“There is only one difference between a madman and me. I am not mad.” — Salvador Dali

“There is only one difference between a madman and me. I am not mad.” — Salvador Dali

Anonymous German picture puzzle, 19th century.

Draw your own conclusions.

Dick Termes paints murals on spheres. And he does it with a unique “six-point” perspective technique that permits a remarkable optical illusion.

As you watch this video, try to convince yourself that the front half of the sphere is transparent and that the mural is painted on the concave interior of the farther side — that is, that you’re standing in the center of the pictured room and turning in place to your left. If you succeed, the spin will seem to reverse direction and you’ll find yourself inside the painting:

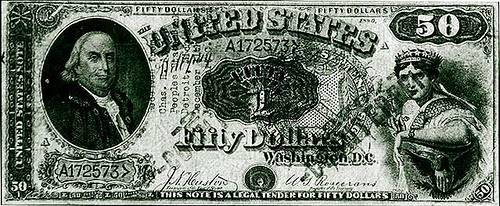

Counterfeiting was a lot harder in the old days.

In the 1880s, Emanuel Ninger, known as “Jim the Penman,” drew $50 and $100 bills by hand, spending weeks on each one. Fifty bucks was a lot back then, about $2,000 in today’s money, so the effort was worthwhile. This also meant that his “work” ended up in the hands of rich people, and he actually gained a perverse following who realized the forgeries’ value as works of art.

He drew this note in 1896, just before the Secret Service nabbed him. He’d left a note on a wet bar, and the bartender saw the ink run. Ninger served six months and was forced to pay restitution of $1. He never forged again.

Detail from The Magpie on the Gallows, by Pieter Bruegel the Elder.

Actually, you’d be hard pressed to build such a gallows — compare its top to its bottom.

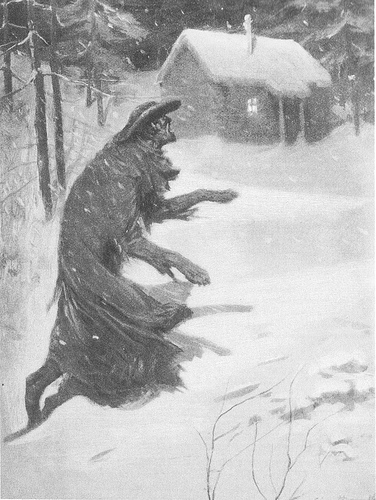

Werewolf Returning Home, a 1901 illustration by S.H. Vedder.

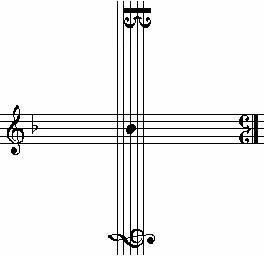

Bach’s name forms a musical motif. The German note B is equivalent to the English B-flat, and H indicates B natural. So if you revolve this cross counterclockwise, the note at the center takes successively the German values B (treble clef), A (tenor clef), C (alto clef), and H (treble clef).

Bach himself used the four-note motif as a subject in The Art of Fugue, and it’s appeared since in works by Schumann, Liszt, Rimsky-Korsakov, Poulenc, and Webern.

In 1991 Harvard’s music library discovered a lost canon of Mozart, the composer who Leonard Bernstein said offers “the spirit of compassion, of universal love, even of suffering — a spirit that knows no age, that belongs to all ages.”

It’s called “Lick Me in the Ass.”

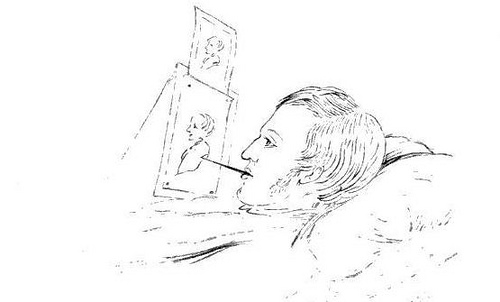

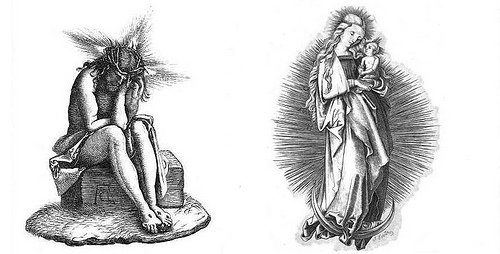

Paralyzed in a fall in 1836, John Carter discovered a talent for art, holding a brush in his teeth and working in bed. The figures below are after Albrecht Dürer.

See also No Handicap, Sarah Biffen, and Prince Randian.

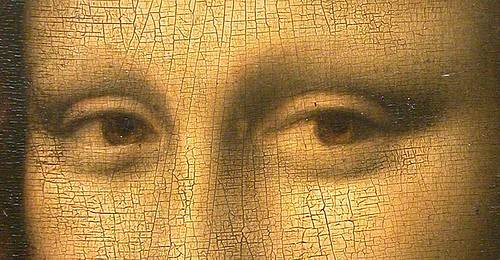

The Mona Lisa has no eyebrows.