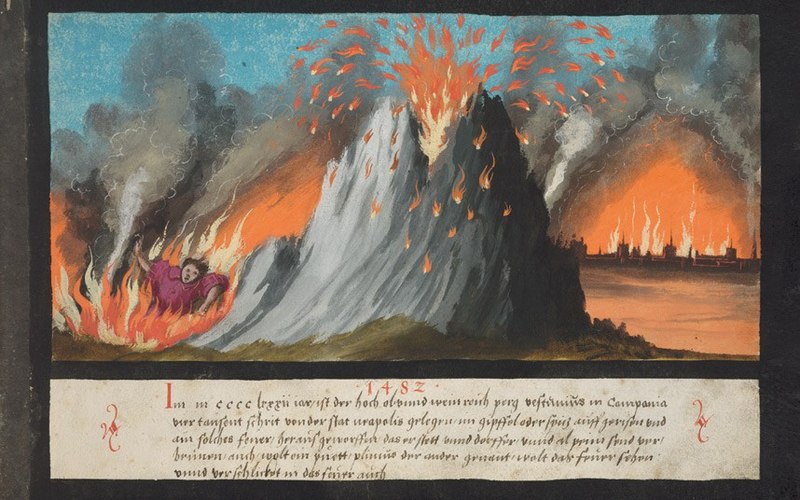

What is this? A mysterious illuminated manuscript seems to have appeared in Augsburg, Germany, around 1550, but no one knows who created it or for whom. The name of Augsburg printmaker Hans Burgkmair appears on one page, so he’s thought to be a contributor, but the manuscript contains no introduction, title page, table of contents, or dedication; instead it launches directly into a catalog of divine wonders and marvels of nature, each illustrated in full color.

“The manuscript is something of a prodigy in itself, it must be said,” wrote Marina Warner in the New York Review of Books in 2014. “[I]ts existence was hitherto unknown, and silence wraps its discovery; apart from the attribution to Augsburg, little is certain about the possible workshop, or the patron for whom such a splendid sequence of pictures might have been created.” Here it is.