- Georgia, Massachusetts, and Connecticut didn’t ratify the Bill of Rights until 1939.

- Wilt Chamberlain never fouled out of a game.

- 3864 = 3 × (-8 + 64)

- What’s the opposite of “not in”?

- Alaska has a longer coastline than all other U.S. states combined.

- “To do nothing is also a good remedy.” — Hippocrates

History

Inksmanship

In 1863, the register of the U.S. Treasury, L.E. Chittenden, had to sign 12,500 bonds in a single weekend to stop the delivery of two British-built warships to the Confederacy. He started at noon on Friday and managed 3,700 signatures in the first seven hours, but by Saturday morning he was desperate:

[E]very muscle on the right side connected with the movement of the hand and arm became inflamed, and the pain was almost beyond endurance. … In the slight pauses which were made, rubbing, the application of hot water, and other remedies were resorted to, in order to alleviate the pain and reduce the inflammation. They were comparatively ineffectual, and the hours dragged on without bringing much relief.

He finished, exhausted, at noon on Sunday, completing a mountain of bonds more than 6 feet high. These were rushed to a waiting steamer — and only then did word come that the English warships had been sold to a different buyer. The bonds, in the end, were not needed.

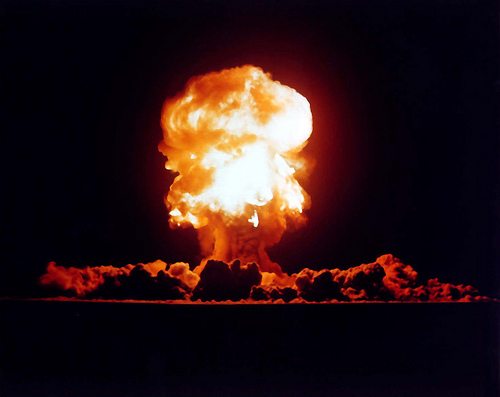

Fire Fight

In October 1962, during the Cuban Missile Crisis, a group of American destroyers trapped a Soviet submarine near Cuba. When the ships began dropping depth charges, the sub’s captain prepared to launch a nuclear-tipped torpedo, believing that a war between the superpowers might already be under way.

But the launch was permitted only if three officers agreed to it, and second-in-command Vasili Arkhipov held out against his superior. An argument ensued, but eventually he persuaded the captain to surface instead and seek orders from Moscow.

“The lesson from this,” remarked NSA director Thomas Blanton in 2002, “is that a guy called Vasili Arkhipov saved the world.”

See Close Call.

Domestic Harmony

The Musical World of London, Nov. 28, 1874, reports a surprising project — apparently a Massachusetts composer set the entire American constitution to music:

The authors of the Constitution of the Union thought more of reason than of rhyme, and their prose is not too well adapted to harmony, but the patriotic inspiration of Mr. Greeler, the Boston composer, overcomes every difficulty. He has made his score a genuine musical epopœia, and had it performed before a numerous public. The performance did not last less than six hours. The preamble of the Constitution forms a broad and majestic recitative, well sustained by altos and double basses. The first clause is written for a tenor; the other choruses are given to the bass, soprano, and baritone. The music of the clause treating of state’s rights is written in a minor key for bass and tenor. At the end of every clause, the recitative of the preamble is re-introduced and then repeated by the chorus. The constitutional amendments are treated as fugues and serve to introduce a formidable finale, in which the big drum and the gong play an important part. The general instrumentation is very scholarly, and the harmony surprising.

The music has been lost, but it would be out of date now anyway — we’ve added 12 amendments since then.

Comment

Dorothy Parker named her Boston terrier Woodrow Wilson “because he was full of shit.”

The Other Side

An episode from the German trenches, August 1915, from artilleryman Herbert Sulzbach’s 1935 memoir With the German Guns:

One of the next starlit summer nights, a decent Landwehr chap came up suddenly and said to 2/Lt Reinhardt, ‘Sir, it’s that Frenchie over there singing again so wonderful.’ We stepped out of the dug-out into the trench, and quite incredibly, there was a marvellous tenor voice ringing out through the night with an aria from Rigoletto. The whole company were standing in the trench listening to the ‘enemy,’ and when he had finished, applauding so loud that the good Frenchman must certainly have heard it and is sure to have been moved by it in some way or other as much as we were by his wonderful singing.

“Musical compositions, it should be remembered, do not inhabit certain countries, certain museums, like paintings and statues,” wrote Henri Rabaud. “The Mozart Quintet is not shut up in Salzburg: I have it in my pocket.”

Unquote

“This is the biggest fool thing we have ever done. The bomb will never go off, and I speak as an expert in explosives.” — Admiral William D. Leahy to Harry Truman, 1945

Nearer My God

Buzz Aldrin celebrated communion on the moon. From his 2009 book Magnificent Desolation:

So, during those first hours on the moon, before the planned eating and rest periods, I reached into my personal preference kit and pulled out the communion elements along with a three-by-five card on which I had written the words of Jesus: ‘I am the vine, you are the branches. Whoever remains in me, and I in him, will bear much fruit; for you can do nothing without me.’ I poured a thimbleful of wine from a sealed plastic container into a small chalice, and waited for the wine to settle down as it swirled in the one-sixth Earth gravity of the moon. My comments to the world were inclusive: ‘I would like to request a few moments of silence … and to invite each person listening in, wherever and whomever they may be, to pause for a moment and contemplate the events of the past few hours, and to give thanks in his or her own way.’ I silently read the Bible passage as I partook of the wafer and the wine, and offered a private prayer for the task at hand and the opportunity I had been given.

“Perhaps, if I had it to do over again, I would not choose to celebrate communion,” he wrote. “Although it was a deeply meaningful experience for me, it was a Christian sacrament, and we had come to the moon in the name of all mankind — be they Christians, Jews, Muslims, animists, agnostics, or atheists. But at the time I could think of no better way to acknowledge the enormity of the Apollo 11 experience that by giving thanks to God.”

Caught!

When Eisenhower took office in 1953, a group of conservative Republicans claimed that the outgoing Democrats had been stealing gold deposits from Fort Knox.

Bowing to pressure from the Daughters of the American Revolution, Eisenhower had the gold counted. Sure enough, it came up ten bucks short: The depository contained only $30,442,415,581.70.

Truman’s treasurer, Georgia Clark, rolled her eyes and sent a check to cover the shortfall.

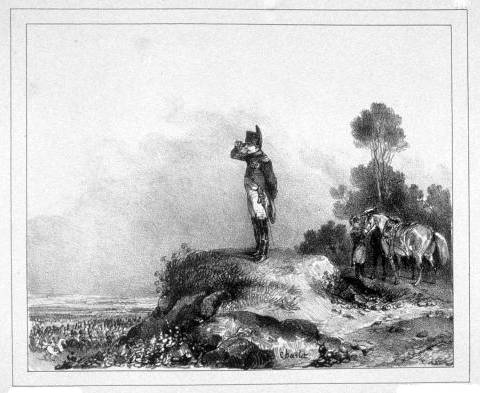

“Bonaparte and the Echo”

Bonaparte: Alone I am in this sequestered spot, not overheard.

Echo: Heard.

Bonaparte: ‘Sdeath! Who answers me? What being is there nigh?

Echo: I.

Bonaparte: Now I guess! To report my accents Echo has made her task.

Echo: Ask.

Bonaparte: Knowest thou whether London will henceforth continue to resist?

Echo: Resist.

Bonaparte: Whether Vienna and other courts will oppose me always?

Echo: Always.

Bonaparte: O, Heaven! what must I expect after so many reverses?

Echo: Reverses.

Bonaparte: What! should I, like a coward vile, to compound be reduced?

Echo: Reduced.

Bonaparte: After so many bright exploits be forced to restitution?

Echo: Restitution.

Bonaparte: Restitution of what I’ve got by true heroic feats and martial address?

Echo: Yes.

Bonaparte: What will be the fate of so much toil and trouble?

Echo: Trouble.

Bonaparte: What will become of my people, already too unhappy?

Echo: Happy.

Bonaparte: What should I then be that I think myself immortal?

Echo: Mortal.

Bonaparte: The whole world is filled with the glory of my name, you know.

Echo: No.

Bonaparte: Formerly its fame struck this vast globe with terror.

Echo: Error.

Bonaparte: Sad Echo, begone! I grow infuriate! I die!

Echo: Die!

It’s said that the Nuremberg bookseller who penned this clever bit of sedition was court-martialed and shot in 1807. Napoleon later said, “I believe he met with a fair trial.”