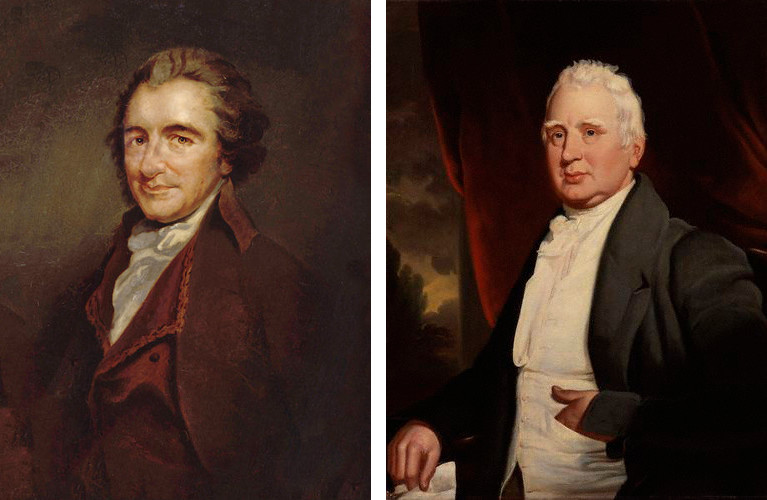

Thomas Paine came to an ignominious end. The revolutionary activist so inspired English journalist William Cobbett that Cobbett dug up his bones in 1819 and transported them back to England, hoping to give Paine a heroic reburial in the land of his birth. (G.K. Chesterton wrote, “I wonder what he said when asked if he had anything to declare?”)

But Cobbett never got around to it. When he himself died in 1835, Paine’s bones were still among his effects, and they’ve since been lost: His skull may be in Australia, his jawbone may be in Brighton, or maybe Cobbett’s son buried everything in the family plot when he couldn’t auction it off. In 1905 part of his brain (“resembling hard putty”) may have been buried under a monument in New Rochelle, N.Y. But no one knows for sure.