people predominate in the group; one less than 100 means that dark people predominate. The list includes both men and women.

In general, Ellis concluded, the fair man tends to be “bold, energetic, restless, and domineering,” while the dark man is “resigned and religious and imitative, yet highly intelligent.” “While the men of action thus tend to be fair, the men of thought, it seems to me, show some tendency to be dark.”

Ellis speculated that the British aristocracy tended to be dark because peers could choose the most beautiful women, and British women with the greatest reputation for beauty tended to be dark: a group of 15 English women of letters had an index of 100, while 13 famous beauties rated 44.

(“The Comparative Abilities of the Fair and the Dark,” Monthly Review, August 1901.)