Before his death in 1923, Curtis Lloyd erected an enormous granite monument to himself in the Kentucky woods. One side reads:

CURTIS G. LLOYD BORN 1859 — DIED 60 OR MORE YEARS AFTERWARDS. THE EXACT NUMBER OF YEARS, MONTHS AND DAYS THAT HE LIVED NOBODY KNOWS AND NOBODY CARES.

The other side reads:

CURTIS G. LLOYD MONUMENT ERECTED IN 1922 BY HIMSELF FOR HIMSELF DURING HIS LIFE TO GRATIFY HIS OWN VANITY. WHAT FOOLS THESE MORTALS BE!

World War I ended at 11 a.m. on Nov. 11, 1918. Each year at that moment, sunlight shining through the window of the Canadian War Museum illuminates the headstone of Canada’s Unknown Soldier.

In Gray, Maine, is a tombstone reading:

STRANGER — A SOLDIER OF THE LATE WAR. DIED 1862. ERECTED BY THE LADIES OF GRAY.

Lt. Charles Colley of the 10th Maine Volunteers had died that September at Alexandria, Va., and his parents had paid to have his remains embalmed and transported home. When they opened the casket, they found the body of a uniformed Confederate soldier. After some consternation the town interred him, and it commemorates the unknown soldier each Memorial Day. (Colley’s body arrived a week later and is buried 100 feet away.)

An epitaph in Keesville, N.Y., quoted in John R. Kippax, Churchyard Literature, 1876:

HERE LIES A MAN OF GOOD REPUTE,

WHO WORE A NO. 16 BOOT.

‘TIS NOT RECORDED HOW HE DIED,

BUT SURE IT IS, THAT OPEN WIDE,

THE GATES OF HEAVEN MUST HAVE BEEN

TO LET SUCH MONSTROUS FEET WITHIN.

Charles Wallis’ Stories on Stone records the epitaph of Dr. Fred Roberts in Pine Log Cemetery, Brookland, Ark.:

OFFICE UP STAIRS.

An epitaph on a trout, near a pond in Blockley, England:

IN

MEMORY

OF THE

OLD FISH.

UNDER THE SOIL

THE OLD FISH DO LIE

20 YEARS HE LIVED

AND THEN DID DIE.

HE WAS SO TAME

YOU UNDERSTAND

HE WOULD COME AND

EAT OUT OF OUR HAND.

DIED APRIL 20, 1855.

AGED 20 YEARS.

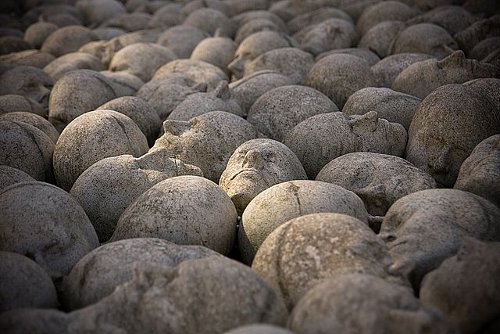

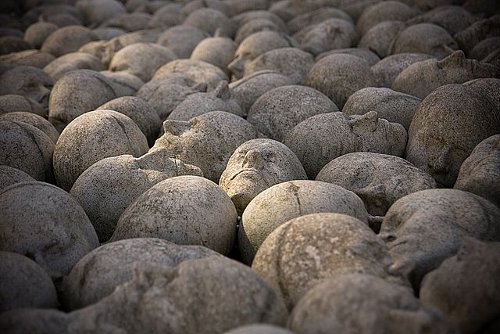

Below: The German word for cobblestone translates literally as “headstone” — so artist Timm Ulrichs offered this “cobblestone” pavement:

(Thanks, Zach.)