Some years ago, when she was very young, Elizabeth was asked what she would like to be when she grew up. Without a moment’s hesitation she answered, ‘I should like to be a horse.’

— William W. White, “Princess Elizabeth,” Life, Aug. 20, 1945

Some years ago, when she was very young, Elizabeth was asked what she would like to be when she grew up. Without a moment’s hesitation she answered, ‘I should like to be a horse.’

— William W. White, “Princess Elizabeth,” Life, Aug. 20, 1945

As the U.S. tariff act of June 6, 1872, was being drafted, planners intended to exempt “Fruit plants, tropical and semi-tropical for the purpose of propagation or cultivation.”

Unfortunately, as the language was being copied, a comma was inadvertently moved one word to the left, producing the phrase “Fruit, plants tropical and semi-tropical for the purpose of propagation or cultivation.”

Importers pounced, claiming that the new phrase exempted all tropical and semi-tropical fruit, not just the plants on which it grew.

The Treasury eventually had to agree that this was indeed what the language now said, opening a loophole for fruit importers that deprived the U.S. government of an estimated $1 million in revenue. Subsequent tariffs restored the comma to its intended position.

George Washington’s teenage journal contains this love acrostic:

From your bright sparkling Eyes, I was undone;

Rays, you have, more transparent than the sun,

Amidst its glory in the rising Day,

None can you equal in your bright arrays;

Constant in your calm and unspotted Mind;

Equal to all, but will to none Prove kind,

So knowing, seldom one so Young, you’l Find.

Ah! woe’s me, that I should Love and conceal,

Long have I wish’d, but never dare reveal,

Even though severely Loves Pains I feel;

Xerxes that great, was’t free from Cupids Dart,

And all the greatest Heroes, felt the smart.

Reading the first letter of each line spells FRANCES ALEXA. Who was this? Possibly the subject’s full name was Frances Alexander and Washington hadn’t finished the poem.

Twenty-two acknowledged concubines, and a library of sixty-two thousand volumes, attested the variety of his inclinations; and from the productions which he left behind him, it appears that the former as well as the latter were designed for use rather than for ostentation.

— Edward Gibbon, on the Roman emperor Gordian II

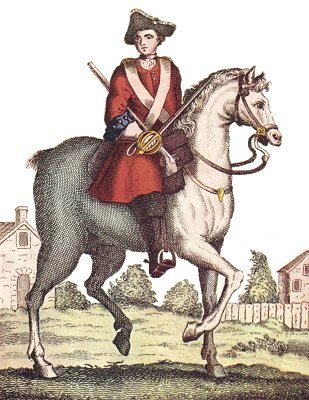

In 1691, on learning that her missing husband was serving in the British Army in Holland, Irish publican Christian Cavanagh disguised herself as a man to go after him. Wounded and captured at the Battle of Landen, she was exchanged back into service, killed another soldier in a duel, was discharged, re-enlisted as a dragoon, and fought with the Scots Greys in the War of the Spanish Succession, all while persuading her fellow soldiers that she was a man.

Author Marian Broderick writes, “[S]he ate with them, drank with them, slept with them, played cards with them, even urinated alongside them by using what she describes as a ‘silver tube with leather straps’. No one was ever the wiser.”

After the Battle of Blenheim she discovered her husband with another woman and decided to remain a dragoon rather than rejoin him. A surgeon finally discovered her secret in 1706, when her skull was fractured in the Battle of Ramillies. Discharged, she served the unit as a sutler until 1712. Hearing the remarkable tale, Queen Anne granted her a bounty of £50 and a shilling a day for the rest of her life.

The next important ceremony in which I was officially concerned was the Coronation of King Edward [VII, in 1902]. … Before the Coronation I had a remarkable dream. The State coach had to pass through the Arch at the Horse Guards on the way to Westminster Abbey. I dreamed that it stuck in the Arch, and that some of the Life Guards on duty were compelled to hew off the Crown upon the coach, before it could be freed. When I told the Crown Equerry, Colonel Ewart, he laughed and said, ‘What do dreams matter?’ ‘At all events’, I replied, ‘let us have the coach and the arch measured.’ So this was done; and, to my astonishment, we found that the arch was nearly two feet too low to allow the coach to pass through. I returned to Colonel Ewart in triumph, and said, ‘What do you think of dreams now?’ ‘I think it’s damned fortunate you had one,’ he replied. It appears that the State Coach had not been driven through the arch for some time, and that the level of the road had since been raised during repairs. So I am not sorry that my dinner disagreed with me that night; and I only wish all nightmares were as useful.

That’s from Men Women and Things, the 1937 memoir of William Cavendish-Bentinck, 6th Duke of Portland. An even more striking moment occurred 11 years later, when Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria visited England and the Portlands received him at Welbeck Abbey. During the weeklong visit, Portland and the archduke were shooting on the estate when “one of the loaders fell down. This caused both barrels of a gun he was carrying to be discharged, the shot passing within a few feet of the Archduke and myself. I have often wondered whether the Great War might not have been averted, or at least postponed, had the Archduke met his death then, and not at Sarajevo in the following year.”

On Aug. 6, 1945, 24-year-old Jacob Beser was the radar specialist aboard the Enola Gay when it dropped the atomic bomb on Hiroshima.

Three days later, Beser was aboard the B-29 Bockscar when it dropped the bomb on Nagasaki.

He is the only person who served as a strike crew member on both missions.

Below him, Japanese marine engineer Tsutomu Yamaguchi endured the first bombing during a business trip to Hiroshima, then returned home to Nagasaki in time to receive the second.

He is the only person acknowledged by the Japanese government to have survived both bombings.

Two affecting episodes from the Johnstown Flood of 1889, in which a dam failure sent almost 15 million cubic meters of water down the Little Conemaugh river of western Pennsylvania:

Six-year-old Gertrude Quinn Slattery was riding a wet, muddy mattress through the floodwaters when a man leapt from a passing roof and struggled across to her. “I put both arms around his neck and held on to him like grim death.” They approached a white building from which two men were extending poles from an upper window to rescue victims floating by.

I was too far out for the poles, so the men called:

‘Throw that baby over here to us.’

My hero said: ‘Do you think you can catch her?’

They said: ‘We can try.’

So Maxwell McAchren threw me across the water (some say twenty feet, others fifteen. I could never find out, so I leave it to your imagination. It was considered a great feat in the town, I know.)

Anna Fenn Maxwell’s husband was washed away from a neighbor’s house moments before the flood struck the Fenn home.

I had the baby in my arms and the other children climbed on the lounge and table. The water rose and floated us until our heads nearly touched the ceiling. I held the baby as long as I could and then had to let her drop into the water. George had grasped the curtain pole and was holding on. Something crashed against the house, broke a hole in the wall land a lot of bricks struck my boy on the head. The blood gushed from his face, he loosed his hold and sank out of sight. Oh it was too terrible!

My brave Bismark went next. Anna, her father’s pet, was near enough to kiss me before she slipped under the water. It was dark and the house was tossing every way. The air was stifling, and I could not tell just the moment the rest of the children had to give up and drown. My oldest boy, John Fulton, kept his head above the water as long as he was able. At last he said: ‘Mother, you always said Jesus would help. Will he help us now?’ What could I do but answer that Jesus would be with him, whether in this world or the brighter one beyond the skies? He thought we might get out into the open air. We could not force a way through the wall of the ceiling, and the poor boy ceased to struggle. What I suffered, with the bodies of my seven children floating around me in the gloom, can never be told.

She gave birth to a baby girl a few weeks later, but the child did not survive.

From the flood museum website and the National Park Service.

For no reason, here’s a recipe for waffles that John Kennedy ate in the White House, “his breakfast treat for special occasions”:

1 tablespoon sugar

1/2 cup butter

2 egg yolks

1 cup and 1 tablespoon sifted cake flour

7/8 cup milk or 1 cup buttermilk

1/4 teaspoon salt

2 egg whites, stiffly beaten

4 teaspoons baking powderCream the sugar and butter. Add the egg yolks and beat. Then add the flour and milk alternately. This mixture may be kept in the refrigerator until you are ready to use it. When you are ready to bake it, fold in the egg whites, and add the baking powder and salt. Bake on a waffle iron. Serves 3.

“President Kennedy liked melted butter and maple syrup on his waffles.”

From White House chef François Rysavy’s 1972 collection A Treasury of White House Cooking.

Thomas Jefferson coined the word pedicure (at least in the sense “a person responsible for pedicure”).

His memorandum book for February 7, 1785, reads “P[ai]d La Forest, pedicure 12f.”

(Thanks, Joseph.)