Is it unjust to adopt a constitution that binds both ourselves and future members of our society? We need a set of fundamental laws to regulate ourselves, but is it fair to extend that to future citizens? Shouldn’t they have the right to choose their own rules?

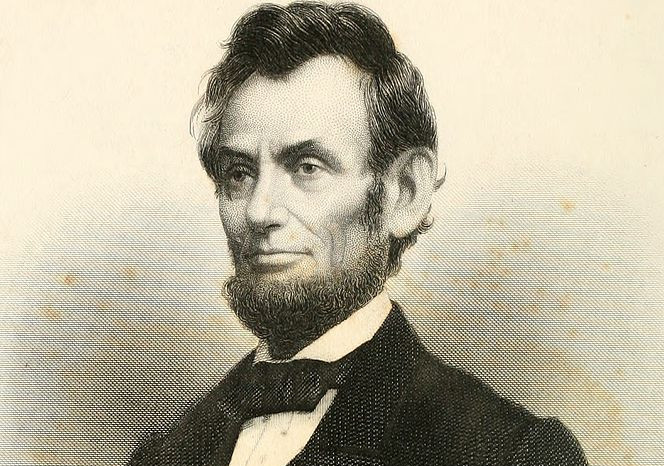

Thomas Jefferson thought so. In a 1789 letter to James Madison, he held that “the earth belongs in usufruct to the living”: He thought a constitution (or any law) should expire automatically when succeeding generations make up a majority of the population. “The constitution and the laws of their predecessors extinguished … in their natural course with those who gave them being,” he wrote. “This could preserve that being till it ceased to be itself, and no longer. … If it be enforced longer, it is an act of force, and not of right.”

There’s a tension here: In order for a constitution to be successful, it has to define the organization of its society and the freedoms of its citizens, and these rules need to remain in effect for at least several generations in order to produce a healthy liberal democracy. “But those born under a perpetual constitution are expected to acquiesce to the foundational norms approved by their predecessors with neither their consent nor their participation,” writes McGill University political philosopher Víctor M. Muñiz-Fraticelli. “If a constitution is discussed, negotiated, and approved by citizens who are, necessarily, contemporaries, what normatively binding force does it retain for future generations who took no part in its discussion, negotiation, or approval?”

(Víctor M. Muñiz-Fraticelli, “The Problem of a Perpetual Constitution,” in Axel Gosseries and Lukas H. Meyer, eds., Intergenerational Justice, 2009.)