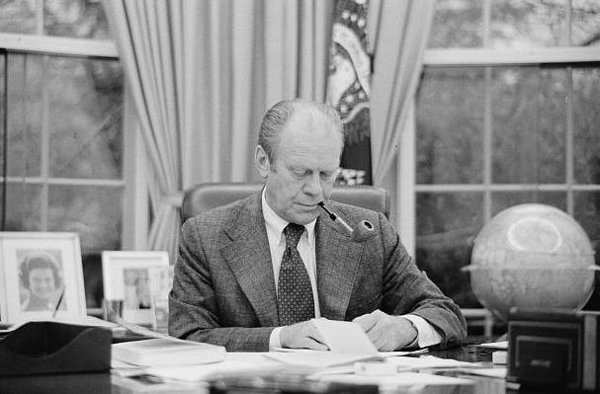

Gerald Ford served as both vice president and president but was elected to neither office.

He was appointed to the vice presidency when Spiro Agnew resigned, and he succeeded Richard Nixon as president.

Gerald Ford served as both vice president and president but was elected to neither office.

He was appointed to the vice presidency when Spiro Agnew resigned, and he succeeded Richard Nixon as president.

Letter from Richard Byrd to his son shortly after establishing Marie Byrd Land, Feb. 22, 1929:

Dear Dickie–

I have named a big new land after mommie because mommie is the sweetest finest and nicest and best person in the world. Take good care of her and be awfully sweet to her while I’m away.

I love you my dear boy.

Daddy

Little America

Antarctica

Supreme Court justice James Clark McReynolds (1862-1946) was known as “the rudest man in Washington.” In 27 years on the court, his behavior made this seem an understatement.

In choosing law clerks, McReynolds refused to accept “Jews, drinkers, blacks, women, smokers, married or engaged individuals.” A blatant antisemite, he refused to speak to Louis Brandeis, the court’s first Jewish justice, and in 1924 refused even to sit next to him for the court’s annual photo. After urging Herbert Hoover not to “afflict the Court with another Jew,” he pointedly read a newspaper during Benjamin Cardozo’s swearing-in ceremony. “For four thousand years,” he told Oliver Wendell Holmes, “the Lord tried to make something out of the Hebrews, then gave it up as impossible and turned them out to prey on mankind in general — like fleas on the dog, for example.”

McReynolds’ intolerance extended to everyone around him. When justice Harlan Fiske Stone remarked on the dullness of one attorney’s argument, McReynolds returned, “The only duller thing I can think of is to hear you read one of your opinions.” He objected to women’s wearing red nail polish and men’s wearing wristwatches, and he declared tobacco smoke “personally objectionable.” He once tried to defend his impartiality by saying he tried to protect “the poorest darkie in the Georgia backwoods as well as the man of wealth in a mansion on Fifth Avenue.”

Chief justice William Howard Taft called McReynolds “selfish to the last degree,” “fuller of prejudice than any man I have ever known,” and “one who delights in making others uncomfortable.” Even historians seem to hate him. In his biographical dictionary of the court, Timothy L. Hall calls McReynolds “the most boorish man ever to hold a seat there,” and Rebecca S. Shoemaker calls him “irascible and a racist.” He died alone at 84 — in Hall’s words, “unwept-for and unloved.”

In the wall of the north portion of the White House is a bell. On a recent afternoon, President Coolidge pressed this bell repeatedly, scampered quickly away. To the north portico rushed a detail of Secret Service men, to whom the bell’s ringing was a summons to come at once. From a distance, the President watched their confusion, heard them ask the Secret Service man on patrol duty why he had rung the bell, heard the patrolman’s denial of any bell-ringing. After the guards had dispersed, the President stole back, again pressed the button, again trotted away, chuckled as the previous scene repeated itself. Pleased, the President several times repeated his little prank. Eventually the Secret Service detail discovered the source of the false alarms, put in another bell in a spot unknown to the President. When this story became public, persons who question the existence of a presidential sense of humor flouted its accuracy. Yet Richard Jervis, head of the Executive Secret Service detail, vouched solemnly for it.

— Time, Jan. 21, 1929

On Jan. 7, 1941, eleven months before the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, ambassador Joseph Clark sent this telegram to the U.S. State Department:

A member of the Embassy was told by my ——- colleague that from many quarters, including a Japanese one, he had heard that a surprise mass attack on Pearl Harbor was planned by the Japanese military forces, in case of ‘trouble’ between Japan and the United States; that the attack would involve the use of all the Japanese military facilities.

Grew added, “My colleague said that he was prompted to pass this on because it had come to him from many sources, although the plan seemed fantastic.”

The U.S. did nothing, but it had already demonstrated its myopia. On Sept. 27, 1940, Douglas MacArthur had said, “Japan will never join the Axis.” Japan joined the Axis the next day.

On Sept. 13, 1862, members of the 27th Indiana Infantry were awaiting orders on a hillside near Frederick, Md., as Robert E. Lee’s Confederate troops approached from the south. One of the men noticed a package on the ground and discovered three cigars wrapped in a piece of paper. The men were rejoicing in their good fortune when a sergeant noticed writing on the paper — it was headed “Headquarters of the Army of Northern Virginia.”

They had discovered Lee’s battle plan. The orders had been issued to Gen. D.H. Hill, but one of his staff officers had apparently dropped them; Hill received a second copy from Stonewall Jackson and had not realized that the first set had been lost.

The plans passed quickly up the line, and that afternoon Union general George C. McClellan was wiring the president, “I have all the plans of the rebels, and will catch them in their own trap.” The battle of Sept. 17, Antietam, was the bloodiest single day of the Civil War. It repelled the rebel army and permitted Lincoln to issue the Emancipation Proclamation from a position of strength.

Lee later told a friend: “I went into Maryland to give battle, and could I have kept Gen. McClellan in ignorance of my position and plans a day or two longer, I would have fought and crushed him.”

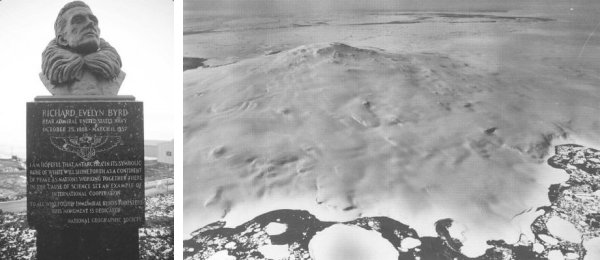

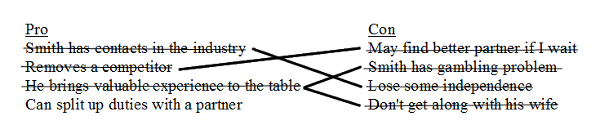

In a 1772 letter to Joseph Priestley, Ben Franklin described a method “for arriving at decisions in doubtful cases.” He would divide a sheet of paper into two columns, labeled Pro and Con, and during the course of three or four days record all the motives for and against the idea. Then he’d assign a weight to each consideration. Where he could find arguments, sometimes in combination, that counterbalanced one another, he would strike them out:

Should I enter into business with Mr. Smith?

(This example is from Paul C. Pasles, Benjamin Franklin’s Numbers, 2008.) This exercise would show him where the balance lay, and if after a day or two of further reflection no additional considerations occurred to him, he would come to a decision.

“Though the weight of reasons cannot be taken with the precision of algebraic quantities, yet, when each is thus considered separately and comparatively, and the whole lies before me, I think I can judge better, and am less liable to make a rash step; and in fact I have found great advantage from this kind of equation, in what may be called moral or prudential algebra.”

Section 3 of the 25th amendment permits a U.S. president to transfer his authority voluntarily to his vice president when he is “unable to discharge the powers and duties of his office.”

To date it’s been invoked only three times — in 1985 George H.W. Bush served as acting president while surgeons removed a cancerous polyp from Ronald Reagan’s colon, and in 2002 and 2007 Dick Cheney served while George W. Bush underwent colonoscopies.

So, to date, Section 3 has been invoked only for colon issues. Write your own joke.

The Olympics used to include art competitions. Between 1912 and 1952, medals were awarded in architecture, literature, music, painting, and sculpture; even the Soviets contributed art to the 1924 Paris games, though they disdained the sporting events as “bourgeois.” An exhibition at the 1932 games drew 384,000 visitors to the Los Angeles Museum of History, Science and Art.

All works had to be inspired by sports; those ranked highest received gold, silver, and bronze medals. The categories included epic literature, chamber music, watercolors, and statuary; the 1928 games even included a competition in town planning.

In two cases champion athletes also won art competitions. Hungarian swimmer Alfréd Hajós, left, who had won two gold medals in Athens in 1896, took home a silver medal for designing a stadium in 1924. And American Walter Winans won gold both as a marksman in 1908 and as a sculptor in 1912.

In 1954 the art competitions were dropped because most of the participants were professionals, which was held to conflict with the ideals of the games. But the Olympic charter still requires hosts to include a cultural program “to promote harmonious relations, mutual understanding and friendship among the participants and others attending the Olympic Games.”

In September 1918, during the closing months of World War I, Everybody’s Magazine published a prophetic article by Eugene P. Lyle. “The War of 1938” (subtitled “A Terrible Warning Against a Premature Peace”) depicted a future in which the war-weary Allies accepted a peace offer in 1918 rather than pressing the conflict to a decisive victory.

In Lyle’s vision, Germany disarms and pays reparations but immediately begins planning a Prussian “night of consummation.” Her freed merchant fleet begins gathering material with the slogan “Germany must not be merely efficient, but self-sufficient,” and in 1938, at the end of a 20-year debt moratorium, she unleashes a blitzkrieg that sweeps Europe. England is stormed from the air, and her overseas dominions and the United States await a final onslaught in Egypt and India. The article ends:

In all the wretched lexicon of regret there is no word more futile than the ghastly word ‘if.’ It avails nothing, ever, and yet tonight the word is branded deep on the aching heart of humanity — ‘IF we had only seen the thing through in 1918!’

Readers called Lyle an “irresponsible alarmist,” a “sensation monger,” and a muckraker, but many of his fears would be realized. A few years after the armistice Pershing remarked to a friend, “They don’t know they were beaten in Berlin, and it will all have to be done all over again.”