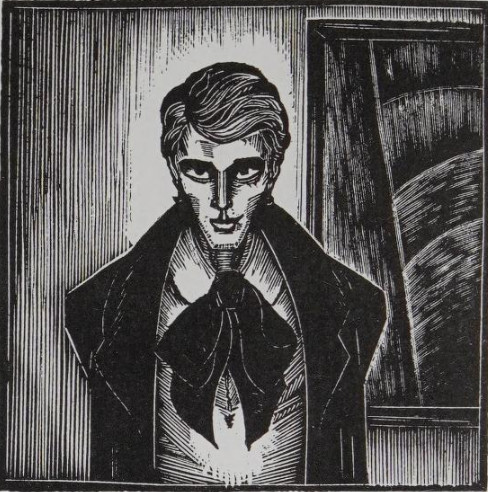

Subtitled “A Novel in Woodcuts,” Lynd Ward’s 1929 parable Gods’ Man unfolds in images, making it an important forebear of the modern graphic novel. A young artist makes his way to the big city, where a masked stranger gives him a magic paintbrush. The adventures that follow remark on the roles of love and commerce in an artist’s life; in the end the stranger returns to claim a reward.

Despite its unusual format, Ward’s book sold more than 20,000 copies during the Depression, and he followed it up with five more wordless novels. When he died in 1985, he was at work on an ambitious seventh, which Rutgers published in 2001.