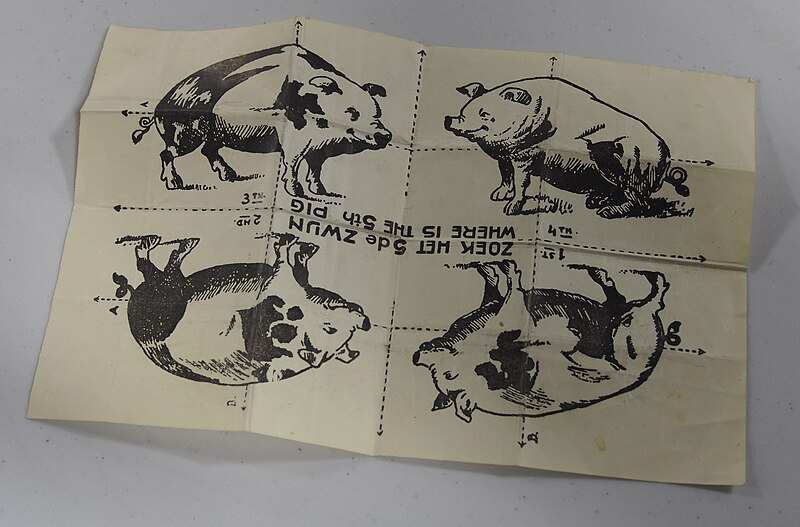

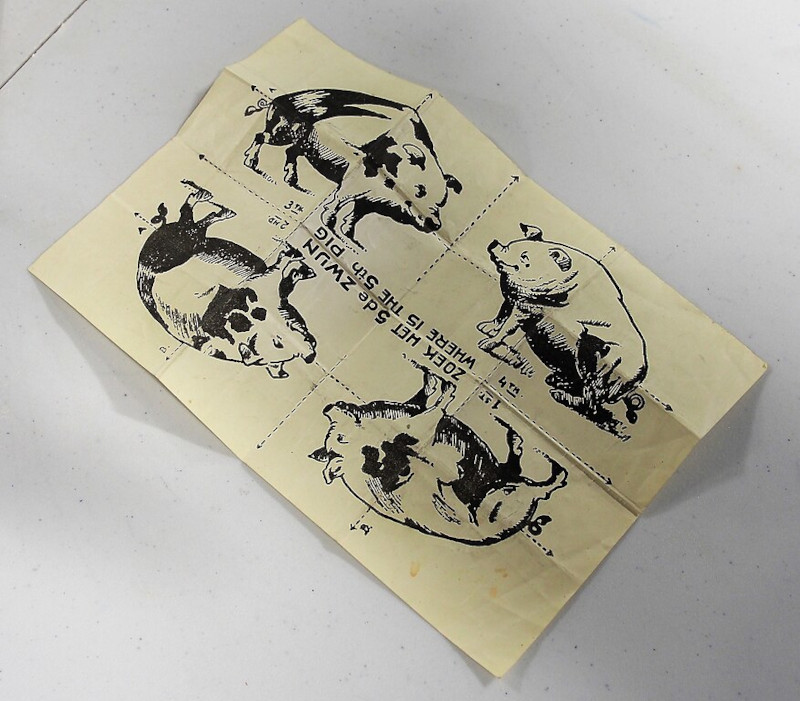

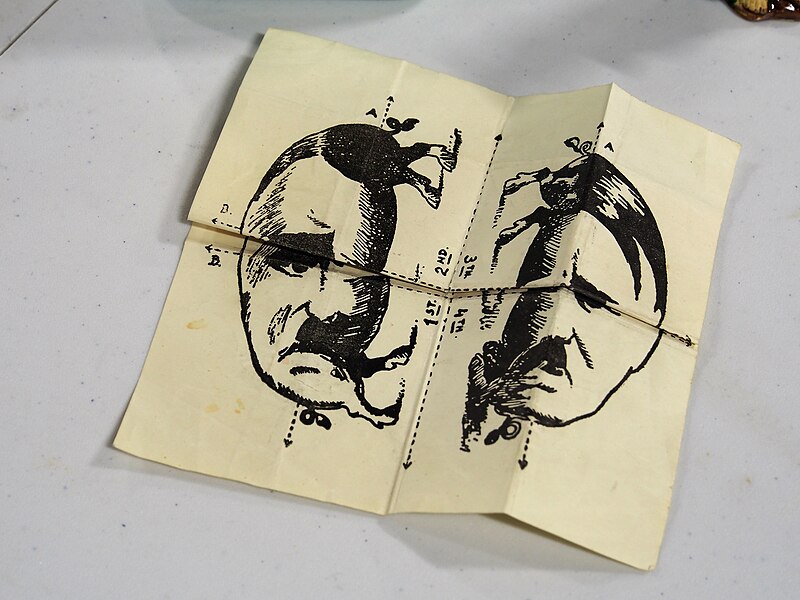

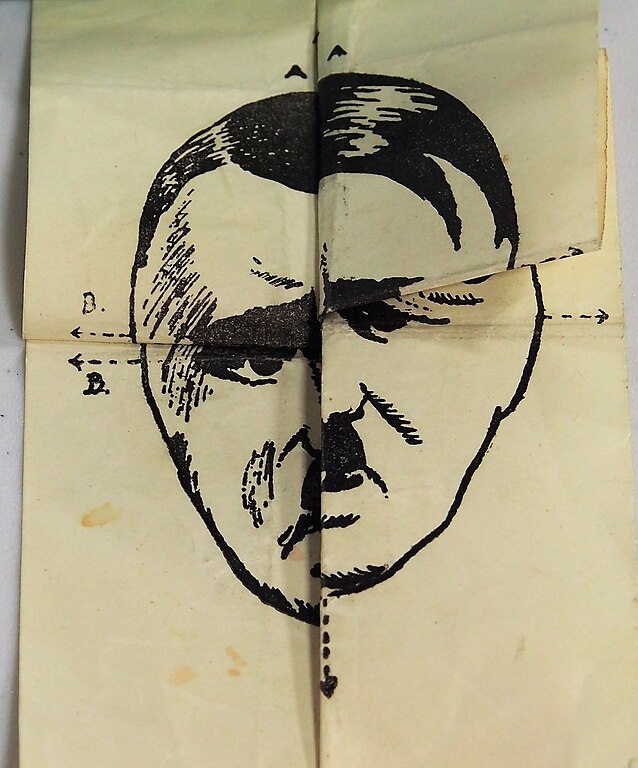

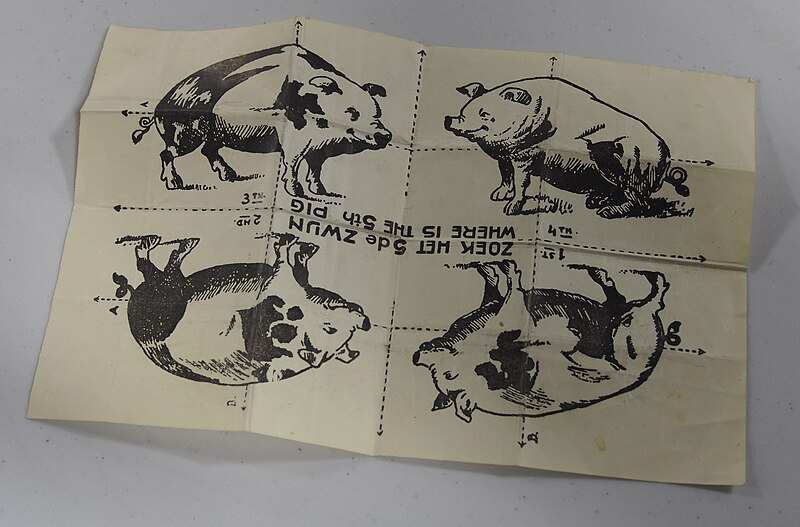

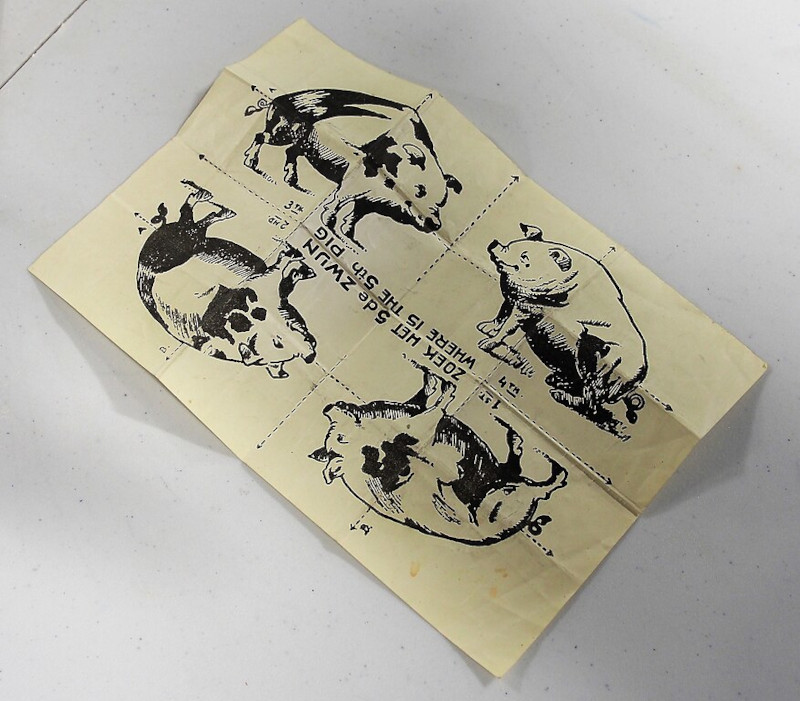

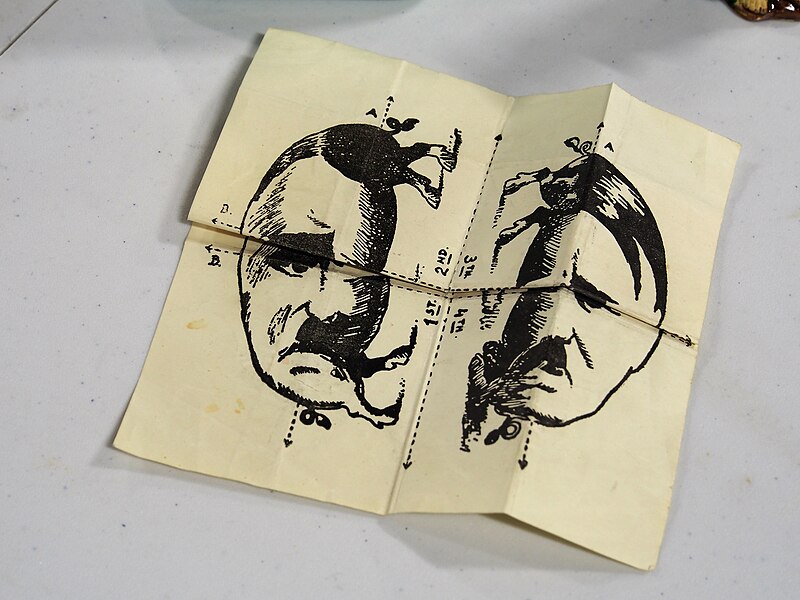

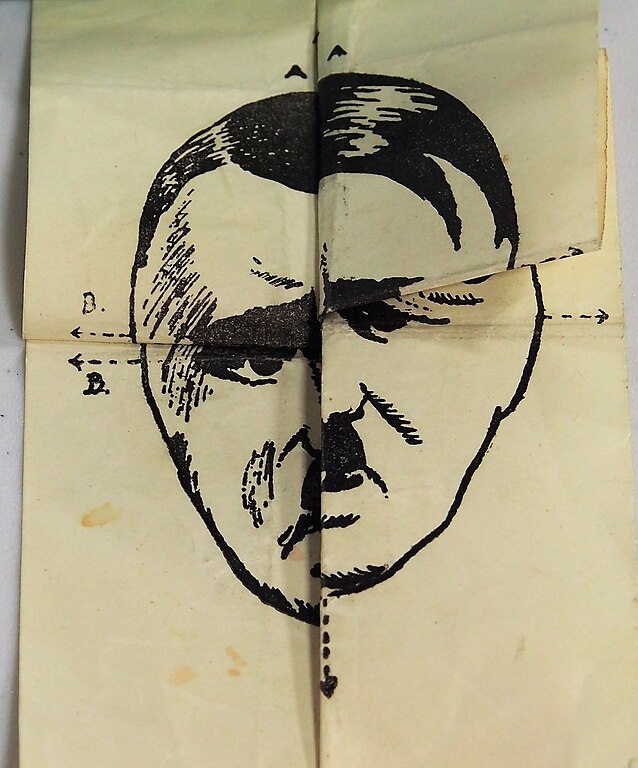

Just found this on Wikimedia Commons — “Where Is the Fifth Pig?”, an anonymous puzzle created in occupied Holland in 1940:

Just found this on Wikimedia Commons — “Where Is the Fifth Pig?”, an anonymous puzzle created in occupied Holland in 1940:

Under Roman law, subjects found guilty of patricide were subjected to poena cullei, the “penalty of the sack” — they were sewn into a leather sack with a snake, a cock, a monkey, and a dog and thrown into water.

In his Life of Artaxerxes, Plutarch describes an ancient Persian method of execution known as scaphism in which vermin devour a victim trapped between mated boats:

Taking two boats framed exactly to fit and answer each other, they lie down in one of them the malefactor that suffers, upon his back; then, covering it with the other, and so setting them together that the head, hands, and feet of him are left outside, and the rest of his body lies shut up within, then forcing him to ingest a mixture of milk and honey before pouring all over his face and body. They then keep his face continually turned towards the sun; and it becomes completely covered up and hidden by the multitude of flies that settle on it. And as within the boats he does what those that eat and drink must needs do, creeping things and vermin spring out of the corruption and rottenness of the excrement, and these entering into the bowels of him, his body is consumed.

Happily Plutarch seems to have based his account on a report by the Greek historian Ctesias, whose reliability has been questioned, so perhaps this never happened.

The village of Hensbroek in North Holland takes its name from the personal name Hein and the Dutch cognate of brook, i.e., “Henry’s brook.”

Magnificently, the municipal coat of arms interprets it instead as “hen’s breeches” — and depicts a chicken wearing trousers.

Ancient Athenians would sometimes encounter a remarkable sculpture on roads and in public places: The bearded head of the god Hermes set on a squared pillar of stone, with male genitals carved at the appropriate height. Hermes had been a phallic god before becoming a guardian of merchants and travelers, and so was associated with fertility, luck, roads, and borders. The hermae served as a form of protection from evil and were sometimes anointed with oil or bedecked with garlands.

Plato writes that “figures of Hermes” were set up “along the roads in the midst of the city and every district town” “with the design of educating those of the countryside,” sometimes by bearing edifying inscriptions. The sculptures did not always depict Hermes — this one, from the Athenian Agora, honors Demosthenes. The practice spread eventually to Rome, where the figures were known as mercuriae.

(Peter Keegan, Graffiti in Antiquity, 2014.)

calophantic

adj. pretending or making a show of excellence

velleity

n. a mere wish, unaccompanied by an effort to obtain it

fode

v. to lead on with delusive expectations

magnoperate

v. to magnify the greatness of

Roman diplomat Sidonius Apollinaris describes the hunting skill of Visigoth king Theodoric II:

If the chase is the order of the day, he joins it, but never carries his bow at his side, considering this derogatory to royal state. … He will ask you beforehand what you would like him to transfix; you choose, and he hits. If there is a miss … your vision will mostly be at fault, and not the archer’s skill.

(Quoted in Norman Davies, Vanished Kingdoms, 2012.)

Two thousand years ago, a Roman man pressed his hand into a brick that had been set out to dry before firing.

The brick is now held at the Archaeological Museum of Cherchell in Algeria.

From Reddit’s ArtefactPorn.

quisquous

adj. difficult to deal with or settle

quillet

n. a verbal nicety, a subtle distinction

aggiornamento

n. the act of bringing something up to date to meet current needs

irenic

adj. fitted or designed to promote peace

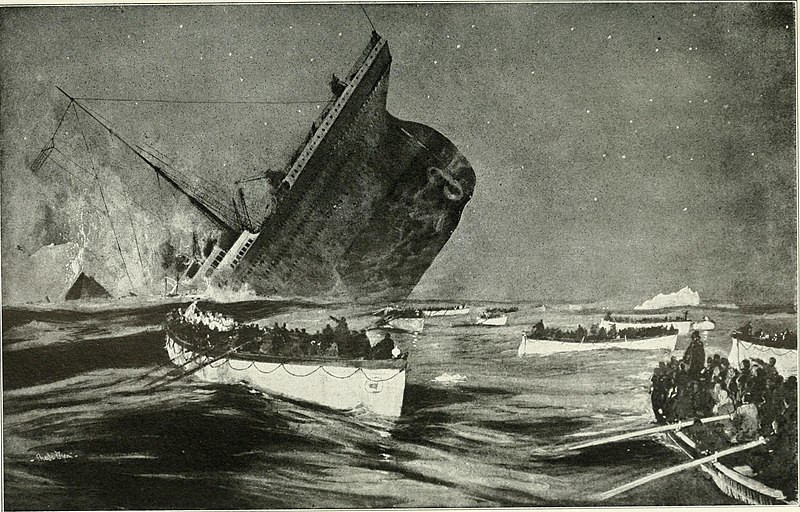

The survivors of the Titanic were picked up by the English passenger steamship Carpathia, which conveyed them to New York. This presented a delicate problem to the Social Register. “In those days the ship that people travelled on was an important yardstick in measuring their standing, and the Register dutifully kept track,” notes Walter Lord in A Night to Remember (1955). “To say that listed families crossed on the Titanic gave them their social due, but it wasn’t true. To say they arrived on the plodding Carpathia was true, but socially misleading. How to handle this dilemma? In the case of those lost, the Register dodged the problem — after their names it simply noted the words, ‘died at sea, 15 April 1912’. In the case of those living, the Register carefully ran the phrase, ‘Arrived Titan-Carpath, 18 April 1912’. The hyphen represented history’s greatest sea disaster.”

Imprisoned at Theresienstadt during World War II, Czech composer Rudolf Karel wrote a five-act opera, Three Hairs of the Wise Old Man, on toilet paper using the medicinal charcoal he’d been prescribed for his dysentery.

The illness eventually claimed his life, but a sketch of the opera was preserved by a friendly warden, and the orchestrations were finished by Karel’s pupil Zbynek Vostrák.

manqueller

n. a man killer; an executioner

In 1014, after a decisive victory over the Bulgarian Empire at the Battle of Kleidion, Byzantine emperor Basil II followed up with a singularly cruel stroke. He ordered that his 14,000 prisoners be divided into groups of 100; that 99 of each group be blinded; and that the hundredth retain one eye so that he could lead the others home. The columns were then released into the mountains, each man holding on to the belt of the man in front. It’s not known how many were lost on the journey, but when the survivors reached the Bulgar capital, their tsar collapsed at the sight and died of a stroke two days later. Basil is remembered as “the Bulgar slayer.”

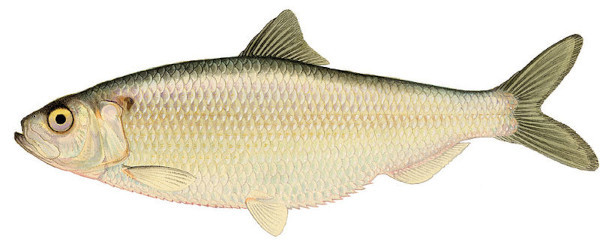

Early European colonists were staggered at the abundance of fish in the Chesapeake Bay. William Byrd II wrote in his natural history of Virginia:

Herring are not as large as the European ones, but better and more delicious. When they spawn, all streams and waters are completely filled with them, and one might believe, when he sees such terrible amounts of them, that there was as great a supply of herring as there is water. In a word, it is unbelievable, indeed, indescribable, as also incomprehensible, what quantity is found there. One must behold oneself.

More accounts here. “The abundance of oysters is incredible,” marveled Swiss explorer Francis Louis Michel in 1701. “There are whole banks of them so that the ships must avoid them. A sloop, which was to land us at Kingscreek, struck an oyster bed, where we had to wait about two hours for the tide.”