“It is probable that television drama of high caliber and produced by first-rate artists will materially raise the level of dramatic taste of the nation.” — RCA president David Sarnoff, 1939

“Television? The word is half Greek and half Latin. No good can come of it.” — Manchester Guardian editor C.P. Scott, 1928

“Television won’t matter in your lifetime or mine.” — Rex Lambert, The Listener, 1936

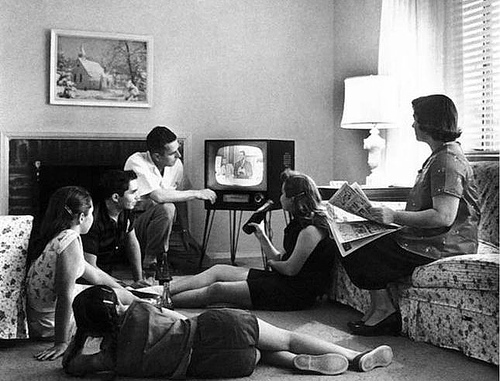

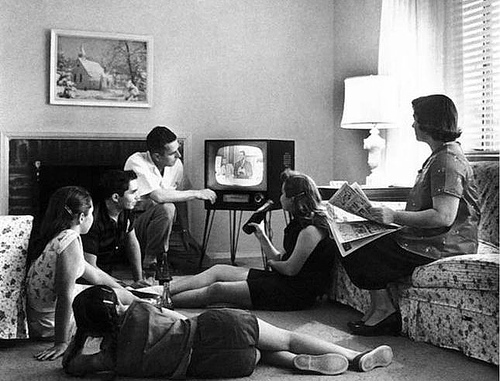

“Television won’t last because people will soon get tired of staring at a plywood box every night.” — movie producer Darryl Zanuck, 1946

“Television won’t last. It’s a flash in the pan.” — BBC school broadcasting director Mary Somerville, 1948

“How can you put out a meaningful drama or documentary that is adult, incisive, probing, when every fifteen minutes the proceedings are interrupted by twelve dancing rabbits with toilet paper?” — Rod Serling, 1974

“I hate television. I hate it as much as peanuts. But I can’t stop eating peanuts.” — Orson Welles, 1956