“One of the lessons of history is that nothing is often a good thing to do and always a clever thing to say.” — Will Durant

History

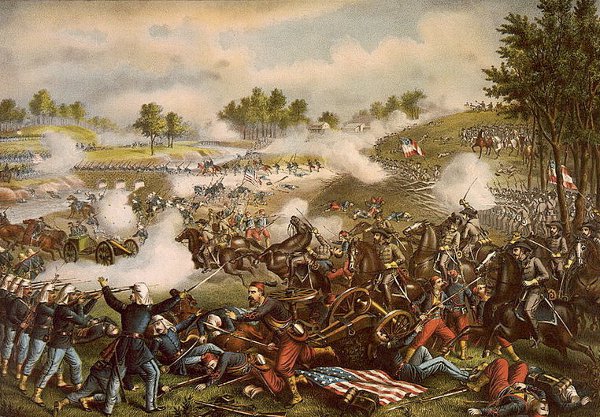

Brothers in Arms

After the First Battle of Manassas, a reporter for the Richmond Dispatch discovered a Confederate soldier tending to a wounded Union infantryman.

“Yes, sir, he is my brother Henry,” he said. “The same mother bore us, the same mother nursed us. We met for the first time in four years. I belong to the Washington Artillery, from New Orleans–he to the First Minnesota Infantry. By the merest chance I learned he was here wounded, and sought him out to nurse and attend to him.”

“Thus they met,” the reporter wrote, “one from the far North, the other from the extreme South–on a bloody field in Virginia, in a miserable stable, far away from their mother, home and friends, both wounded–the infantry man by a musket ball in the right shoulder, the artillery man by the wheel of a caisson over his left hand. Their names are Frederick Hubbard, Washington Artillery, and Henry Hubbard, First Minnesota Infantry.”

Perspective

“The sound of Niagara Falls outdates our most cherished antiquities.” — J.O. Urmson

Cold War

In 1809, the Spanish town of Huéscar declared war on Denmark during the Napoleonic wars over Spain.

The war was forgotten until 1981, when a local historian discovered the declaration.

In 172 years of warfare, not a single person had been killed or injured.

A Shy Pen

Button Gwinnett was a relatively obscure member of the Continental Congress when he signed the Declaration of Independence in August 1776. Nine months later he was killed in a duel.

That makes his signature one of the most valuable in the world, comparable to those of Julius Caesar and William Shakespeare. Only 51 examples exist. This January it was discovered that he’d signed a Wolverhampton marriage register in 1757, five years before departing England for America. That autograph was valued at £500,000.

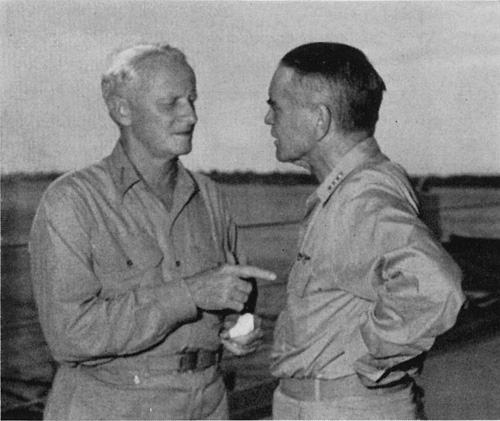

Stormy Seas

On Oct. 25, 1944, during battle in the Philippine Sea, Chester Nimitz sent this message to William Halsey, asking for his location:

TURKEY TROTS TO WATER GG FROM CINCPAC ACTION COM THIRD FLEET INFO COMINCH CTF SEVENTY-SEVEN X WHERE IS RPT WHERE IS TASK FORCE THIRTY FOUR RR THE WORLD WONDERS

The language before GG and after RR is nonsense added to discourage cryptanalysis. Unfortunately, Halsey’s radio officer neglected to remove the trailing phrase, and Halsey read:

Where is, repeat, where is Task Force Thirty Four? The world wonders.

“I was stunned as if I had been struck in the face,” Halsey wrote later. “The paper rattled in my hands, I snatched off my cap, threw it on the deck, and shouted something I am ashamed to remember.” Furious at Nimitz’ “gratuitous insult,” he delayed an hour before rejoining the battle. He learned the truth only weeks later.

(Thanks, Ankit.)

Express

On June 12, 1940, a man strolled onto the platform at Ireland’s Dingle light railway station and asked some workers when the next train would depart for Tralee.

The men stared at him, and one said, “The last train for Tralee left here 14 years ago. I reckon it might be another 14 years before the next train will leave.”

Two hours later the man, Walter Simon, was in a local jail cell. It turned out he was a German spy who had landed that evening by U-boat at Dingle Bay. His spying career was over.

A Living Emblem

During the Civil War, the 8th Wisconsin Volunteer Infantry Regiment had a particularly patriotic mascot — a bald eagle. Named for the commander-in-chief of the Union Army, “Old Abe” accompanied his regiment into battle at the Second Battle of Corinth and the Siege of Vicksburg, screaming at the enemy and spreading his wings. Apparently he was a bit of a ham — in September 1861 the Eau Claire Free Press reported:

When the regiment marched into Camp Randall, the instant the men began to cheer, he spread his wings, and taking one of the small flags attached to his perch in his beak, he remained in that position until borne to the quarters of the late Col. Murphy.

After the war Old Abe resided in the state capitol, where he died in a fire in 1881. Today he lives on in the insignia of the U.S. Army’s 101st Airborne Division.

Underpaid

Early one morning [George III] met a boy in the stables at Windsor and said: ‘Well, boy! What do you do? What do they pay you?’

‘I help in the stable,’ said the boy, ‘but they only give me victuals and clothes.’

‘Be content,’ said George, ‘I have no more.’

— Beckles Willson, George III, 1907

Amused

In 1878 Queen Victoria invited to lunch an elderly naval officer who was hard of hearing. For a time the two discussed the recent sinking of the naval training ship Eurydice. Then, to turn to a lighter subject, the queen inquired after the admiral’s sister.

“Well, ma’am,” he replied, “I am going to have her turned over and take a good look at her bottom and have it well scraped.”

“The effect of his answer was stupendous,” wrote the queen’s grandson, Kaiser Wilhelm II. “My grandmother put down her knife and fork, hid her face in her handkerchief and shook and heaved with laughter till the tears rolled down her face.”