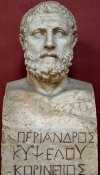

Periander ordered two young men to go out by night along a certain road, to kill the first man they met there, and to bury him.

Then he ordered four more men to find those two and kill them. And he sent an even greater number to murder those four.

Periander then set off down the road himself to wait for them.

In this way he ensured that the location of his grave would never be known.