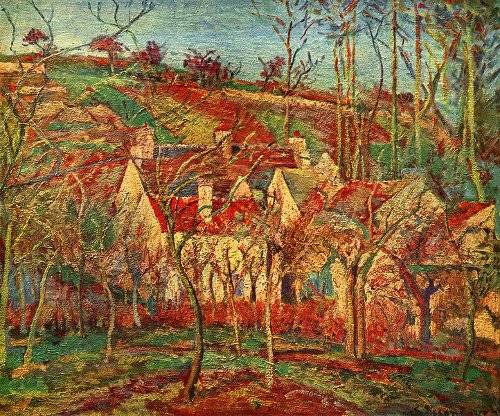

Imagine that we learned that the object before us [that] looks like a painting that would spontaneously move us if we believed it had been painted — say the Polish Rider of Rembrandt, in which an isolated mounted figure is shown midjourney to an uncertain destiny — was not painted at all but is the result of someone’s having dumped lots of paint in a centrifuge, giving the contrivance a spin, and having the result splat onto canvas, ‘just to see what would happen.’ … Now the question is whether, knowing this fact, we are prepared to consider this randomly generated object a work of art.

— Arthur Coleman Danto, The Transfiguration of the Commonplace, 1981