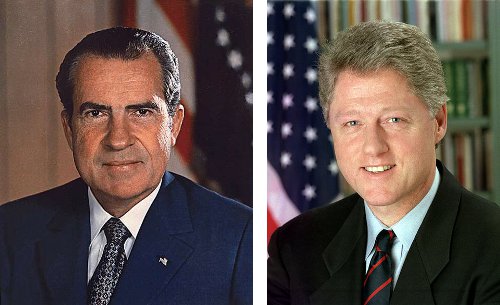

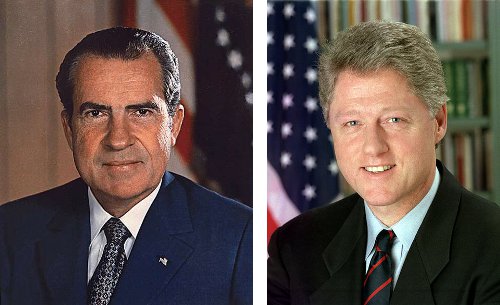

RICHARD MILHOUS NIXON and WILLIAM JEFFERSON CLINTON are the only U.S. presidents whose names contain the letters C-R-I-M-I-N-A-L.

RICHARD MILHOUS NIXON and WILLIAM JEFFERSON CLINTON are the only U.S. presidents whose names contain the letters C-R-I-M-I-N-A-L.

Harry B. Partridge points out that most presidents whose names have contained a penultimate L — Ronald Reagan, Abraham Lincoln, James Garfield, Franklin Roosevelt, John Fitzgerald Kennedy — have died in office or survived an assassination attempt. He speculates that Gerald Ford survived because he was born Leslie Lynch King Jr., and that Theodore Roosevelt was divinely spared because THEO means God. (James Polk died three months after leaving office.)

Partridge also notes that a name with patronymic prefix (Mc, Fitz, etc.) is invariably fatal. To date there have been only two: William McKinley and John Fitzgerald Kennedy.

See Tecumseh’s Curse.

While a law student at Duke University, Richard Nixon broke in to the dean’s office with two friends to see their forthcoming grades.

“They replaced everything, took nothing, damaged nothing, and committed no indiscretions,” writes Conrad Black in his 2008 biography of the president. “Yet some Nixonophobes have suggested that this was a foretaste of felonious behavior, and of a propensity for office break-ins.”

In 1857 archaeologists unsealed an ancient house on the Palatine Hill in Rome. Inside, carved into the plaster of one of the walls, they found this inscription.

It appears to show a donkey-headed figure attached to a cross. A young man raises his hand to it, perhaps in worship. Below this is written in crude Greek, “Alexamenos worships [his] God.”

It’s believed to be one of the first representations of the crucifixion of Jesus.

As the Mayflower was crossing the Atlantic in 1620, passenger John Howland was swept overboard during a storm. He managed to sieze a trailing halyard and was pulled back to safety. His descendants in the New World have included:

If Howland had lost his life in that storm, none of these people would have existed.

“We request that every hen lay 130 to 140 eggs a year. The increase cannot be achieved by the bastard hens (non-Aryan) which now populate German farmyards. Slaughter these undesirables and replace them.” — Nazi Party news agency, April 3, 1937

“Quite a number of people … describe the German classical author, Shakespeare, as belonging to English literature, because — quite accidentally born at Stratford-on-Avon — he was forced by the authorities of that country to write in English.” — New York National Socialist organ Deutscher Weckruf und Beobachter, quoted in The American Mercury, July 1940

“The rabbit, it is certain, is no German animal, if only for its painful timidity. It is an immigrant who enjoys a guest’s privilege. As for the lion, one sees in him indisputably German fundamental characteristics. Thus one could call him a German abroad.” — Gen. Erich Ludendorff in Am Quell Deutscher Kraft

“Proper breathing is a means of acquiring heroic national mentality. The art of breathing was formerly characteristic of true Aryanism and known to all Aryan leaders.” — Weltpolitische Rundschau, Berlin

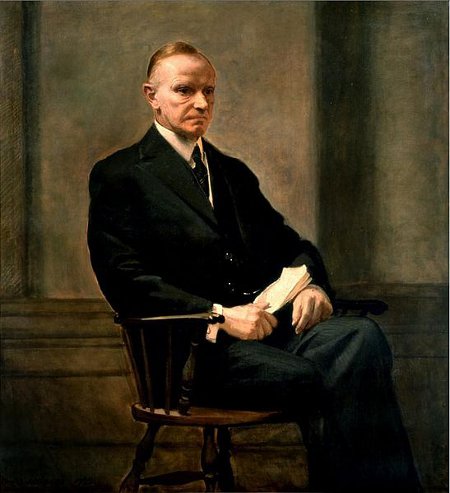

Ambassador Richard Washburn Child once dined with Calvin Coolidge at the White House.

After dinner, the president said he had something to show him. He led Child to one of the smaller rooms in the mansion, opened the door, and turned on the light.

“On the opposite wall hung a portrait of himself,” Child later recalled. “I thought it so very bad I could think of nothing to say.”

For a long moment the two men stood on the threshold. Then Coolidge snapped off the light and closed the door.

“So do I,” he said.

An Austrian army, awfully arrayed,

Boldly by battery beseiged Belgrade;

Cossack commanders cannonading come,

Dealing destruction’s devastating doom;

Every endeavour engineers essay

For fame, for fortune, forming furious fray;

Gaunt gunners grapple, giving gashes good;

Heaves high his head heroic hardihood;

Ibraham, Islam, Ismail, imps in ill,

Jostle John, Jarovlitz, Joe, Jack, Jill,

Kick kindling Kutosoff, kings’ kinsmen kill;

Labor low levels loftiest, longest lines;

Men marched ‘mid moles, ‘mid mounds, ‘mid murd’rous mines.

Now nightfall’s near, now needful nature nods,

Opposed, opposing, overcoming odds.

Poor peasants, partly purchased, partly pressed,

Quite quaking, Quarter! quarter! quickly quest.

Reason returns, recalls redundant rage,

Saves sinking soldiers, softens seigniors sage.

Truce, Turkey, truce! Truce, treach’rous Tartar train!

Unwise, unjust, unmerciful Ukraine!

Vanish, vile vengeance! Vanish, victory vain!

Wisdom wails war — wails warring words. What were

Xerxes, Xantippe, Ximenes, Xavier?

Yet Yassey’s youth, ye yield your youthful yest,

Zealously, zanies, zealously, zeal’s zest.

— William T. Dobson, Literary Frivolities, Fancies, Follies and Frolics, 1880

Excerpts from the Harvard Economic Society’s Weekly Letter, 1929-1930:

In 1931, strapped by the depression, the Letter ceased publication.

From Clark Kinnaird’s Encyclopedia of Puzzles and Pastimes, 1946:

Though a great American, Wendell Willkie nevertheless lacked one of the four necessary requirements for becoming President of the United States. One must be at least 35, a native-born American, and a resident of the U.S.A. for at least 14 years. Name the fourth requirement which Willkie also lacked?