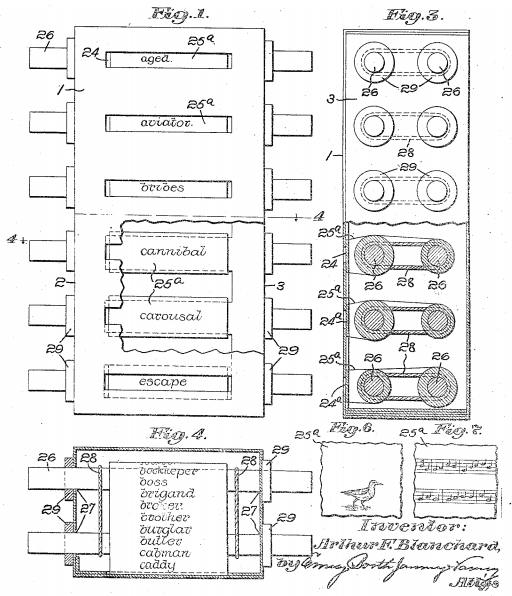

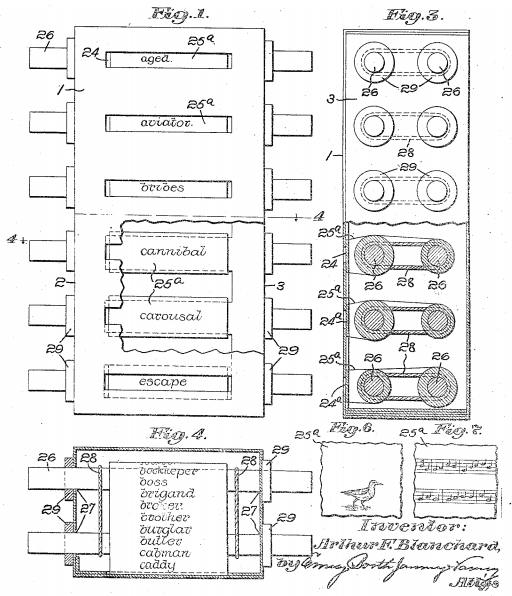

Here’s a curious invention from 1916, in the early days of motion pictures: It’s a machine designed to suggest plot ideas by randomly juxtaposing ideas. Words, pictures, and even bars of music are printed on paper rollers, and the writer turns these to present six elements that form the basis of a story.

In the example above, the machine presents the words aged, aviator, bribes, cannibal, carousal, and escape. “These particular words readily suggest, for instance, that an aged aviator after flying through the air on a long trip, lands finally on a desolate island where he is met by a cannibal, whom he is forced to bribe to secure his safety. After an interim which is full of possibilities as a basis of a story, a carousal ensues following which the aviator escapes.”

Inventor Arthur Blanchard says that this technique can be used to inspire any fictional work, from a cartoon to a song, but he patented it specifically as a “movie writer.” Whether it inspired any movies I don’t know.