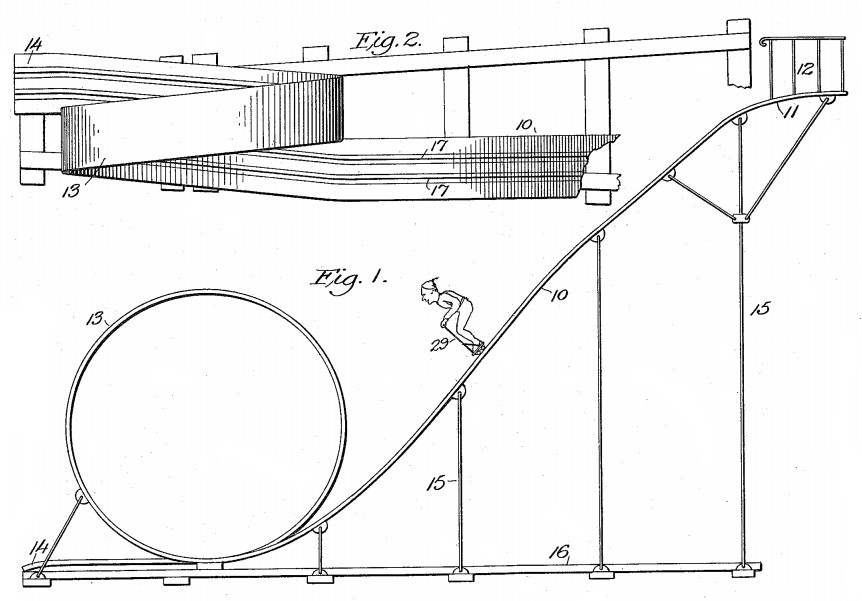

In 1915, Abel Kiansten and John Nelson patented an alarming precursor to the roller coaster in which a victim on roller skates zooms down a ramp and through a loop-the-loop. This is made safe, the inventors assure us, because the skate wheels are secured to the track and the rider is given a little handle to cling to. “Such a support is necessary because the various positions assumed by the performer during his trip would invariably throw the most active athlete from his upright position if some means were not offered him to remain in a standing position.”

It’s not known whether it was ever built. “Many patents were sound and far-reaching, but as many ideas were simply treacherous,” writes Robert Cartmell in The Incredible Scream Machine, his 1987 history of the roller coaster. “It is a blessing some never left the drawing boards or, when built, were closed by lawsuits. Every deviation with tracks was attempted and the eventual safety codes or inspections by insurances companies became beneficial restraints.”