At 120 feet, the Wright Brothers’ first flight would fit inside a modern Boeing 747.

In the economy section.

At 120 feet, the Wright Brothers’ first flight would fit inside a modern Boeing 747.

In the economy section.

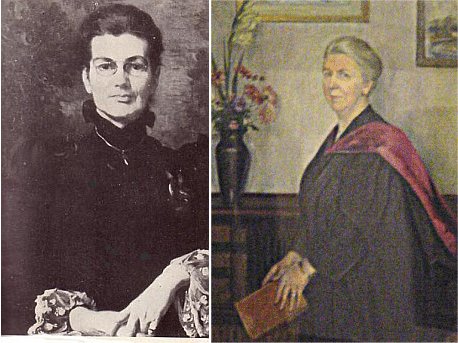

On Aug. 10, 1901, Charlotte Anne Moberly and Eleanor Jourdain were visiting Versailles when they were overcome by a feeling of oppression. They became lost and encountered a number of unusual people, including a man with a scarred face, a fair-haired lady sketching on the grounds, and a group of “very dignified officials, dressed in long greyish green coats with small three-cornered hats.”

Months later, in researching the history of the Trianon, they came to believe that they had somehow slipped back in time on that day to the 1770s and had there met the Comte de Vaudreuil and Marie Antoinette. Their account, published in 1911 as An Adventure, created a sensation but was ultimately dismissed. Moberly and Jourdain were respected academics, but their book simply offered no compelling evidence for their claim.

Nor have any French historians found a record of two bewildered women appearing at Versailles in the 18th century.

Two weeks before Lindbergh’s famous crossing, two French war heroes set out in a biplane to attempt the first nonstop transatlantic flight from Paris to New York.

They took off early on May 8, 1927, and were sighted at the French coast and later off Ireland. But no further sightings were made, and after 42 hours the White Bird was listed as lost.

Possibly she was simply the victim of an Atlantic squall. An extensive search between New York and Newfoundland discovered nothing. But witnesses there claimed to have heard the aircraft, and scattered sightings were reported on a line south from Nova Scotia into coastal Maine. Later, struts and engine metal were found that are not manufactured in North America.

But none of this is conclusive, and no definitive trace of the wooden craft has yet been found — in particular, its engine. In 1984 the French government declared officially that the pair might have reached Newfoundland. But whether they did remains unknown.

When, at the General Peace of 1814, Prussia absorbed a portion of Saxony, the king issued a new coinage of rix dollars, with their German name, EIN REICHSTAHLER, impressed on them. The Saxons, by dividing the word, EIN REICH STAHL ER, made a sentence of which the meaning is, ‘He stole a kingdom!’

— William T. Dobson, Poetical Ingenuities and Eccentricities, 1882

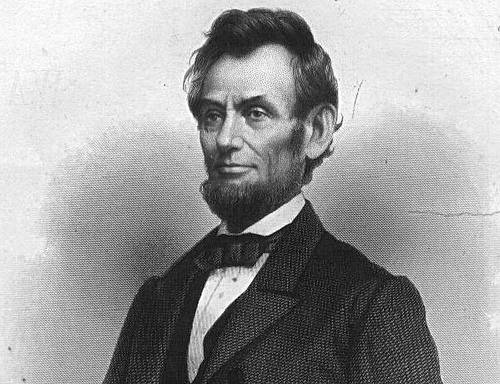

A queer dream or illusion had haunted Lincoln at times through the winter [of 1860]. On the evening of his election he had thrown himself on one of the haircloth sofas at home, just after the first telegrams of November 6 had told him he was elected President, and looking into a bureau mirror across the room he saw himself full length, but with two faces. … A few days later he tried it once more and the illusion of the two faces again registered to his eyes. But that was the last; the ghost since then wouldn’t come back, he told his wife, who said it was a sign he would be elected to a second term, and the death pallor of one face meant he wouldn’t live through his second term.

— Carl Sandburg, Abraham Lincoln: The Prairie Years, 1926

When Dr. Franklin went to France on his revolutionary mission, his eminence as a philosopher, his venerable appearance, and the cause on which he was sent, rendered him extremely popular — for all ranks and conditions of men there entered warmly into the American interest. He was, therefore, feasted and invited to all the court parties. At these he sometimes met the old Duchess of Bourbon, who being a chess-player of about his force, they were very generally played together. Happening once to put her king into prise, the Doctor took it. ‘Ah,’ says she, ‘we do not take kings so.’ ‘We do in America,’ said the Doctor.

— Sarah Randolph, The Domestic Life of Thomas Jefferson, 1871

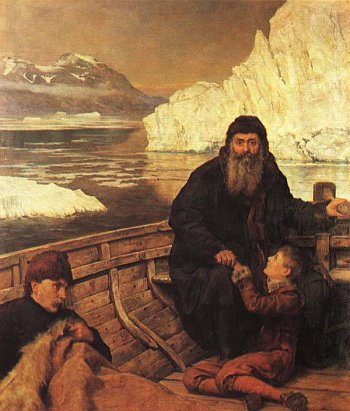

No one knows how Henry Hudson died.

A mutinous crew set the explorer adrift in Hudson Bay in 1611, and he was never seen again.

During the siege of Paris, the city’s starving populace ate its horses, dogs, and cats, and eventually even turned to rats and zoo animals. In Paris in Its Splendor (1900), Eustace Reynolds-Ball gives the menu of a popular restaurant in the Latin Quarter at the beginning of January 1871, “which gives a good idea of the gastronomic straits to which the light-hearted Parisians were reduced”:

See also Balloon Mail.

In 1626 Peter Minuit, first governor of New Netherland, purchased Manhattan Island from the Indians for about $24. … Assume for simplicity a uniform rate of 7% from 1626 to the present, and suppose that the Indians had put their $24 at interest at that rate … and had added the interest to the principal yearly. What would be the amount now, after 280 years? 24 × (1.07)280 = more than 4,042,000,000. [The current value of Manhattan is] a little more than $4,898,400,000. … The Indians could have bought back most of the property now, with improvements; from which one might point the moral of saving money and putting it at interest!

— W.F. White, A Scrap-Book of Elementary Mathematics, 1908

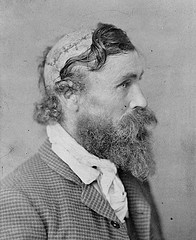

Some scalping victims survived. At left is Robert McGee, who was scalped as a teenager by Sioux chief Little Turtle in 1864.

Texas settler Josiah P. Wilbarger was scalped by Comanches in August 1833. He later recalled that “while no pain was perceptible, the removing of his scalp sounded like the ominous roar and peal of distant thunder,” recounts James De Shields in Border Wars of Texas.

“Rapidly Wilbarger recovered his usual health, and lived for eleven years, prospering, and accumulating a handsome estate. But his skull, bereft of the inner membrane and so long exposed to the sun, never entirely covered over, necessitating artificial covering, and eventually caused his death, hastened, as his physician, Dr. Anderson, thought, by accidentally striking his head against the upper portion of a low door frame of his gin house, causing the bone to exfoliate, exposing the brain and producing delirium.” He died in 1845.