An American reporter discovered this inscription on the wall of a Verdun fortress in 1945:

Austin White–Chicago, Ill.–1918

Austin White–Chicago, Ill.–1945

This is the last time I want to write my name here.

An American reporter discovered this inscription on the wall of a Verdun fortress in 1945:

Austin White–Chicago, Ill.–1918

Austin White–Chicago, Ill.–1945

This is the last time I want to write my name here.

Under the terms of an 1845 treaty, Texas has the right to divide itself at any time into five new states.

That was part of the deal when the Lone Star State was first annexed to the Union, and, according to University of Minnesota law professor Michael Stokes Paulsen, it’s still valid and constitutional.

Such a move would create eight new senators and four new governors — and it would add eight votes to the Electoral College.

Picasso’s Guernica depicts the suffering wrought by a German bombing in 1937 during the Spanish Civil War.

Three years later, when the artist was living in Nazi-occupied Paris, a Gestapo officer saw a photo of the painting in his apartment. “Did you do that?” he asked.

“No,” Picasso said. “You did.”

Stigler’s Law of Eponymy states that “no scientific discovery is named after its original discoverer.” Examples:

University of Chicago statistics professor Stephen Stigler advanced the idea in 1980.

Delightfully, he attributes it to Robert Merton.

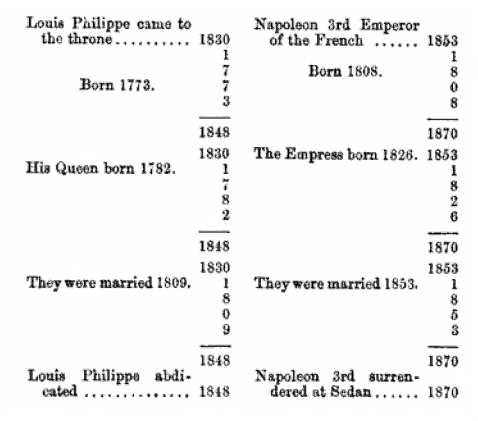

Curious coincidences in the lives of Louis Philippe and Napoleon III, from a French daily paper of 1869 — the central events in their lives seem to foretell their downfall:

See The Stars Align.

In 1808, a French gentleman bought 2,700 acres in Georgetown, N.Y., and erected a chateau on the highest hill. Evidently he was massively wealthy, landscaping the grounds extensively and ordering a hamlet built on the estate, after the fashion of the great French nobles. And he seemed fearful for his safety, securing the house against gunfire and clearing the woods around it.

He roved the estate on horseback, attended by armed servants, and was described as erect, agile, and commanding. When asked to muster for the local militia he responded with outrage, saying he had led a division and participated in making three treaties, but he gave no other clues to his identity. He followed closely the progress of the War of 1812 and of Napoleon, whose ascendancy he evidently feared; when the Corsican met disaster in Russia he returned abruptly to France.

Who was this man? He gave his name as Louis Anathe Muller, but he guarded his true identity closely. Was he a French duke? A son of Charles X? The future king himself? With only circumstantial evidence, there’s no way to be certain. After Waterloo he sold the estate for a fraction of its value, and he never returned to New York.

“Nobody now fears that a Japanese fleet could deal an unexpected blow on our Pacific possessions. … Radio makes surprise impossible.”

— Josephus Daniels, former U.S. secretary of the navy, Oct. 16, 1922

In Collectanea de Rebus Hibernicus, his 1791 disquisition on Irish antiquities, Charles Vallancey describes a group of sepulchral stones on the Hill of Tara, one of which is inscribed BELI DIVOSE, “To Belus, God of Fire.”

Vallancey goes into some detail interpreting this as an altar to Baal. It turned out later that a wanderer had lain upon the stone and idly carved his name and the date upside down: E. CONID 1731.

Vallancey’s reaction is not recorded.

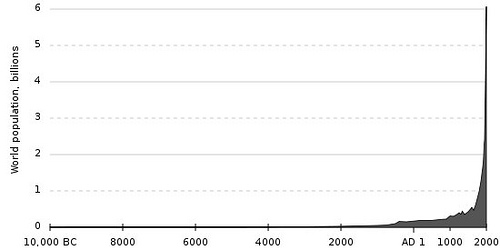

The world population has doubled between:

It’s expected to reach 9 billion by 2040.

On April 12th, a three days’ battle opened at Shaiba with an attack by a motley army of 22,000 Turks, Kurds, and Arabs commanded by German officers. During the thick of the fighting, and when success was well within their grasp, the Turkish forces ceased firing and fled in wild panic from field.

A Turkish prisoner subsequently explained the cause of the Turkish withdrawal. It appears that a pack train, approaching the British line from the rear, had been so distorted by a mirage that it appeared to the Turks as a great body of reinforcements. Believing themselves to be fighting against enormous odds, they had yielded up a victory almost won.

– William C. King, King’s Complete History of the World War, 1922