“I have seen a thousand graves opened, and always perceived that whatever was gone, the teeth and the hair remained of those who had died with them. Is this not odd? They go the very first things in youth and yet last the longest in the dust.” — Lord Byron, letter to John Murray, Nov. 18, 1820

Death

Podcast Episode 72: The Strange Misadventures of Famous Corpses

What do René Descartes, Joseph Haydn, and Oliver Cromwell have in common? All three lost their heads after death. In this week’s episode of the Futility Closet podcast, we’ll run down a list of notable corpses whose parts have gone wandering.

We’ll also hear readers chime in on John Lennon, knitting, diaries and Hitchcock, and puzzle over why a pilot would choose to land in a field of grazing livestock.

Working Late

Jack London died in 1916, but he turned up, gamely, in 1920 when psychic Margaret More Oliver tried to reach him through automatic writing. “I am at last attuned to life,” he wrote. “There is no discord — no conflict — the clash of mind and will with heart and impulse of soul has ended.”

She proposed that he write a story through her, and after many false starts they succeeded. “I am getting it over!” he wrote. “I am jubilant! Oh, God! it’s good to be able to do it. My pen is coming back to earth and I shall do wonders yet.”

She sent the manuscript to London’s widow, Charmian, proposing to publish it as “Death’s Sting, by Jack London, Deceased.” But Charmian refused: “If I allowed a book to come out under such ‘authorship,’ immediately every faker in the land — and they are legion — would have perfect right to do the same … the selling value of bona fide work of Jack London’s would be more or less injured, and too much depends on this.”

Oliver pressed her, but Charmian was adamant: “If I should ever be convinced, beyond the flutter of a doubt, I’d eat cyanide of potassium so quickly that I’d be on the Other Side, groping around for Jack, before I had time to think about it!”

The text of Death’s Sting seems to have been lost, but evidently it wasn’t very good — Charmian’s aunt, Netta Payne, wrote, “It has no touch of literary merit, no hint of power or idealistic beauty. It is a tedious detail of sordid facts without the least alleviation of literary artistry.” London’s spirit finally agreed: “I tried to speak with my old tongue, but my old tongue is silenced.”

One person who wasn’t surprised at any of this was Arthur Conan Doyle, who had written to Charmian a year after London’s death to suggest that “a strong soul dying prematurely with many earth interests in its thoughts, would be very likely to come back.”

“Mrs. London received my intrusion with courtesy,” Doyle wrote, “but I am not aware that any practical steps were taken toward this end. They seem now to have come from the other side.”

(Edward Biron Payne, The Soul of Jack London, 1927.)

Podcast Episode 67: Composing Beyond the Grave

In 1933, violinist Jelly d’Aranyi declared that the spirit of Robert Schumann was urging her to find a concerto that he’d written shortly before his death in 1856. In this episode of the Futility Closet podcast we’ll describe the discovery of Schumann’s lost violin concerto, as well as a similar case in which a London widow claimed to receive new compositions from 12 dead composers.

We’ll also puzzle over how a man earns $250,000 for going on two cruises.

The Hasanlu Lovers

In 1972, archaeologists unearthed a plaster-lined brick bin in the Teppe Hasanlu site in northwestern Iran, an ancient city that had been violently sacked and burned at the end of the ninth century B.C. University of Pennsylvania archaeologist Robert Dyson wrote:

Lying in the bottom of the bin were two human skeletons, a male and a female. The male had one of its arms under the shoulder of the female, while the female was looking into the face of the male and reaching out with one hand to touch his lips. Both were young adults. Neither showed any evidence of injury; there were no obvious cuts or broken bones. There were no objects with the skeletons, but under the female’s head was a stone slab. The other contents of the bin consisted of broken pieces of plaster, charcoal, and small pieces of burned brick but nothing heavy enough to crush the bones.

“Two theories have been suggested to explain this unusual scene,” he wrote. “One, that a pair of lovers had crawled into the bin under some light material of some kind to hide in the hope of escaping the destruction of the citadel, and that this is a very tender moment between them. The other is that they were hiding and one is telling the other not to make any noise. In either case it would appear they died peacefully — probably by asphyxiation.”

The Death Mask Stamps

In 1903 Serbian king Alexander I and his queen were murdered in their palace. Alexander’s successor, Peter Karageorgevich, rescinded postage stamps bearing the dead king’s portrait and marked his own coronation with this stamp, depicting twin profiles of himself and his ancestor Black George, a Serbian patriot:

If he’d hoped this would allay suspicion, he was mistaken. In Through Savage Europe (1907), writer Harry De Windt notes that when the stamp is turned upside down, “the gashed and ghastly features of the murdered King stand out with unmistakable clearness”:

That’s a bit overstated. Here’s Alexander’s original stamp and the purported “death mask” — gaze at it blankly and Alexander’s features will emerge from the noses, brows, and chins:

“Needless to state, the issue was at once prohibited.”

Rehearsal

In 1940, just before the release of her film They Knew What They Wanted, Carole Lombard’s press agent, Russell Birdwell, approached the filmmakers with a novel publicity scheme. Lombard would be scheduled to fly to New York for the opening, but they would arrange for the plane to “go down” en route and remain missing for 12 hours.

“And in those twelve hours, fellas, we’re going to be on every goddam front page in the United States of America,” Birdwell said. “Not only Carole Lombard’s name, but the name of the picture and the name of the theatre it’s going to open at and how would you like to foot the bill for that kind of advertising?” He planned that eventually Lombard and the pilot could wander out of the woods saying that the plane’s engines and radio had died.

In his 1967 memoir Hollywood, director Garson Kanin remembers that in the meeting Lombard began to slap her thigh, yelling, “I’ll die! I’ll die! Isn’t that something? I’ll die!”

Birdwell’s plan was considered seriously but finally canceled due to the cost. Two years later, Lombard died in a plane crash in Nevada. “I could hear Carole’s voice and the sound of her hand slapping her thigh, her voice yelling delightedly, ‘I’ll die! I’ll die!'” Kanin wrote. “I remembered Russell Birdwell’s notion of the fake crash for publicity. I stood there hoping against hope that perhaps this was a postponed version of his scheme. … Carole Lombard … could not be dead at thirty-five. But she was.”

(Thanks, Ted.)

Last Words

Amelia Earhart left behind what she called “popping off letters,” to be opened in the event of her death. This one, discovered by her husband and biographer, George Putnam, was addressed to her father:

May 20, 1928

Dearest Dad:

Hooray for the last grand adventure! I wish I had won, but it was worth while anyway. You know that.

I have no faith we’ll meet anywhere again, but I wish we might.

Anyway, good-by and good luck to you.

Affectionately, your doter,

Mill

Another, addressed to her mother, read simply, “Even though I have lost, the adventure was worth while. Our family tends to be too secure. My life has really been very happy, and I don’t mind contemplating its end in the midst of it.”

A Late Contribution

A ghost co-authored a mathematics paper in 1990. When Pierre Cartier edited a Festschrift in honor of Alexander Grothendieck’s 60th birthday, Robert Thomas contributed an article that was co-signed by his recently deceased friend Thomas Trobaugh. He explained:

The first author must state that his coauthor and close friend, Tom Trobaugh, quite intelligent, singularly original, and inordinately generous, killed himself consequent to endogenous depression. Ninety-four days later, in my dream, Tom’s simulacrum remarked, ‘The direct limit characterization of perfect complexes shows that they extend, just as one extends a coherent sheaf.’ Awaking with a start, I knew this idea had to be wrong, since some perfect complexes have a non-vanishing K0 obstruction to extension. I had worked on this problem for 3 years, and saw this approach to be hopeless. But Tom’s simulacrum had been so insistent, I knew he wouldn’t let me sleep undisturbed until I had worked out the argument and could point to the gap. This work quickly led to the key results of this paper. To Tom, I could have explained why he must be listed as a coauthor.

Thomason himself died suddenly five years later of diabetic shock, at age 43. Perhaps the two are working again together somewhere.

(Robert Thomason and Thomas Trobaugh, “Higher Algebraic K-Theory of Schemes and of Derived Categories,” in P. Cartier et al., eds., The Grothendieck Festschrift Volume III, 1990.)

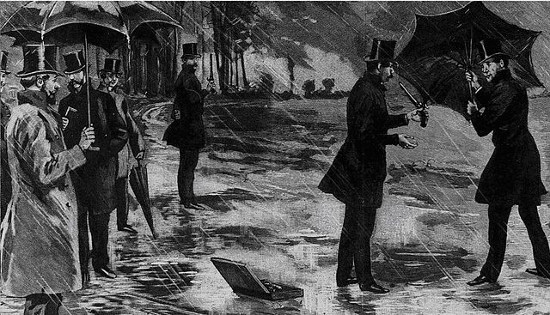

Precautions

I should have wished also to have referred to some of the serio-comic duels, such as that fought by the famous critic Sainte-Beuve against M. Dubois, of the Globe newspaper. When the adversaries arrived on the ground it was raining heavily. Sainte-Beuve had brought an umbrella and some sixteenth-century flint-lock pistols. When the signal to fire was about to be given, Sainte-Beuve still kept his umbrella open. The seconds protested, but Sainte-Beuve resisted, saying, ‘I am quite ready to be killed, but I do not wish to catch cold.’

— Theodore Child, “Duelling in Paris,” Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, March 1887