In June 1946, 44-year-old Fern Bowden filed for divorce from her husband James, charging him with “cruel and inhuman treatment” and asking $100 a month to support their two teenage daughters. James filed an answer denying the charges and accusing his wife of keeping company with other men while he had been in Alaska on war business.

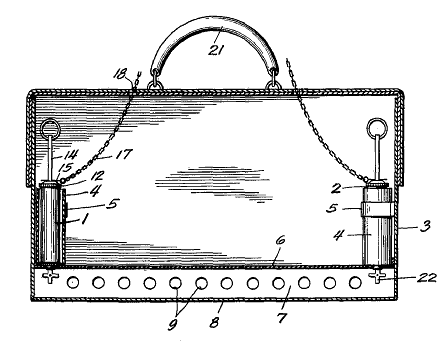

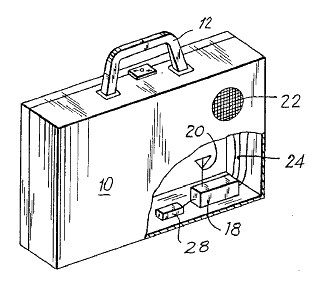

In mid-July, James began working with a small trunk which he kept locked in the basement of their Oregon home. He refused to tell the family what it contained but warned them repeatedly not to try to open it; when the girls came upon their father working on it he shouted at them to get out. Only he and their mother, he said, had the padlock combination.

On July 27, alone at home, Fern opened the box. “The cellar of the Bowden residence was wrecked by the explosion,” reported the Associated Press. “Small pieces of flesh and bone found scattered throughout the shattered parts of the home have been identified by the police criminal laboratory as human.”

Detectives determined that the trunk had contained six sticks of dynamite rigged with tacks, wire, and a small battery.

James was charged with illegal possession of explosives and first-degree murder.