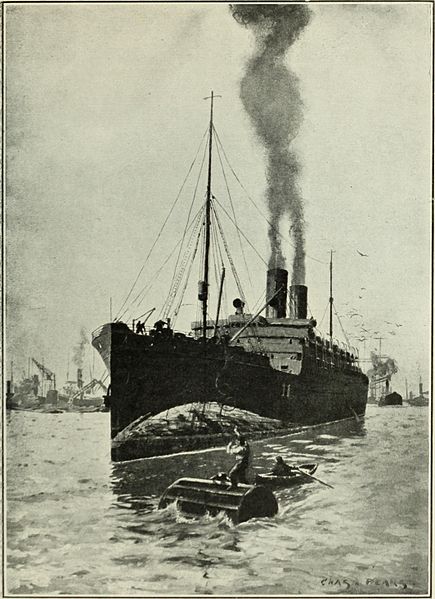

Following a series of shipwrecks in the 19th century, the government of New Zealand began to establish huts on remote subantarctic islands for the use of castaways, who otherwise might die of starvation or exposure.

The depots were stocked with firewood, rations, clothing, hunting and fishing equipment, medicine, and matches. Some included boat sheds, and steamers visited each island twice a year. To discourage opportunistic thieves, the government posted warnings on the provisions; one read, “The curse of the widow and fatherless light upon the man that breaks open this box, whilst he has a ship at his back.”

The project was discontinued after about 1927 as radio technology improved and the old clipper route fell out of use, but the depots were proving their value as late as 1908, when 22 crewmembers from the French barque President Félix Faure were shipwrecked in the Antipodes Islands. A depot there helped to sustain them until they could signal a passing warship.