In 1961, when Groucho Marx turned 71, he received a telegram from Irving Berlin:

THE WORLD WOULD NOT BE IN SUCH A SNARL

HAD MARX BEEN GROUCHO INSTEAD OF KARL.

In 1961, when Groucho Marx turned 71, he received a telegram from Irving Berlin:

THE WORLD WOULD NOT BE IN SUCH A SNARL

HAD MARX BEEN GROUCHO INSTEAD OF KARL.

The word zombie is never used in Night of the Living Dead.

The word Mafia is never used in The Godfather.

It is often very hard to tell a fake from an original, even when you know it must be fake. Think about the opening scenes of the movie version of Dan Brown’s The Da Vinci Code. Some scenes were shot in the galleries of the Louvre. The museum would not allow actors Tom Hanks or Audrey Tautou to remove Leonardos from the wall, so those scenes were shot in London. One hundred and fifty paintings from the Louvre were reproduced for the London set, using digital photography. Artist James Gemmill overpainted and glazed each, even copying the craquelure and the wormholes in the frames. When Madonna of the Rocks is removed from the wall, the back of the painting shows the correct stretcher placement and Louvre identification codes.

Dealers in Old Masters who saw the movie and were familiar with the originals in the Louvre confess to not being sure which paintings are copies … The answer is that every painting in the movie that is touched by Hanks or Tautou is a copy. Paintings that appear only as background in the Louvre are real. What happened to James Gemmill’s copies after the scenes were shot? No one will say.

— Don Thompson, The $12 Million Stuffed Shark, 2009

One afternoon the doorbell rang at Peter Sellers’ London flat. Sellers was working in his study upstairs, so his wife Anne answered the door. It was a telegram for her:

BRING ME A CUP OF COFFEE. PETER.

In 1960 Jerry Lewis and Henny Youngman were having lunch at a Miami restaurant when Lewis was mobbed by autograph seekers. Youngman slipped out to the lobby unnoticed and returned as if nothing had happened. Shortly afterward Lewis received a telegram from the hotel bellboy:

DEAR JERRY, PLEASE PASS THE SALT. HENNY.

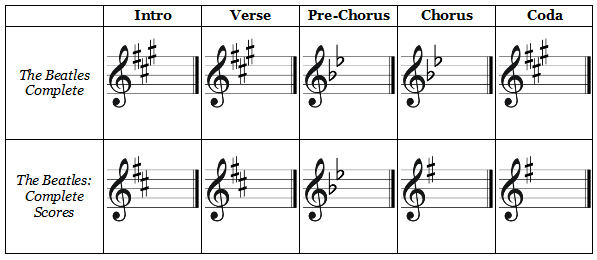

What key is “Lucy in the Sky With Diamonds” written in? It’s not easy to say; the harmony is strangely ambiguous. Musicologist Naphtali Wagner found that the song is notated differently in two reasonably authoritative sources, Wise Publications’ The Beatles Complete (1983) and Hal Leonard’s The Beatles: Complete Scores (1993):

And he found that scholars disagree as well:

Wagner shows that a case can be made for three rival interpretations: A major, D major, and G major. “Each is consistent with the Beatles’ harmonic style and has precedents in many other songs.” But he adds that one solution might be to abandon the idea of monotonality and see the song as oscillating between two keys: A in the chorus and pre-chorus and G in the chorus. “This version could be defended with the argument that oscillation between tonal centres separated by a major second is found in other Beatles songs, such as ‘Doctor Robert,’ ‘Good Day Sunshine’ and ‘Penny Lane.'”

(Naphtali Wagner, “The Beatles’ Psycheclassical Synthesis: Psychedelic Classicism and Classical Psychedelia in Sgt. Pepper,” in Oliver Julien, ed., Sgt. Pepper and the Beatles, 2008.)

Six countries have names that begin with the letter K, and each has a different vowel as the second letter: Kazakhstan, Kenya, Kiribati, Kosovo, Kuwait, Kyrgyzstan.

(Thanks, Danny.)

Masaoka Shiki, the fourth of Japan’s great haiku masters, is a member of the Japanese Baseball Hall of Fame. Described as “baseball mad,” Shiki first encountered the game in preparatory school in 1884, only 12 years after American teacher Horace Wilson first introduced it to his students at Tokyo University in 1872. Shiki wrote nine baseball haiku, the first in 1890, making him the first Japanese writer to use the game as a literary subject:

spring breeze

this grassy field makes me

want to play catch

like young cats

still ignorant of love

we play with a ball

the trick

to ball catching

the willow in a breeze

Throughout his career Shiki wrote essays, fiction, and poetry about the game, and he made translations of baseball terms that are still in use today. Eventually he taught the game to Kawahigashi Hekigotō and Takahama Kyoshi, who themselves became famous haiku poets under his tutelage, and today a baseball field near Bunka Kaikan in Ueno bears his name. He wrote:

under a faraway sky

the people of America

began baseball

I can watch it

forever

“When you come to the evolution of the dance, its history and philosophy, I know as much about that as I do about how a television tube produces a picture — which is absolutely nothing. I don’t know how it all started and I don’t want to know. I have no desire to prove anything by it. I have never used it as an outlet or as a means of expressing myself. I just dance.” — Fred Astaire

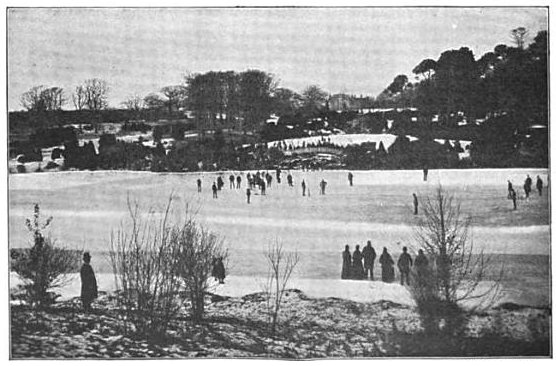

From the London Review and Literary Journal of August 1796:

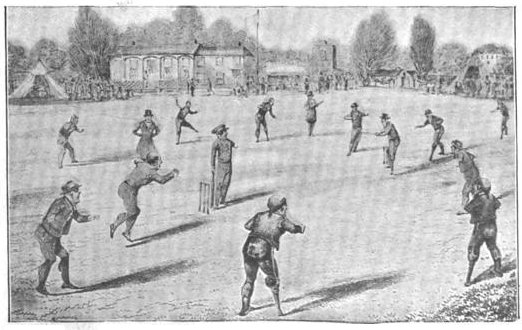

A Cricket-Match was played by eleven Greenwich Pensioners with one leg against eleven with one arm, for one thousand guineas, at the new Cricket ground, Montpelier Gardens, Walworth. About nine o’clock the men arrived in three Greenwich stages; about twelve the wickets were pitched, and the matched commenced. Those with but one leg had the first innings, and got ninety-three runs; those with but one arm got but forty-two runs during their innings. The one-legs commenced their second innings, and six were bowled out after they got sixty runs, so that they left off one hundred and eleven more than those with one arm. Next morning the match was played out, and the men with one leg beat the one-arms by 103 runnings. After the match was finished, the eleven one-legged men run a sweepstakes of one hundred yards distance, for twenty guineas, and the three first had prizes.

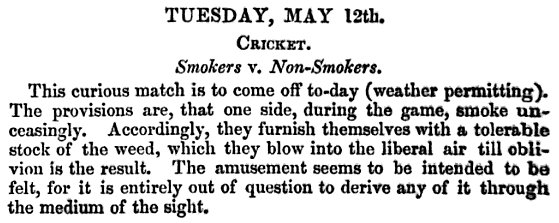

From Henry Colburn’s London “calendar of amusements,” 1840:

From “Eccentric Cricket Matches,” Strand, 1903:

A few winters ago, when a fine stretch of water in Sheffield Park was frozen over, his lordship [the Earl of Sheffield] organized a match on the ice, in which several of his house guests appeared. All the players used skates, the wicket-keeper, as might be imagined, having no little difficulty to keep still, and the bowlers being continually no-balled for running, or rather skating, over the crease. The beauty of ice-cricket lies in the fact that the batsman may score half-a-dozen runs while the fieldsman is endeavouring to regain his feet and pick up the ball, which may be lodged in a bank of snow.

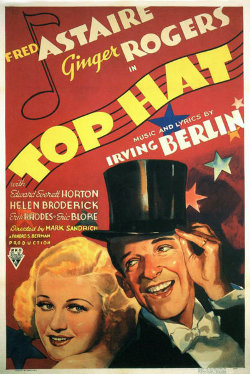

In Top Hat, Ginger Rogers shuns the ardent Fred Astaire because she thinks he’s her best friend’s husband. How she could persist in this belief for any length of time is never explained — the misunderstanding drives the whole story.

This is an “idiot plot,” defined by Roger Ebert as “a plot which is kept in motion solely by virtue of the fact that everybody involved is an idiot.”

The term was coined by science fiction author James Blish, whose colleague Damon Knight added the second-order idiot plot, “in which not merely the principals, but everybody in the whole society has to be a grade-A idiot, or the story couldn’t happen.”

Such contrivances are annoying, but we’ll forgive a lot if we get to watch Fred Astaire dance. “How is it that Ginger has never met her best friend’s husband?” asks critic Alan Vanneman. “Well, Europe is a big place.”