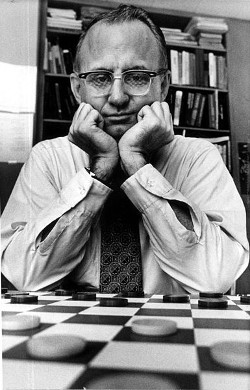

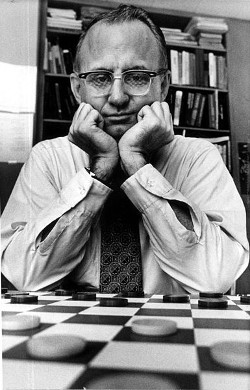

Mathematician Marion Tinsley lost only seven games of checkers in a career that spanned 45 years. Between 1950 and 1995, he took first place in every tournament in which he played. “Dr. Tinsley has taken the game beyond what anybody else ever conceived,” International Checkers Hall of Fame founder Charles Walker told Sports Illustrated in 1992. “No one presumed to think they could beat him.”

His last and best opponent was a machine, Chinook, designed by University of Alberta computer scientist Jonathan Schaeffer. When the American Checkers Federation refused to let a machine play for the championship in 1990, the sporting Tinsley resigned his crown and immediately accepted the match.

He won 4-2, with 33 draws. In one game, after the program had played its 10th move, Tinsley said, “You’re going to regret that.” Chinook resigned 26 moves later, and in the ensuing analysis Schaeffer found that Tinsley had looked 64 moves ahead to find the only winning strategy. (When asked for the source of his advantage, Tinsley, a lay preacher, said, “I’ve got a better programmer — God.”)

But the machine kept improving, and Tinsley’s health began to fail. He had to withdraw after six draws in their 1994 rematch, and he died of pancreatic cancer shortly afterward at age 68.

Chinook has since solved the game — after 18 years of thinking, it produced a map that would show it a non-losing move in any situation. In principle, at least, the computer is now invincible — the best a human can hope for is a draw.

This might have disappointed Tinsley, who played not for supremacy but for a love of the game. “Checkers can get quite a hold on you,” he said. “Its beauty is just overwhelming — the mathematics, the elegance, the precision. It’s capable of wrapping you all up.”