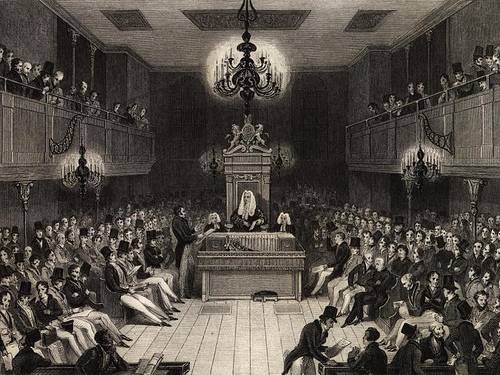

Technically, it’s illegal to resign from the British House of Commons. Since 1623 the rules have stated that a member of Parliament cannot renounce the trust of his constituents.

So members use a loophole: An MP who accepts an office of profit under the Crown must leave his post to avoid a conflict of interest. So today when an MP wishes to resign, the chancellor of the exchequer appoints him crown steward of the Chiltern Hundreds or of the Manor of Northstead, and he can legally resign.

But even this workaround gets awkward. Because there are only two available offices, sometimes MPs must wait in line. When 15 Ulster unionists resigned en masse on Dec. 17, 1985, they had to be appointed one after another in quick succession through the day. What will future historians make of this?