Higgledy-piggledy,

Benjamin Harrison

Twenty-third president

Was and, as such,

Served between Clevelands and,

Save for this trivial

Idiosyncrasy,

Didn’t do much.

— John Hollander

Higgledy-piggledy,

Benjamin Harrison

Twenty-third president

Was and, as such,

Served between Clevelands and,

Save for this trivial

Idiosyncrasy,

Didn’t do much.

— John Hollander

In 1905 Winchester Cathedral was in danger of collapsing as its eastern end sank into marshy ground. The surprising solution was to hire a diver, who worked underwater for five years to build a firmer foundation for the medieval structure. In this week’s episode of the Futility Closet podcast we’ll tell the story of William Walker and his curious contribution to saving a British landmark.

We’ll also contemplate a misplaced fire captain and puzzle over a shackled woman.

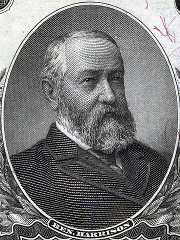

This test was administered to recruits at Fort Devens, Mass., during World War I. The idea is to measure reading comprehension, but the questions take on a surreal poetry:

Norms:

Below 6: Illiterate

6 to 20: Primary

21 to 25: Grammar

26 to 30: Junior high school

31 to 35: Senior high school

36 to 42: College

Three additional versions of the test are given here.

The world’s longest airplane flight took place in 1958, when two aircraft mechanics spent 64 days above the southwestern U.S. in a tiny Cessna with no amenities. In this week’s episode of the Futility Closet podcast we’ll follow the aerial adventures of Bob Timm and John Cook as they set a record that still stands today.

We’ll also consider a derelict kitty and puzzle over a movie set’s fashion dictates.

(Thanks, Tony.)

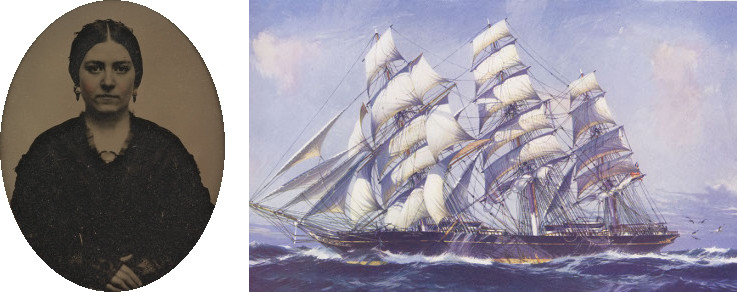

In 1856, an American clipper ship was approaching Cape Horn when its captain collapsed, leaving his 19-year-old wife to navigate the vessel through one of the deadliest sea passages in the world. In this week’s episode of the Futility Closet podcast we’ll tell the story of Mary Patten and the harrowing voyage of the Neptune’s Car.

We’ll also consider some improbable recipes and puzzle over a worker’s demise.

In his 1874 Lives of the Chief Justices of England, John Campbell tells this anecdote of Lloyd Kenyon, Chief Justice of England and Wales from 1788 to 1802:

In those days retiring-rooms for the use of the Judges were unknown, and a porcelain vase, with a handle to it, was placed in a corner of the Court at the extremity of the bench. In the King’s Bench at Guildhall the students’ box (in which I myself have often sat) was very near this corner. One day a student who was taking notes, finding the ink in his little ink-bottle very thick, used the freedom secretly to discharge the whole of it into my Lord’s porcelain vase. His Lordship soon after having occasion to come to this corner, he was observed in the course of a few moments to become much disconcerted and distressed. In truth, discovering the liquid with which he was filling the vase to be of a jet black colour, he thought the secretion indicated the sudden attack of some mortal disorder. In great confusion and anguish of mind he returned to his seat and attempted to resume the trial of the cause, but finding his hand to shake so much that he could not write, he said that on account of indisposition he was obliged to adjourn the Court.

Happily for Kenyon, “As he was led to his carriage by his servants, the luckless student came up and said to him, ‘My Lord, I hope your Lordship will excuse me, as I suspect that I am unfortunately the cause of your Lordship’s apprehensions.’ He then described what he had done, expressing deep contrition for his thoughtlessness and impertinence, and saying that he considered it his duty to relieve his Lordship’s mind by this confession. Lord Kenyon: ‘Sir, you are a man of sense and a gentleman — dine with me on Sunday.'”

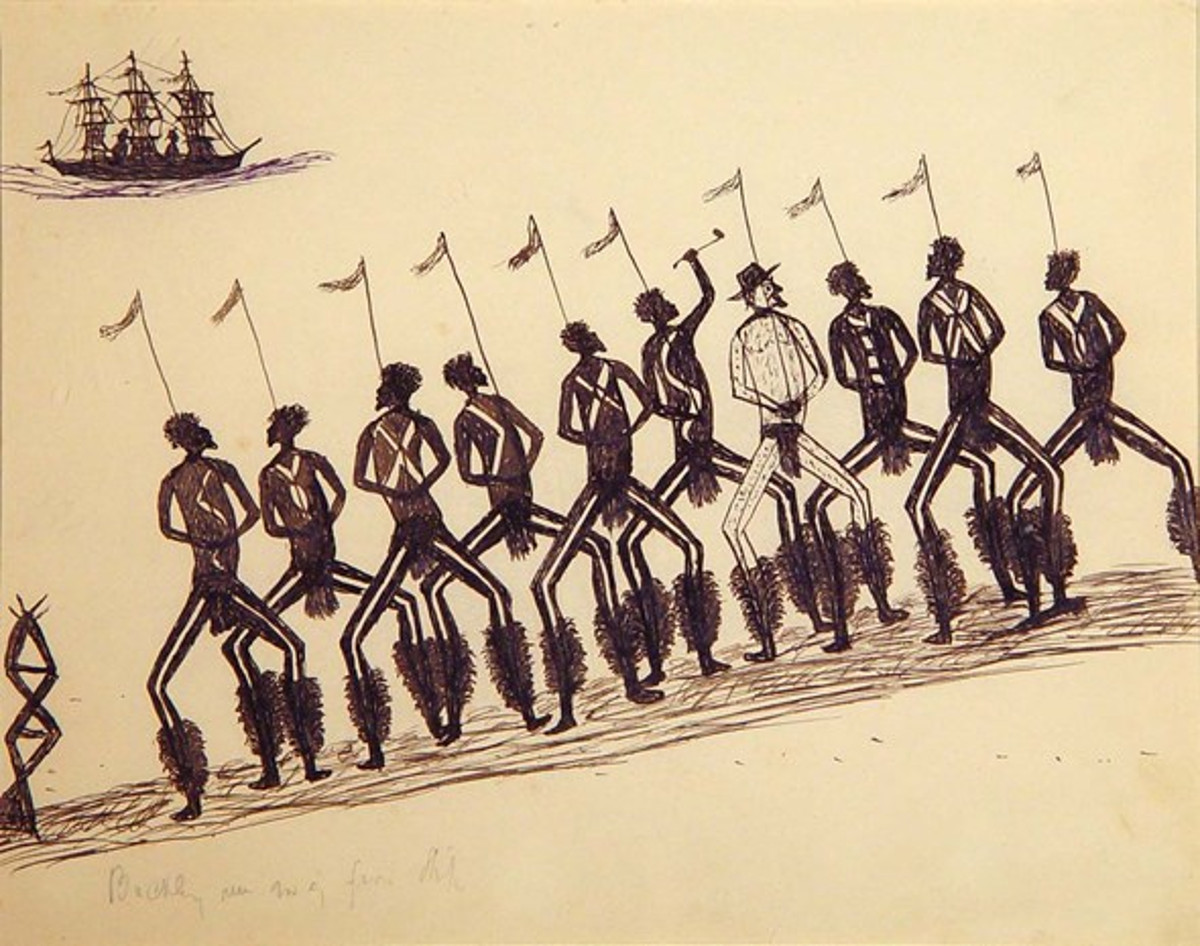

In 1835, settlers in Australia discovered a European man dressed in kangaroo skins, a convict who had escaped an earlier settlement and spent 32 years living among the natives of southern Victoria. In this week’s episode of the Futility Closet podcast we’ll review the extraordinary life of William Buckley, the so-called “wild white man” of colonial Australia.

We’ll also try to fend off scurvy and puzzle over some colorful letters.

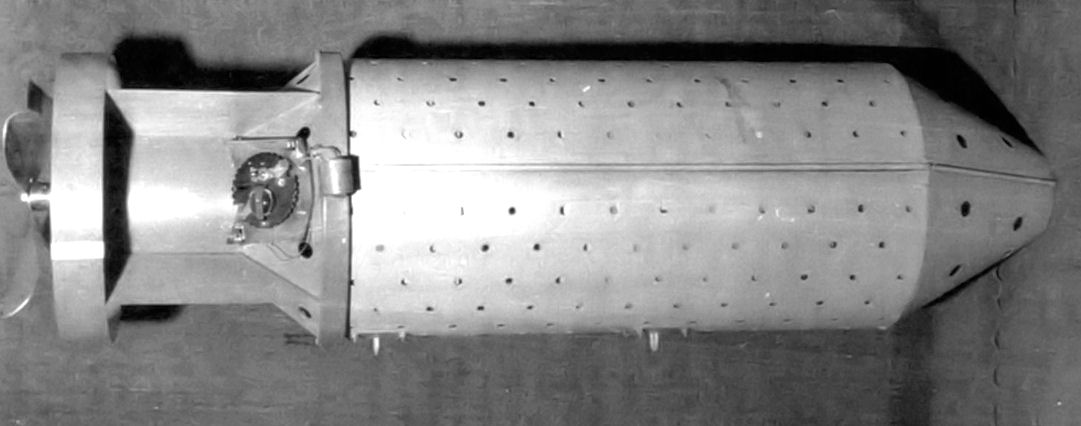

During World War II, the U.S. Army experimented with a bizarre plan: using live bats to firebomb Japanese cities. In this week’s episode of the Futility Closet podcast we’ll describe the crazy history of the bat bomb, the extraordinary brainchild of a Pennsylvania dentist.

We’ll also consider the malleable nature of mental illness and puzzle over an expensive quiz question.

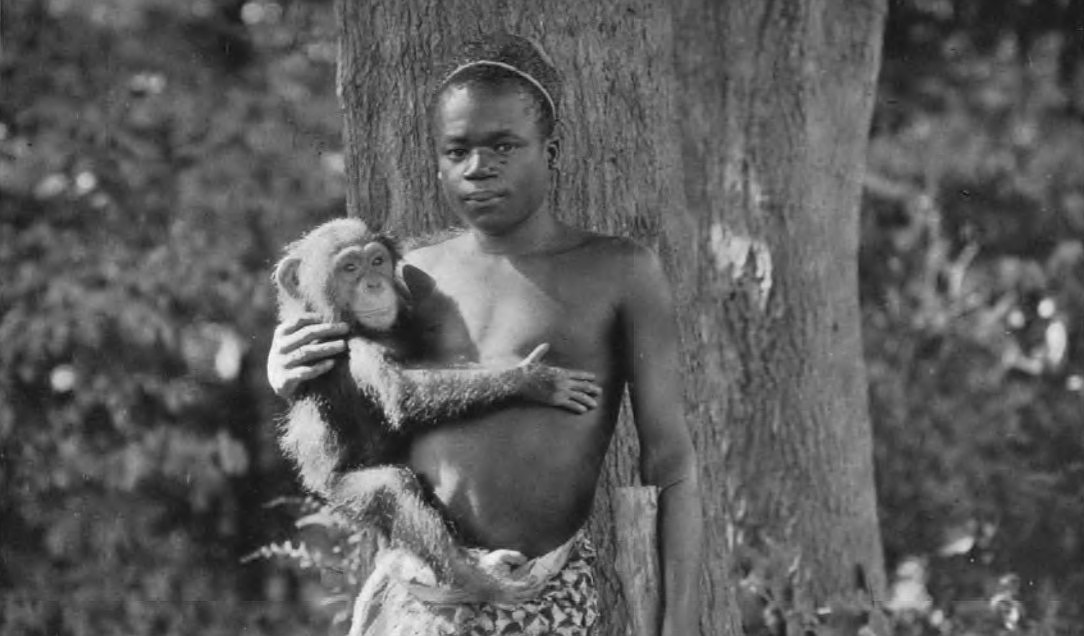

The Bronx Zoo unveiled a controversial exhibit in 1906 — a Congolese man in a cage in the primate house. The display attracted jeering crowds to the park, but for the man himself it was only the latest in a string of indignities. In this week’s episode of the Futility Closet podcast we’ll review the sad tale of Ota Benga and his life in early 20th-century America.

We’ll also delve into fugue states and puzzle over a second interstate speeder.