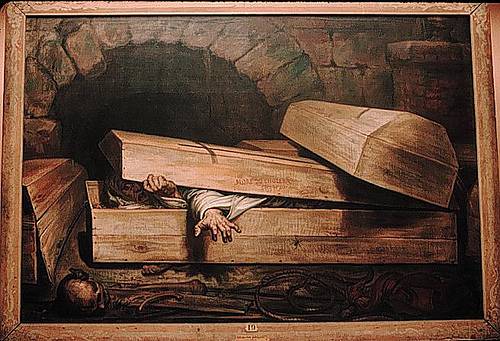

Excerpt from the will of Joseph Dalby, London, 1784:

I give to my daughter Ann Spencer, a guinea for a ring, or any other bauble she may like better: — I give to the lout, her husband, one penny, to buy him a lark-whistle; I also give to her said husband, of redoubtable memory, my fart-hole, for a covering for his lark-whistle, to prevent the abrasion of his lips; and this legacy I give him as a mark of my approbation of his prowess and nice honour, in drawing his sword on me, (at my own table), naked and unarmed as I was, and he well fortified with custard.