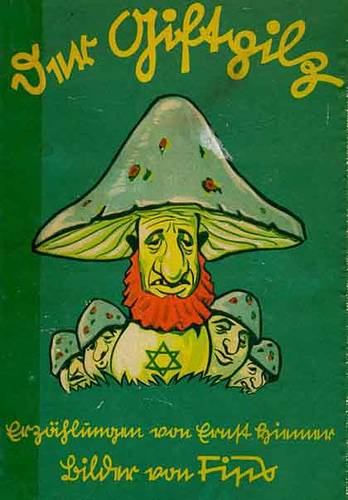

Yes, it’s a Jewish toadstool.

In 1938, fanatical Nazi Julius Streicher published a children’s book called Der Giftpilz (The Poisoned Mushroom), which compared perfidious Jews to poisonous fungus.

“Our boys and girls must learn to know the Jew,” a mother warns her children. “They must learn that the Jew is the most dangerous poison mushroom in existence. Just as poisonous mushrooms spring up everywhere, so the Jew is found in every country in the world. Just as poisonous mushrooms lead to the most dreadful calamity, so the Jew is the cause of misery and distress, illness and death.”

Disturbingly, Streicher had worked as an elementary school teacher before joining the German army in 1914. He published propaganda for Hitler, and after Nuremberg he was the only sentenced Nazi to declare “Heil Hitler” before being hanged. At least he was consistent.