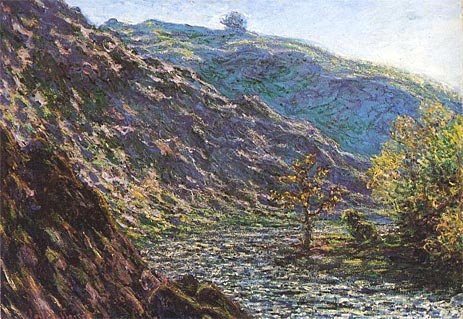

In 1889 Monet was midway through a landscape when a pivotal oak tree sprouted leaves.

He mulled this for a few days and then approached the landowner with an unusual proposition. On May 9 he wrote:

I am overjoyed — permission to remove the leaves of my beautiful oak has been graciously accorded! It was a huge job bringing large enough ladders into this ravine. Enfin, it is done, two men have been busy with it since yesterday. Isn’t it a feat to finish a winter landscape at this time of year?

In The Ultimate Irrelevant Encyclopaedia (1984), Bill Hartston remarks, “Monet makes the leaves go aground.”