Preparing for heart surgery at age 81, Rodney Dangerfield was asked how long he’d be in the hospital.

“If all goes well, about a week,” he said. “If not, about an hour and a half.”

Preparing for heart surgery at age 81, Rodney Dangerfield was asked how long he’d be in the hospital.

“If all goes well, about a week,” he said. “If not, about an hour and a half.”

A manuscript published at Tortona, Italy, in 1677 tells of a Milanese friar who was killed by a meteorite:

All the other monks of the convent of St. Mary hastened up to him who had been struck, as well from curiosity as from pity, and among them was also the Canon Manfredo Settala. They all carefully examined the corpse, to discover the most secret and decisive effects of the shock which had struck him; they found it was on one of the thighs, where they perceived a wound blackened either by the gangrene or by the action of the fire. Impelled by curiosity, they enlarged the aperture to examine the interior of it; they saw that it penetrated to the bone, and were much surprised to find at the bottom of the wound a roundish stone which had made it, and had killed this monk in a manner equally terrible and unexpected.

Take that for what it’s worth. In modern times meteorites have struck an Alabama woman and a Ugandan boy, but neither was seriously injured. (There’s also a dog story.)

On Aug. 12, 1985, Japan Airlines Flight 123 suffered mechanical failures after departing Tokyo. It struggled for 32 minutes to stay aloft but finally crashed into Mount Takamagahara, killing 520 people.

Among the debris was found the company diary of 52-year-old shipping manager Hirotsugu Kawaguchi. Apparently he had spent the fateful half hour composing a seven-page letter to his family:

Mariko, Tsuyoshi, Chiyoko — Please get along well with each other and help your mama. Papa feels very sorry I won’t survive. I don’t know the reason. Five minutes have passed. …

I never want to take an airplane again. Dear God, please help me. I didn’t imagine that yesterday’s dinner was going to be the last one with you all. …

Something seems to have exploded in the airplane. Smoke is coming out. … Airplane is going down. I don’t know where we are going and what is going to happen. …

Tsuyoshi — I do really count on you. Honey — I feel very sorry about what is happening to me. Goodbye. Please take care of our children. It’s six-thirty now. The airplane is spinning and going down quickly. …

I’m very thankful to you that I was able to have a really happy life up to now.

The crash remains the deadliest single-plane accident in world history.

When New York gangster Dutch Schultz was shot in 1935, police had a stenographer take down his delirious last words. Find a confession here if you can:

His final words were “I will settle the indictment. Come on, open the soap duckets. The chimney sweeps. Talk to the sword. Shut up, you got a big mouth! Please help me up, Henry. Max, come over here. French-Canadian bean soup. I want to pay. Let them leave me alone.”

Some kings expire in bed. Some die gloriously in battle.

Alexander of Greece was bitten to death by monkeys.

He was walking in the royal garden in October 1920 when a monkey attacked his dog. He fought it off with a stick, suffering only a wound on the hand, but the monkey’s mate rushed in and gave him a much more severe bite. He died of blood poisoning three weeks later.

Alexander’s exiled father returned and led the nation into a bloody war with Turkey. “It is perhaps no exaggeration,” wrote Winston Churchill, “to remark that a quarter of a million persons died of this monkey’s bite.”

A building curiously arranged to resemble the hull of a ship, the rooms of which were made to look like its cabins, used to be pointed out for many years in Wandsworth. Upon the top of it a small room, or rather turret, used to attract special attention, for it contained the corpse of its builder and former owner, an eccentric old sailor, whose will made it a condition of inheritance that his body should be buried on what he called ‘the deck’ of his ship-house. The house was pulled down by a railway company about 1860.

— The World of Wonders, 1883

Epitaph on a Florentine tombstone of 1318:

Here lies Salvino Armolo D’Armati,

of Florence,

the inventor of spectacles.

May God pardon his sins!

From Walter Henry Howe, “Here Lies,” 1900

At Bradford, England, a girl, aged 16, met death in an extraordinary manner. While in the playground of her school she was caught by a veritable tornado which carried her into the air. … [A] witness who was waiting for a car in front of the school said he saw the girl in the air, her skirts blown out like a baloon. She was 25 to 30 feet in the air, just above the school balcony (the latter, the coroner remarked, was 20 feet high). … The physician who was called found the girl unconscious and pulseless, suffering from severe concussion of the brain and compound fractures of the lower jaw, right arm, wrist and thigh. It appeared that she was wearing a pair of bloomers with an ordinary skirt but without petticoats. The jury returned a verdict of ‘died as the result of a fall caused by a sudden gust of wind.’

— Journal of the American Medical Association, quoted in Medical Sentinel, June 1911

05/24/2010 I’ve found some confirmation of this in William Corliss, Tornados, Dark Days, Anomalous Precipitation, 1983:

“February 25, 1911. Bradford, England. A letter to the editor called the report of a girl being killed by a gust of wind preposterous and asked for an investigation. The editor replied: ‘Acting on this suggestion, we communicated with Mr. H. Lander, the rainfall observer at Lister Park, Bradford, who kindly sent us a copy of the Yorkshire Observer for February 25th, in which there was a fairly full report of the inquest on the school-girl who was undoubtedly killed by a fall from a great height in an extremely exposed playground during very gusty weather. One witness saw the girl enter the playground from the school at 8.40 a.m., and saw her carried in three minutes later. Another witness saw the girl in the air parallel with the balcony of the school 20 feet above the ground, her arms extended, and her skirts blown out like a balloon. He saw her fall with a crash. The jury found a verdict, ‘Died as the result of a fall caused by a sudden gust of wind.'”

He cites Godden, William; “The Tale of — a Gust,” Symons’s Meteorological Magazine, 46:54, 1911.

Spiritualist Ludwig von Guldenstubbe had a no-nonsense approach to communicating with the dead — he left paper and pencil for them in Paris churches and cemeteries.

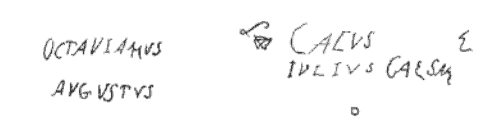

He got only a few scrawls at first, but apparently word spread through the underworld, and soon more illustrious correspondents turned up. In August 1856 von Guldenstubbe produced the signatures of the emperor Augustus and of Julius Caesar, collected at their statues in the Louvre:

He also received writings from Abélard, who wrote in bad Latin, and Héloïse, in modern French — evidently she’s been taking correspondence courses since the 12th century.

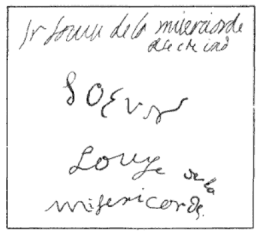

Sadly, it appears that death spoils one’s penmanship — here are writing samples from Louise de La Vallière, the repentant mistress of Louis XIV, before (top) and after dying:

Perhaps that’s understandable, given the circumstances.

In the 10 months between August 1856 and June 1857, von Guldenstubbe says he got more than 500 specimens this way, in the company of more than 50 witnesses — but somehow no one has ever duplicated his results.

Most graves in Massachusetts’ Stockbridge Cemetery are oriented with the feet facing east, so that on Resurrection Day the dead will rise facing Jerusalem.

Not so the Sedgwick family — patriarch Theodore Sedgwick ordered that his family’s graves form a circle with their feet toward the center. This way, on Judgment Day, Sedgwicks will see only other Sedgwicks.

It’s been called “the laughingstock of the entire Eastern seaboard.”