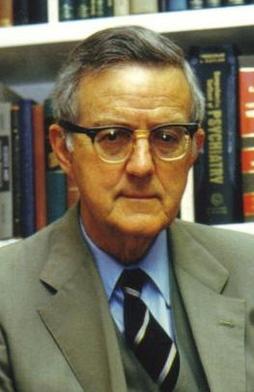

As Washington State University anthropologist Grover Krantz was dying of pancreatic cancer, he told his colleague David Hunt of the Smithsonian:

“I’ve been a teacher all my life and I think I might as well be a teacher after I’m dead, so why don’t I just give you my body.”

When Hunt agreed, Krantz added, “But there’s one catch: You have to keep my dogs with me.”

Accordingly, in 2003, Krantz’s skeleton was laid to rest in a green cabinet at the National Museum of Natural History alongside the bones of his Irish wolfhounds Clyde, Icky, and Yahoo.

Krantz’s bones have been used to teach forensics and advanced osteology to students at George Washington University.

And in 2009 his skeleton was articulated and, along with Clyde’s, displayed in the exhibition “Written in Bone: Forensic Files of the 17th Century Chesapeake.”