On New Year’s Eve 1819, 33-year-old London tea dealer Elton Hamond committed suicide. A man found guilty of deliberate self-murder would forfeit his estate, so Hamond composed this plea:

To the Coroner and the Gentlemen who will sit on my Body.

Norwood, 31st December, 1819.

Gentlemen,

To the charge of self-murder I plead not guilty. For there is no guilt in what I have done. Self-murder is a contradiction in terms. If the King who retires from his throne is guilty of high treason; if the man who takes money out of his own coffers and spends it is a thief; if he who burns his own hayrick is guilty of arson; or he who scourges himself of assault and battery, then he who throws up his own life may be guilty of murder, — if not, not.

If anything is a man’s own, it is surely his life. Far, however, be it from me to say that a man may do as he pleases with his own. Of all that he has he is a steward. Kingdoms, money, harvests, are held in trust, and so, but I think less strictly, is life itself. Life is rather the stewardship than the talent. The King who resigns his crown to one less fit to rule is guilty, though not of high treason; the spendthrift is guilty, though not of theft; the wanton burner of his hayrick is guilty, though not of arson; the suicide who could have performed the duties of his station is perhaps guilty, though not of murder, not of felony. They are all guilty of neglect of duty, and all, except the suicide, of breach of trust. But I cannot perform the duties of my station. He who wastes his life in idleness is guilty of a breach of trust; he who puts an end to it resigns his trust, — a trust that was forced upon him, — a trust which I never accepted, and probably never would have accepted. Is this felony? I smile at the ridiculous supposition. How we came by the foolish law which considers suicide as felony I don’t know; I find no warrant for it in Philosophy or Scripture. It is worthy of the times when heresy and apostacy were capital offences; when offences were tried by battle, ordeal, or expurgation; when the fine for slaying a man was so many shillings, and that for slaying an ass a few more or less.

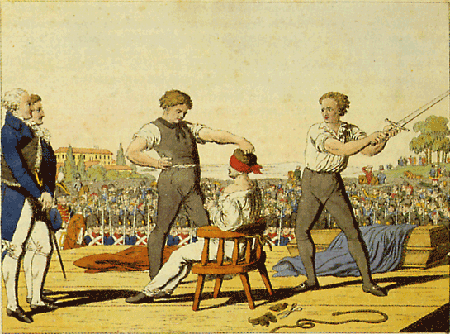

Every old institution will find its vindicators while it remains in practice. I am an enemy to all hasty reform, but so foolish a law as this should be put an end to. Does it become a jury to disregard it? For juries to disregard their oaths for the sake of justice is, as you probably know, a frequent practice. The law places them sometimes in the cruel predicament of having to choose between perjury and injustice: whether they do right to prefer perjury, as the less evil, I am not sure. I would rather be thrown naked into a hole in the road than that you should act against your consciences. But if you wish to acquit me, I cannot see that your calling my death accidental, or the effect of insanity, would be less criminal than a jury’s finding £10 Bank-of-England note worth thirty-nine shillings, or premeditated slaying in a duel simple manslaughter, both of which have been done. But should you think this too bold a course, is it less bold to find me guilty of being felo de se when I am not guilty at all, as there is no guilt in what I have done? I disdain to take advantage of my situation as culprit to mislead your understandings, but if you, in your consciences, think premeditated suicide no felony, will you, upon your oaths, convict me of felony? Let me suggest the following verdict, as combining liberal truth with justice: — ‘Died by his own hand, but not feloniously.’ If I have offended God, it is for God, not you, to enquire. Especial public duties I have none. If I have deserted any engagement in society, let the parties aggrieved consign my name to obloquy. I have for nearly seven years been disentangling myself from all my engagements, that I might at last be free to retire from life. I am free to-day, and avail myself of my liberty. I cannot be a good man, and prefer death to being a bad one, — as bad as I have been and as others are.

I take my leave of you and of my country condemning you all, yet with true honest love. What man, alive to virtue, can bear the ways of the best of you? Not I, you are wrong altogether. If a new and better light appears, seek it; in the meantime, look out for it. God bless you all!

Hamond left the letter with his friend Henry Crabb Robinson: “Mind you don’t get yourself into a scrape by making an over-zealous speech if you attend as my counsel. You may say throughout, ‘The culprit’s defence is this.'” Robinson, fearing a scandal, passed it unread to Hamond’s relations, and the jury found Hamond insane.