Immanuel Kant held up his stockings using suspenders of his own devising. From his friend Ehregott Wasianski:

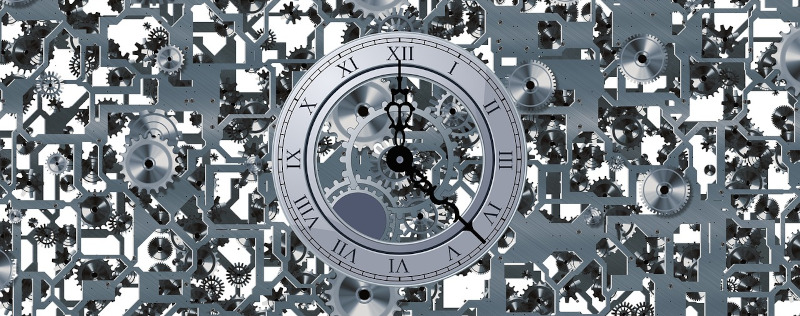

On this occasion, whilst illustrating Kant’s notions of the animal economy, it may be as well to add one other particular, which is, that for fear of obstructing the circulation of the blood, he never would wear garters; yet, as he found it difficult to keep up his stockings without them, he had invented for himself a most elaborate substitute, which I shall describe. In a little pocket, somewhat smaller than a watch-pocket, but occupying pretty nearly the same situation as a watch-pocket on each thigh, there was placed a small box, something like a watch-case, but smaller; into this box was introduced a watch-spring in a wheel, round about which wheel was wound an elastic cord, for regulating the force of which there was a separate contrivance. To the two ends of this cord were attached hooks, which hooks were carried through a small aperture in the pockets, and so passing down the inner and the outer side of the thigh, caught hold of two loops which were fixed on the off side and the near side of each stocking.

“As might be expected, so complex an apparatus was liable, like the Ptolemaic system of the heavens, to occasional derangements; however, by good luck, I was able to apply an easy remedy to these disorders which sometimes threatened to disturb the comfort, and even the serenity, of the great man.”

(Ehregott Andreas Wasianski, Immanuel Kant in seinen letzten Lebensjahren, 1804, via Thomas De Quincey, “The Last Days of Immanuel Kant,” 1827.)